Still from The Sarany Motel, a film by Elliott Earls, 2007

This fall, Elliott Earls, head of the 2-D Design Department at Cranbrook Academy of Art, will release his second feature-length film The Sarany Motel, which he produced, directed, stars in, composed the music for, and edited. Through his diverse body of work Earls has pushed the boundaries of design authorship perhaps more than any other graphic designer, but the field has changed a great deal since he released Throwing Apples at the Sun, his first major foray into film/music/design hybrid over a decade ago. The release of The Sarany Motel comes amidst a flood of self-published books, podcasts, zines, and blogs by designers. It no longer seems quite as audacious for a designer to make a movie. Instead it raises questions like: Has the dominance of the "designer as author" model transformed graphic design into a vague form of cultural production?; and, Is the allure of the legitimacy of authorship pulling design away from the defining characteristic of the profession — the designer/client relationship?

Trailer for The Sarany Motel, a film by Elliott Earls, 2007

Notions of authorship have percolated in graphic design and criticism since the early 1990s when the field finally shrugged off the problem-solving model of late Modernism. Of his early efforts during this period Earls writes, "I fashioned myself a later day Herman Melville attempting to craft the great American novel (through this new medium)." But as with most reactionary ideologies, the transition from insurgent critique to mainstream dogma has been problematic. Shortly after the release of Throwing Apples..., Michael Rock published his 1996 essay, "The Designer as Author." The text put the authorial model in a rigorous historical context. Rock breezes through conceptions of the author from Barthes to Foucault, and in the work of Lupton/Miller, McCoy, Carson, Greiman, and others, but he remains skeptical. He writes, "theories of authorship also serve as legitimising strategies, and authorial aspirations may end up reinforcing certain conservative notions of design production and subjectivity." He never fully embraces any of the perspectives he reviews and ends with a string of contingencies: "It may be that..."; "An examination of the designer-as-author could help us..."; "we must still work to engage these problems in new ways"; etc. The only point he makes emphatically is that authorship reflects an insecurity about the merit of design on its own terms.

Spread from Untitled 001, self-published fashion magazine by Mike Perry, 2007. The editor's note reads, "Every issue will be a direct reflection of my inspiration and mood at the moment I'm assembling it." This is the authorial prerogative writ large, but ultimately this magazine will flourish or fail based on the content itself.

Ironically, despite his nuanced analysis, Rock's essay has become a point of reference for precisely the kind of legitimizing strategy he sought to debunk. There have been conferences, exhibitions, essays and countless blog posts devoted to the designer as author. Terms like self-authored, self-generated and self-initiated have proliferated. The School of Visual Arts changed the name of its Graphic Design MFA program (one of the nation's finest, co-chaired by Design Observer contributing writer Steven Heller) to the MFA Designer As Author degree program. The mission statement reads, "The concept of authorship is, first and foremost, rooted in the independent creation of ideas." The text goes on, "The 'MFA Designer As Author' is predicated on the growing need for content providers throughout the visual media." Of course this begs the question, Then why not an MFA in content production? but the program is clearly responding to a change in the aspirations and prospects for students of design. The program that Earls heads defines these prospects in even broader terms. The "Departmental Doctrine" reads in part, "It's a 'love' thing. The goal in life is to quit responding to societal pressure, fear, and desire, and to attempt to gain a deeper understanding of one's true nature."

Spread from And There Will Be Light, self-published book by design team Flag: Bastien Aubry and Dimitri Broquard, 2007

The problem with the authorship model is that it replaces a tangible engaged client with a vague notion of a market, passively waiting to consume (or more likely ignore) the self-generated work of the designer (as author). A quick look through just about any designer monograph reveals the problem with this shift. Iconic works of design have generally been buoyed by the cultural or economic relevance of the clients involved. Robert Brownjohn's titles for Night of the Generals are refined but people remember those he did for Goldfinger and From Russia with Love in large part because of the movie that followed the titles. If you lined up all of Peter Saville's album covers you probably wouldn't pick out Joy Division's Closer as the cherry of the bunch. But the music on that album and the band's continued cultural influence have elevated the cover above the rest. The designer/client relationship is integral not only to the historical fate of a designer's work but to the creative process itself. This is what makes the graphic design process unique.

