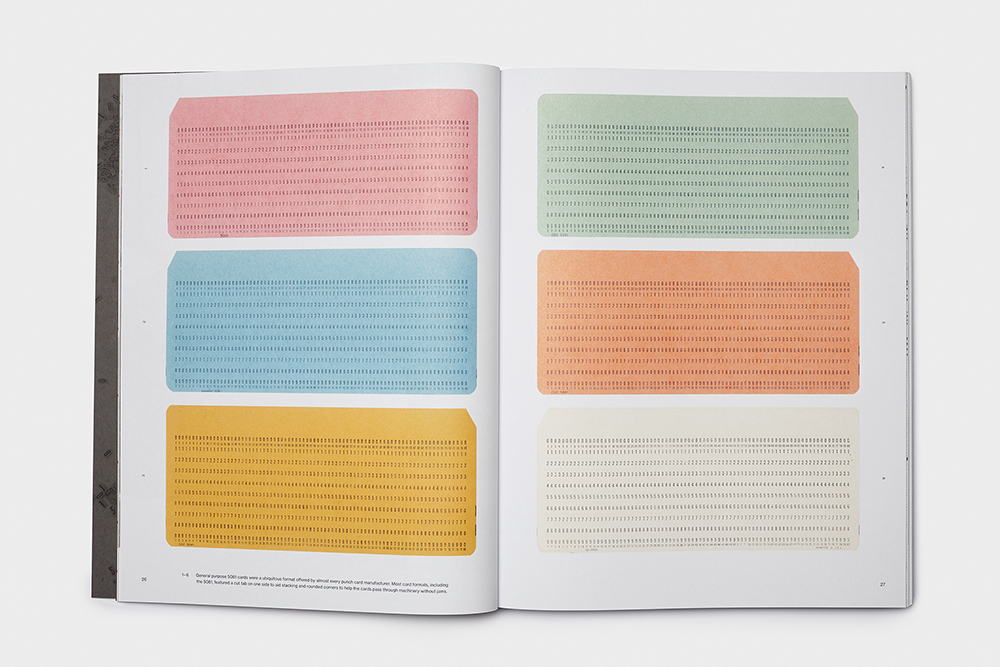

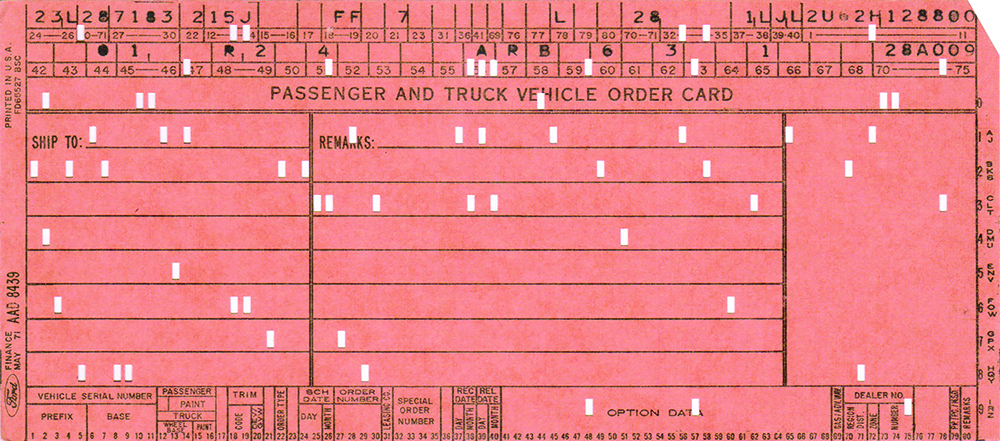

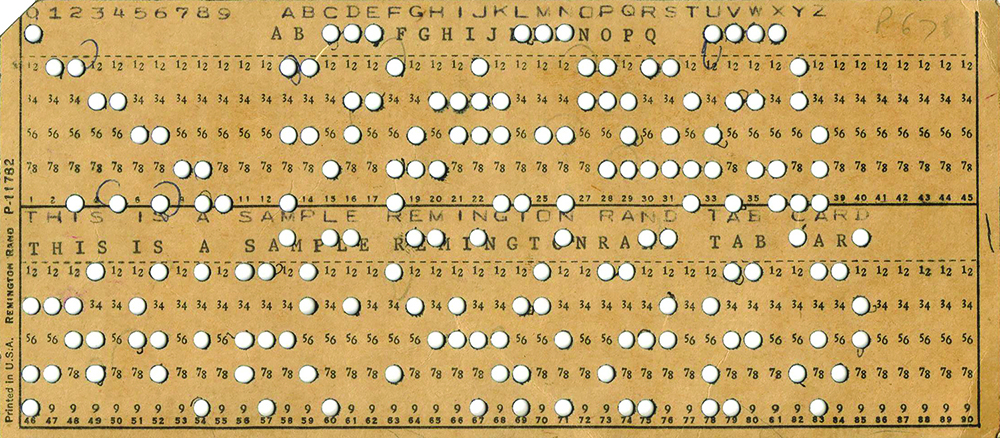

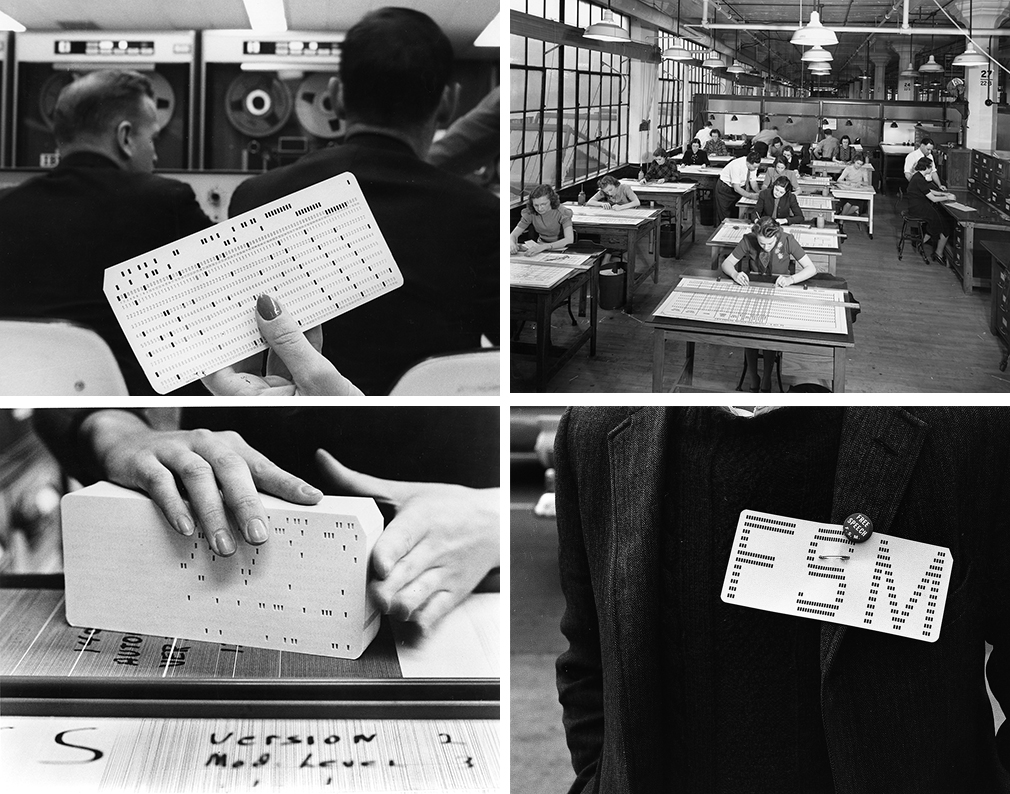

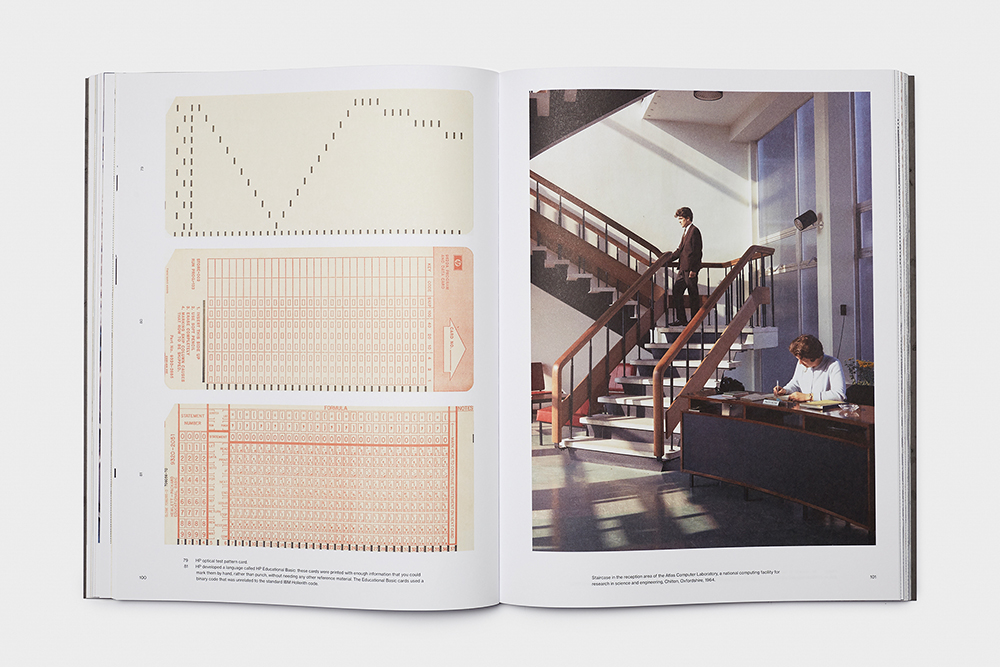

Data used to be physical. In an era when 1s and 0s seem to hover above our heads, the new book Print Punch returns to the heyday of the punch card — to a time when you could touch (and punch) data. The aesthetics of this early move towards automation represent a unique moment in our history, when we designed for machines instead of human beings. Rigorous constraints, inherent in punch card technology, unwittingly birthed a coherent design language: rhythm in grids, punched absences and presences, and the patterns in them dancing to their own machine logic. Now obsolete, punch cards were the primary method of data storage and processing from the 1890s until the late 1970s; spanning almost a century of ubiquitous utility, the artefacts of that era sit between these pages to be examined anew.

