“Like most salesmen, he gave his best self to his prospective customers, and saved his rage, sarcasm, and indifference for his family.”—John Updike, Bech at Bay

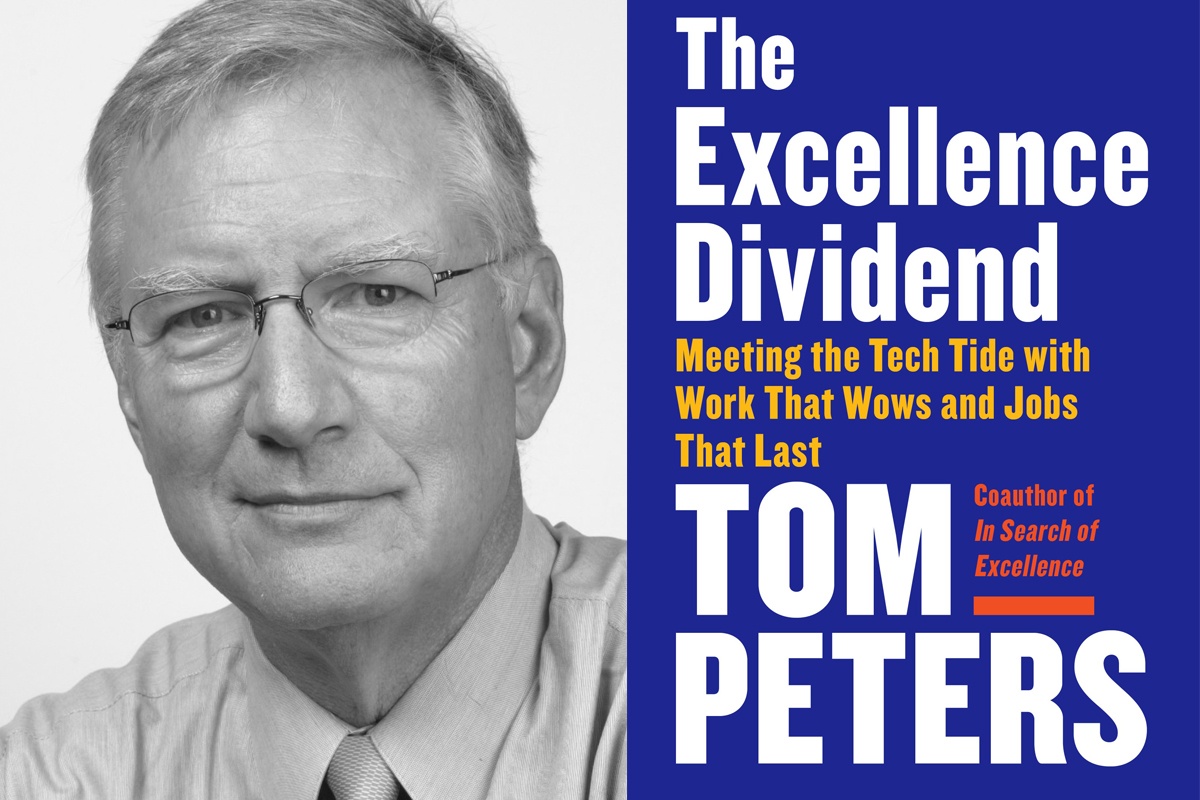

When Aristotle says: “The excellent becomes the permanent,” he is referring to the long-term ethical health of humanity. The generation-spanning ripples of canonical learning. When Tom Peters, best-selling business author, human exclamation point, and incessant Twitter conversationalist, pronounces the word “excellence,” he’s talking about a real-time ethical imperative. He suggests that putting one’s whole being into one’s work will make the difference—in a career, to a company, for the economy—and that opting out of excellence will cost you.

Peters is chiefly concerned with (a) the impact automation will have on employees; and (b) how excellence, in its myriad forms (personal, professional, managerial, ethical) can resist, at least temporarily, automation’s impact. In a recent phone conversation about excellence, Peters proved to be intelligent and open-minded regarding its significant power and price.