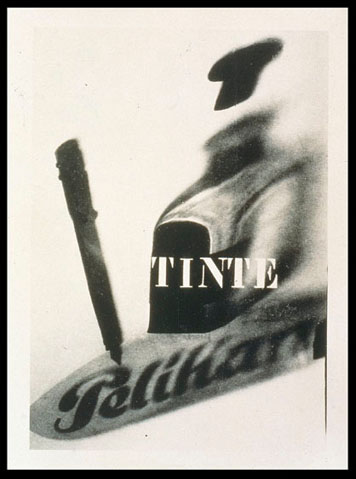

Advertisement for Pelikan drawing ink, designed by El Lissitsky, 1925

In a 2005 essay titled "Fuck Content," Michael Rock revisits the authorship debate. He points to icons of design history such as Raymond Loewy's Lucky Strike pack and El Lissitzky's Pelikan ink advertisement to make the point that content is essentially irrelevant to design quality. He writes, "The stellar examples of graphic design are often in service of the most mundane content possible...But despite the banality of the content, the form has an important, even transformative meaning." Although I agree with the central point, Rock glosses over the critical importance of the client and the economic context of the design. The content of the Pelikan ad may not be compelling but the product clearly was. This goes beyond the fact that Pelikan decided to work with Lissitsky and paid to have this advertisement placed. This poster probably would have disappeared into obscurity without the commercial success of the product. The Pelikan customer was the right audience for Lissitsky's work. This is the symbiosis between the economic and the formal that Rock overlooks.

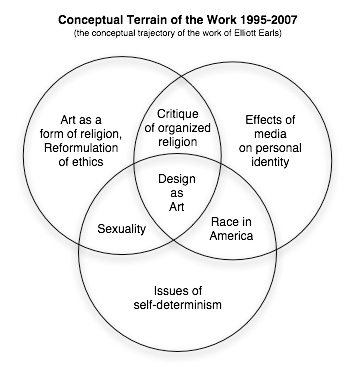

Conceptual Terrain of the Work 1995-2007, Elliott Earls, 2007

Earls has done his best to confound this symbiosis. He proudly describes getting fired from his one and only "real" design job at Elektra Records in 1993 and proclaims, "First and foremost I see myself as a contrarian and a social critic." He takes great pains to distance himself from the design profession, and yet he is the head of a graphic design program and he has been quite successful finding an audience within design. His DVDs are distributed by Emigre, and he lectures and exhibits in Design programs around the world. It is only by putting authorship to the side and examining the context that we get a clear sense of Earls' work.

Kate Valk appearing in a Wooster Group performance of Eugene O'Neil's Houselights, directed by Elizabeth Lecompte, 1998

The economic boom in Lower Manhattan in the mid-1990s is critical to this understanding. The downtown theater community of that era played a significant role in Earls' career. The enduring experimental performance space Here hosted his first performance in 1995 and later he was awarded an Emerging Artist Grant from the Wooster Group. These venues helped Earls shift his work from enhanced CDs to "technologically mediated poetry reading," to the cycles of performance pieces, digital films, sculptural and photographic works he now produces. At that time, the Wooster Group was staging shows that included heavy use of video. They were actively developing an audience for so-called multi-media performances. This brand of technology-infused work was particularly appealing to the creative professionals of Silicon Alley who had a lot riding on the promise of technology and specifically multi-media. In this context Earls' pursuit of a hybrid of technology and performance makes a great deal of sense.

Enron logo, designed by Paul Rand, 1996

Unfortunately contextual questions like these are generally reserved for discussions of "activist" design or social responsibility. Designers are criticized for working for a certain client (say, big tobacco) or lauded for working for others (say, museums). This is a nostalgic view in an economy where tobacco companies are major supporters of museums. Shifting a design critique to an ideological one gets immediately mired in the complexity and inter-connectedness of our global economy. In a world where the Federal Reserve can't sort out who will be left holding the bag in the current home mortgage crisis, it is unlikely that design critics will be able to assess the fiduciary ethics of a print campaign. Perhaps this is another reason that this kind of critique has been unpopular — it is difficult to sort out the significance of design events as they happen. Paul Rand's work for IBM is widely celebrated, but would that be the case if IBM had gone the way of Enron, whose identity he also designed? How has Rand's work been impacted by the disastrous, criminal collapse of the company? This sort of guilt by association (and vice versa) should be a subject of design criticism.