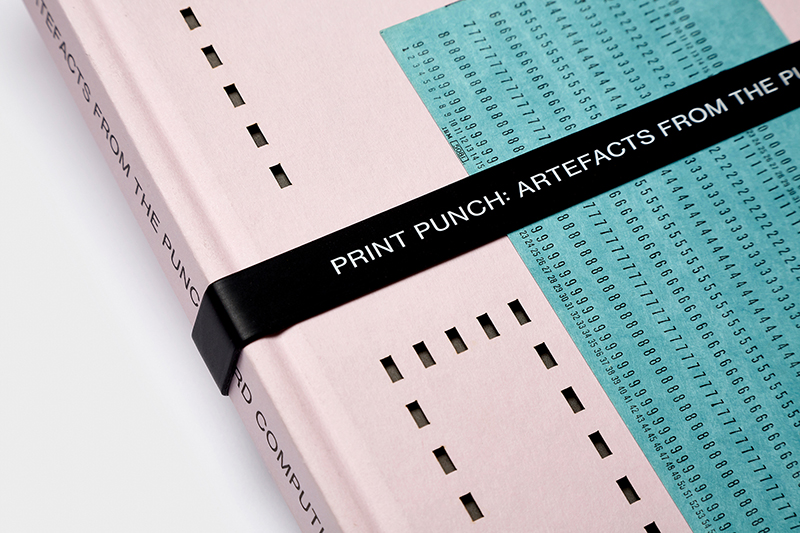

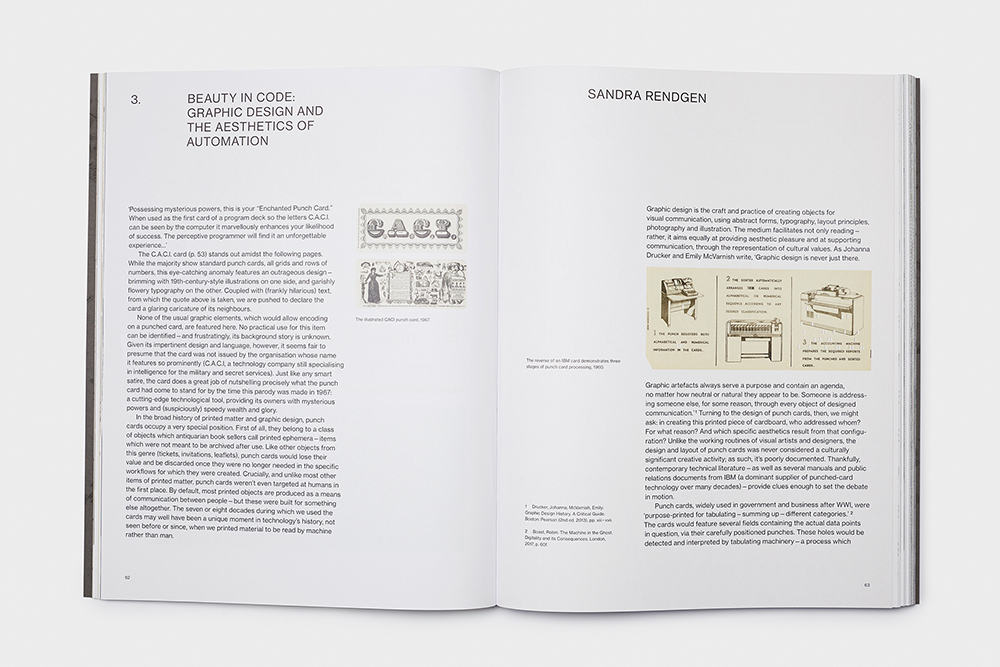

The laser-cut case-bound 208 page book contains over 220 punch cards and 150 largely unseen archival images. The book features an introduction from John L. Walters, design journalist and editor of Eye magazine. An essay from Sandra Rendgen, a writer with a focus on information graphics, interactive media, and the history of information visualisation and author of The History of Information Graphics (2019). And and a third text from Steven E. Jones, Professor of Digital Humanities, University of South Floridaand author of Roberto Busa, S. J., and the Emergence of Humanities Computing: The Priest and the Punched Cards (2016).

Designed and edited by Patrick Fry, Print Punch is a collection of designed objects that were created by engineers and technicians rather than designers, they were designed primarily to be read by computers and secondly by humans. This gives them a unique quality and a tension between form and function. As such they are a great example of CentreCentre’s goal to highlight overlooked chapters of art and design history. The following excerpt and images are published here with permission of the editor.

From ‘Beauty in Code: Graphic design and the aesthetics of automation’ by Sandra Rendgen