“We’ve gotta provide excellence in the services that we are delivering,” Peters told me in a phone interview. “You gotta deliver excellence to every damned one of your clients today.” It’s about putting people first, paying attention to details of your design projects, pushing to make the people you serve, all the people in your ecosystem, feel attended to. This excellence resembles Robert Pirsig’s notion of “quality”—it’s difficult to define but you know it immediately when you see it embodied in a person, product or service design.

It’s easy enough to admire excellence—though there are many people who feel that their professional lives are its polar opposite. According to Gallup, only 32% percent of U.S. workers are engaged. And yet, mediocrity is not a banner anyone wishes to march under. It may be that the gap between unrealized, aspirational excellence and the mediocre reality might be a reason for Peters’ enduring success as a writer and speaker.

One of the most appealing things about The Excellence Dividend is that it seems less a business tome than a lyrical poem to human potential. It is, in a way, a heavily annotated commonplace book, filled with resonant quotes and his own authentic in-the-moment responses, designed to inspire the reader and himself. The Excellence Dividend is not proving a point—it would be hard to show data proving that excellence can take automation in ten rounds—but rather about getting some inspiring feeling out there. And such a feeling is most welcome when dealing with, say, the fifth set of revisions that your most attention-grabbing client has demanded of you.

“Unless you were born with a silver spoon, the practical fact is, that you will be spending more of your adult waking hours at your job than you will even with your family,” he says, “And so if you piss away those hours, you have...pissed away your life.”

Which brings us to the shadow that The Excellence Dividend, from a certain angle, casts. An unremitting pursuit of excellence could well ferment into workaholism, one surely familiar to detail-obsessed designers. I recently bumped into an article called “More College Students Seem to Be Majoring in Perfectionism” and wondered if creating a workforce purely on excellence, and consequently without any kind of work-life balance, might cause problems in the long run.

It might be difficult to sustain a life of focused, professional excellence and have, say, an equally excellent (which is to say, happy) personal life. The question of how and when to put one’s best self out into the world sits at the heart of excellence, and the precise answer to this cannot be found in Peters’ new book, or anywhere else. There is some recent research that seeks to differentiate between “workaholism” and “working long hours”—the idea is that compulsive work mindset, not necessarily long hours, leads to health problems—but it seems obvious that committing absolutely to work will interfere with the non-work elements in one’s life.

Which is to say, designers: while your prospects and clients do need your very best, so does your spouse, your children, your community, your country. Can you give your all to all these competing interests? The answer is: unlikely. It’s your attitude toward that “unlikely” that makes the difference in evaluating your own sense of life’s successes or failures.

Peters says that people asked him, while composing The Excellence Dividend, “Why don’t you write a memoir?” his response was: “No, I can’t because I have no desire whatsoever to publicly air some of the collateral damage in things like relationships that were caused by spending 200 days on the road giving speeches.”

You hear this and think: that's an honest guy! He admits, even if obliquely, that his own professional drive had taken a toll on his personal life. One thinks of the pain Peters, and every other A+-type business person, has caused and suffered while chasing after excellence. William Blake understood the economics of experience well:

What is the price of Experience? Do men buy it for a song?

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No, it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath, his house, his wife, his children .

It's doubtful that success will be found equally in all endeavors. And that’s OK. Perhaps the lesson we can take from Peters is to define those areas in which we want to succeed and the terms of our success. If success is about earning a certain amount of money, track closely how you are approaching, or veering away from, your monetary goal. If it’s about doing cooler design projects, then perhaps you need to find a way to lose the boring accounts and find a way to do more work that moves you. And if success is spending more time with your partner or kids, make sure you find sufficient time with them. Not to get too prescriptive here (Peters says: “I have a real problem with the how-to books on how to make yourself a better person”), but maybe the first step towards excellence is forcing ourselves to be as conscious as we are realistic about our ambitions.