Throughout his career Earls has carefully removed himself from any recognizable graphic design context. He calls his work art or poetry, but this raises an unfavorable comparison to artists like Matthew Barney and Doug Aitken who have used film to organize an inter-disciplinary practice. Earls makes music that is not meant to be listened to as music, and art that's not for the gallery. The downtown theater scene that first embraced his performances is still the most suitable context for his work, but he would probably resist even this as over-simplification. Instead, he prefers to constantly shift his role and context. His work is an extreme example of a posture that is increasingly widespread in graphic design — the designer as dilettante.

The best hope for this new breed of hybrid designer might be that the ubiquity of the authorship model will create a micro-economy that can sustain products whose primary distinguishing characteristic is that they were made by graphic designers. A designer is more likely to be interested in a fashion magazine produced by a designer/editor, and might be predisposed to prefer a mix-tape by a designer/DJ. (Just like the early Internet entrepreneurs were predisposed to like the technology-infused performances of the Wooster Group.) But for every Shephard Fairey, or Jop Van Bennekom who finds a wide audience, there are thousands of sticker-making, tee-shirt silk-screening designers whose zine probably would have been better if it was written by a writer. Without the energy and expertise of the client, self-initiated projects rarely attain the cultural significance necessary to become iconic works of graphic design.

The most compelling section of Rock's "The Designer as Author" examines the theory of the auteur director as conceived by the American film critic Andrew Saris. The connections that Rock draws between the director and the designer are astute, "over the course of a career both the film director and the designer work on a number of different projects with varying levels of creative potential. As a result, any inner meaning must come from aesthetic treatment as much as from content." In "Fuck Content," Rock stands by this as the most enduring part of the original essay adding, "The auteurship, and the meaning of the work, of the director's work is embedded not in the story but in the storytelling." The contingent control that directors and designers have over their work is significant but once again Rock misses a critical distinction — directors work exclusively in the film business and designers float about in all areas of the economy. This fluid relationship to capital means that the designer is fundamentally responsible for his position vis-à-vis capital. The designer's work is defined not just by aesthetic treatment but by the economic and social context they work in.

For the last decade, designers like Elliott Earls have been able to straddle both worlds, keeping just enough client work going to support their authorship. For many, a career in graphic design means being a part-time publisher, writer, filmmaker, DJ or artist. But the quest for authorship may jeopardize the economic and cultural free agency that defines the field. If the designer is author, what becomes of the designer as designer?

Comments [62]

design's outliers do not only push this conservative boundary towards art. in the last few years it has been more and more common for design to push toward technology (science), business strategy (finance), single-source-production (design-build, ie designer as entreprenuer, fuck clients), writing (literature), product development (holder of exclusive intellectual property, enterpreneurship), the list goes on. in fact, i see the traditional center of design less and less interesting, as the margins are where true innovation and invention occur. sure, not all of it is good quality or as mature, but it's still early, and this is a trend that exists in what i think is a larger continuum of expansion. where is it written that one is born with only a "design gene"? what if someone was born with a "design gene" AND a "computational analysis gene"?

the subtext of this post, which can be read as a longing for "purity" reeks of a kind of nationalistic pride that is inherently distrustful of the "other". it is typical defense-of-the-ivory-tower crap. it is inherently biased toward the "establishment". establishment always seeks to protect their interests, outliers always challenge those interests. no, rather, it is the establishment that PERCEIVES that outliers are challenging their hegemony. but in reality, outliers are just kind doing their own thing. "But the quest for authorship may JEOPARDIZE (emphasis mine) the economic and cultural free agency that defines the field..." - oy vay.)

i also completely disagree with the statement "The best hope for this new breed of hybrid designer might be that the ubiquity of the authorship model will create a micro-economy that can sustain products whose primary distinguishing characteristic is that they were made by graphic designers." that presupposes that profiting from the consumption of their "products" is the end-game, which it may be for some - in reality, i think they simply can't help themselves - they NEED to crossover due to complete and utter lack of intellectual and creative nourishment in their present conditions (the center has gotten stale).

was leonardo da vinci a "dilettante"? well, yes. i believe the first step in the mastery of any discipline is the dabbling step. this step builds confidence. they say your IQ increases by some significant factor for every second, third, etc language you master. something tells me the aggregate IQ of the outliers far outweigh the aggregate IQ's of the collective center, simply by virtue of a much, much broader fluency of other "languages" - in this case it's "ways of thinking".

the popular center thinks one way, the outliers think that one way times 10 or more. viva las outliers. we should only be grateful that the petri dish that is design is on a trajectory of expansion, not contraction. it is essays like this that merely prove the conservative center of design is alive and well. will the outliers never be a priest of the center? probably. do they really care to be? no, they don't. there are much bigger and more appetizing fish to fry (somewhere else). will they lose their identity as "designers" (and all attendant privileges that card-carrying "designers" have?) maybe. but their wallets have other cards with plenty more lines of credit attached to them. may we all have this kind of intellectual spending flexibility. it is the currency of curiosity.