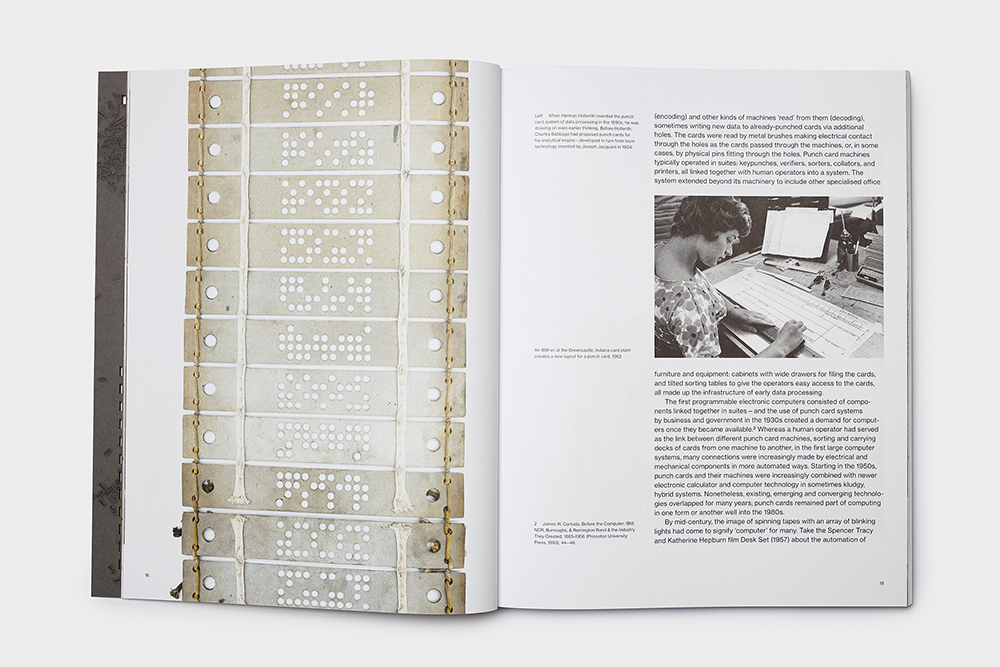

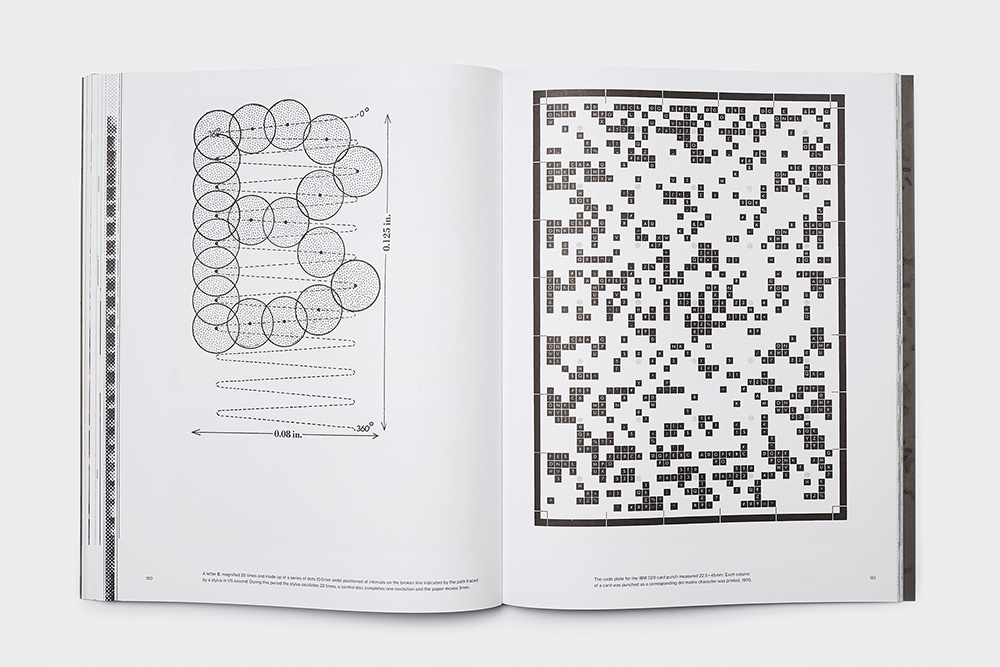

In the broad history of printed matter and graphic design, punch cards occupy a very special position. First of all, they belong to a class of objects which antiquarian book sellers call printed ephemera—items which were not meant to be archived after use. Like other objects from this genre (tickets, invitations, leaflets), punch cards would lose their value and be discarded once they were no longer needed in the specific workflows for which they were created. Crucially, and unlike most other items of printed matter, punch cards weren’t even targeted at humans in the first place. By default, most printed objects are produced as a means of communication between people—but these were built for something else altogether. The seven or eight decades during which we used the cards may well have been a unique moment in technology’s history, not seen before or since, when we printed material to be read by machine rather than man.

Graphic design is the craft and practice of creating objects for visual communication, using abstract forms, typography, layout principles, photography and illustration. The medium facilitates not only reading—rather, it aims equally at providing aesthetic pleasure and at supporting communication, through the representation of cultural values. As Johanna Drucker and Emily McVarnish write, ‘Graphic design is never just there. Graphic artefacts always serve a purpose and contain an agenda, no matter how neutral or natural they appear to be. Someone is addressing someone else, for some reason, through every object of designed communication.’ Turning to the design of punch cards, then, we might ask: in creating this printed piece of cardboard, who addressed whom? For what reason? And which specific aesthetics result from that configuration? Unlike the working routines of visual artists and designers, the design and layout of punch cards was never considered a culturally significant creative activity; as such, it’s poorly documented. Thankfully, contemporary technical literature—as well as several manuals and public relations documents from IBM (a dominant supplier of punched-card technology over many decades)—provide clues enough to set the debate in motion.

Patrick Fry founded CentreCentre in 2018.