Enomoto Chikatoshi, Young Woman Adjusting Her Skis, late 1930s. All images courtesy Levenson Collection.

A dancer in a liquid, backless dress stares at herself in a horizontal mirror, feet resting on a black square of a checkerboard floor. Also reflected in the mirror: the curving tubular steel of a cantilever chair, its seat daringly upholstered in a tiger stripe. Where are we? The woman, possibly weeping, could be Dietrich. The furniture, possibly a knock-off, could be Breuer, But we're a long way from the Bauhaus. It's a photograph by Hamaya Hiroshi from 1935, taken at Tokyo's Ballroom Florida dancehall. In one image there's Hollywood glamor, modernist furniture, the dawn of photojournalism and some out-of-context American tourism (“Florida” was, in fact, copied from a Parisian dancehall of that name).

Hamaya Hiroshi, Dancer Looking Herself in a Mirror, Ballroom Florida, Akasaka, Tokyo, 1935.

This photograph, part of the Japan Society's new exhibition "Deco Japan: Shaping Art and Culture, 1920-1945" is a prime example of the surprising globalism of this little-known period in Japanese design, when pent-up post-1923-earthquake desires for new goods and new traditions met up with a new openness to Western arts and the rise of industrialization. And women played a prominent role. Guest curator Kendall H. Brown told Salon:

Thematically, the aspect of Japanese deco of the ’20s and ’30s that epitomizes this cosmopolitan urban culture is the subject of the “modern girl,” who is in some ways sort of the “flapper.” This kind of middle- to upper-middle-class urban woman wears Western clothes — and even if she wears a kimono, she might have a Western hairstyle and accessories. She goes window-shopping. She goes to cafes. She smokes. She drinks. She ostentatiously does her makeup, in a pocket mirror. The modern girl is perhaps the crucible of the deco culture.

There are unmistakable parallels between the experience of women and consumer culture in the USA and Japan between the wars, entering the workforce, moving to cities, and having the buying power to outfit their homes to their modern taste.

The Ballroom Florida was part of a nightclub boom in the late 1920s, and able to charge a premium. A postcard in the exhibition of the Takarazuka Kaikan “dancing hall”, located in the suburbs between Osaka and Kobe and designed by Furuzuka Masaharu, shows a streamline building with white stucco walls and black stripes, its name spelled out on a vertical sign notched like a Frank Lloyd Wright hollyhock. A set of wall-size fan-shaped paintings by Enomoto Chikatoshi show Florida dancers as, and with, their accessories: jade clutches, elbow-length gloves, Scarlett O’Hara ruffles. They lean seductively against more tubular steel railings. Only their faces look Japanese.

Enomoto Chikatoshi, Florida (Furorida), 1935.

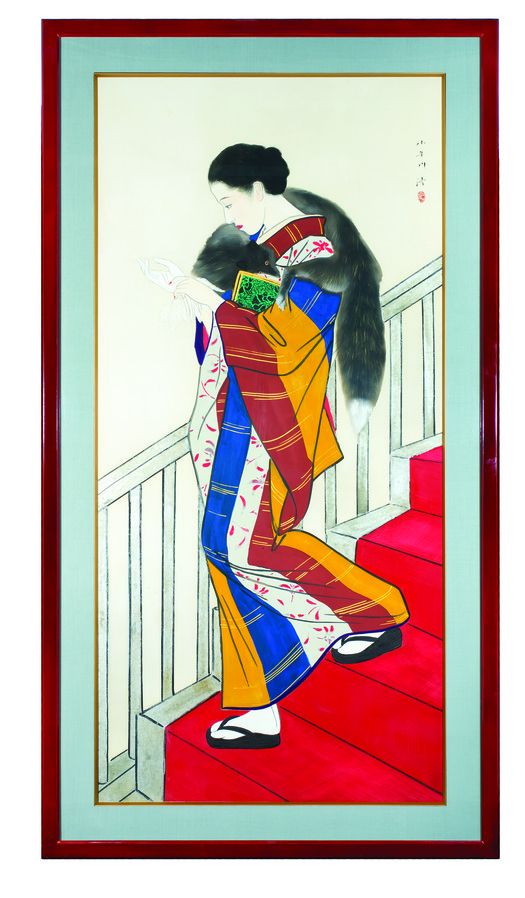

But the modern woman, or moga, wasn’t only a dancehall girl. Other works in the exhibit show her skiing (check those reindeer gloves), smoking, or more tentatively moving between tradition and modernity. I particularly liked Kobayakawa Kiyoshi’s large drawing “Staircase (Kaidan)” which represented December in traditional pictures of the months cycle. The subject is a young women walking down a staircase, wearing a fashionable boldly-striped kimono and black geta. But around her shoulders is a fox stole, tucked under her arm is a malachite clutch, and she’s putting on lace-trimmed white gloves. The painting reminds me of a 19th century fashion plate, or a Vogue editorial on accessories. Her body and pose seem awkwardly arranged to show off all the elements of contemporary style. (An aside, this looks like a gorgeous book on Deco kimono, several of which are on display in this exhibition. I particularly liked one patterned with movie posters, including “King of Kings” and “Shochikuza” and lots of bare feminine legs.)

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi, Kaidan (Staircase); December, from series Jūnikagetsu tsukinamie (Pictures of the Months), 1935.

In a nearby case, a few of those stylish accessories are on display: a whirlpool design obi clip on a striped silk ribbon, and a black comb and compact ornamented with silver triangles. While the obi clip is only-in-Japan, these accessories could have been sold in New York, and would be a close match for the black lacquer designers like Donald Deskey adapted from the Japanese.

The other role for the modern woman was at home. Japan entered its own period of suburbanization during the 1920s and 1930s, and upper class women outfitted their “culture homes” with both Japanese and Western rooms, accessorized with small Deco objects. The catalog mentions Noritake as a multi-national firm, with a design office in New York and manufacturing in Japan, which sold objects in both countries. A culture home might have a portrait of its mistress with a Christmas tree. She might send out a Happy New Year postcard with a streamlined automobile. She might drink her tea from a blue-and-white Noritake cup with a handle, striped in silver. Or instead, serve sake from an Akita flask faceted to look like crystal. Brown writes, “the class-conscious young woman was an arbiter of domestic taste, and her desire for status was a critical factor in choosing objects.”

Kosen, Sake Flask in the Form of an Akita Dog, 1930s.

The exhibition isn’t perfect. It is small, and there could be much more discussion of the intersection of craft and industrialization. (The New York Times review is here; Ken Johnson provides a good survey of the show and some of the darker nationalist aspects of Deco.) I might have preferred more abstraction, fewer animals. But it is based on the pioneering private collection of Robert and Mary Levenson, with a few key loans, and it seems to open up many possibilities for future scholarship and Deco shows across national lines. As a non-expert, I would have liked to see more stylistic comparison. What’s the difference between a traditional bull, a Deco bull, and a modernist bull? And how did the French or the Americans do lacquerware during the same period? But I keep returning to the international mysteries of that photograph, and thinking about how those materials, that dress, those chairs made it into a Tokyo nightclub, and it makes me excited about the cultural intrepidness of design ideas.