09.18.07

12:04

I find it almost laughable that you would foreground (through Michael Rock) the work of El Lissitsky and utilize as your example his advertisement for Pelikan drawing ink, while failing to point out Lissitsky exploration of Suprematism. This is like praising Miles Davis' 1985 rendition of Cyndi Lauper's "Time After Time," while failing to mention "Kind of Blue." You have missed the whole point of Lissitsky as a role model for the contemporary designer. It is the expansive and ambitious nature of his work that is truly awe inspiring. Through your convenient omission you are upholding and encouraging the kind of lack of idealism that has damned graphic design to be the perpetual underachiever of all of the arts. (yes, Arts). I too would hold up Lissitsky. Yet I would focus on Lissitsky as as an example of a modality that is currently excluded from the mainstream design discourse - the designer as artist. The neo-conservative position seeks to define design almost exclusively in terms of a designer-client relationship and an overtly problem solving methodology. Let's take a look at Lissitsky, or better yet John Heartfield. I defy you to show me a more relevant or powerful example of "Graphic Design" than Heartfields' work satirizing Adlof Hitler and the Nazi's. In this example there is a clear lack of client, and Heartfield is acting as an instrumentalist artist. Your argument seeks to enforce the supremacy of an ideological genealogy that excludes the true forgotten power of the post world war I avant-garde.

Your indictment draws into high relief a kind of ridiculous, narrow minded, self-loathing ideology at the core of most mainstream design discourse.

warmest regards,

Elliott Earls

Designer-In-Residence

Cranbrook Academy of Art

09.18.07

12:27

09.18.07

01:08

As a 2nd year student at the School of Visual Arts, designer as author program, I have seen the potential and success of designers moving beyond traditional form giving and towards a deeper role in the lives of projects inside and outside of the client/designer relationship. The best example of this is Debra Adler's ClearRx project. A self-initiated project that helped a whole industry reevaluate the role a designer. So the potential inherent in design authorship should not be discredited by an uneasiness with the economic and cultural viability of a project. But embraced for the potential to expand the not only the role of a designer (something already in full swing), but also the much needed diversity of designers.

09.18.07

01:47

And Earls' work is what it is. Goofy, funny, and sometimes thought-provoking. He's neither the most accomplished musician in the world nor the greatest film-maker, but he sort of does it all. I think the multi-disciplinary quality of his work is exactly the thing that recommends it.

Anyway, no-disrespect to Mr. Siegel, but this article seems to be a product of navel-gazing. Work is work, whether it's applied or it stands on its own. The fact that Earls doesn't do much (if any) commercial work is beside the point. The point is that the work is good.

09.18.07

01:52

-dmitri

09.18.07

02:04

But, with the way things are everyone'll find their niche. If there are pockets of likeminded persons, why is that a bad thing? We've already seen a form of tribalism in music and in art. Discussions like this article show that there clearly is one in design.

If people are against these small, personal groups; what are they for? A clean, client dominating business environment? When you look at the future, in movies or magazines, they typography of the utopian world is always neo swiss modernism, clean hybrid digital vector aesthetic.

Why can't we have a David Cronenbergian typography? Where the future is hybridized to the point of fleshwords and ornate majuscular illumination?

Concerning the Designer as Author, it is a sticky situation after all. Design, as its operating system, emphasizes the client's view over the designer's. It doesn't matter what stories that you might have to tell, as long as you can use your Homer/Aeschylus skills to paint the perfect picture of a breadmaker. But this is fine.

At Cranbrook, or any other program at the Grad Level, the students came for a reason beyond being a communication technician or ideological tradesperson. If you have a story within you, you must find a way to tell it. If that story is burning you up, in an immolation scene worthy of Wagner, you're kidding yourself by doing a certain type of work squarely in a business, commercial friendly realm.

On the inclusive side: as designers in these programs, we are told to find a network of enterprises to sustain us in all facets of our potential, personal careers.

If you have the opportunity to try something, why not?

A toolset of design technologies can be used for any purpose including or beyond design proper. This argument seems snuggly in a isolationist perspective. (as Gong Szeto has gone into further detail) It could be argued that, if art is a narrative about technology facilitating content, then people such as Elliott are trying to make things possible.

This is one true path of the artist. To make the impossible, possible. Who knows if Elliott has actually conjured up demons and djinns? He has consistently throughout his career pointed the way to new a media synthesis via the road of typography and design.

In other words: discovering Elliott Earls is like the first time a caveman discovered you could eat an oyster.

Who'd guess that it tastes good.

09.18.07

03:37

In a visually saturated, design savvy culture, the challenge for graphic designers is not to simply visualize the many clients' overabundant messages, but to create messages worth visualizing (or singing, or dramatizing). And who determines if an idea is worth visualizing? The client? How many clients pay designers to litter our mailboxes, screens and billboards with uncritical, uninspiring graphics? (At least enough to deeply bury every self-authored sticker and silk-screened t-shirt in existence.) The designer has the power to determine if an idea is worth visualizing. The designer can choose what defines himself, his work and its boundaries.

Siegel mentioned Lissitzky and his work for Pelikan as an example of the proper way to design, but (as Elliott pointed out) neglected to mention Lissitky's true significance - as an agent of change, a propagandist and a master of photography, typography, architecture and design. If Lissitzky is a model graphic designer, then Earls exemplifies what he might look like today.

While our ability to communicate expands, technology blossoms, populations grow; restricting the field of graphic design to historic boundaries does nothing to further good, successful, meaningful or ethical design. Strict 'designer as designer' answering client needs without questioning this working model ignores the cultural conscience that is rising, calling for social responsibility.

Earls 'constantly shifting role' keeps him nimble, athletic and fit to respond to cultural concerns. His ambitious scope of work shows that graphic designers need not be mere technicians developing the ideas of others. We can do so much more than love what we produce. We can produce out of love. We can draw inspirations from our own fears, our personal values OR our business contracts. Earls' work represents freedom. It questions context, defies expected production value, mocks design proper. It is fun, funny, dead serious, and relevant. It should be celebrated!

09.18.07

04:42

Does Graphic Design need to be protected? Could the designer as author, or perhaps the designer as artist, or maybe the designer as human being be such a horrible threat to this field? Has graphic design been so well defined in the last 100 years that no room exists to expand its definition? Or perhaps no room exists to insure the safety of its current definition? Maybe there would be room if only designers were intelligent enough. Because I have nothing meaningful to say since I'm not a professional writer I'll go back to drawing exact copies of flowers because we all know thats what Picasso should have done.

Thanks,

Jordan Gushwa

09.18.07

04:46

In the Designer as Author MFA program, where I am a student, we generate projects with an entrepreneurial spirit. Not only that, we wouldn't refuse additional opportunities for commercial success either.

09.18.07

04:52

09.18.07

05:08

Design is the only profession I can think of in which a great number of its practitioners actually would like to be doing something else (okay, there are all those actors working in restaurants, but still). I became a designer because I wanted to be a designer. I'm fascinated with the process of making things in collaboration with others and seeing how form and content can interact. Ed Fella has called his personal work "art design," and that makes sense to me--he uses the tools and language of design to make art, just as Elliott does.

Dmitri asks "if the designer is author, what becomes of the designer as designer?" I don't think designers shouldn't also be writing and making their own things, but we should remember and celebrate the traditional role of the designer--to work with others to help present their content to an audience. It's a cliché, but everyone really can be a designer now. Authors typeset their own books and create their own covers. But a designer is a thing to be (and be proud of), whether you're an "author" or not.

Earlier this year I got a call from the Art Directors Club. They wanted to pair up designers who had been included in past and present Young Guns shows and have them present their "personal work." My immediate response was that I didn't have any--all my work is done with clients. I had to turn down their invitation. But now I realize that all my work is personal, too. I've never had that much interest in doing "art design." For me choosing whom to work with and how to do the work is expansive and ambitious--and just part of being a designer.

09.18.07

06:19

Has the dominance of the "designer as author" model transformed graphic design into a vague form of cultural production?; and, Is the allure of the legitimacy of authorship pulling design away from the defining characteristic of the profession — the designer/client relationship?

Way back in 1964, when Ken Garland wrote First Things First, he urged designers to reconsider opportunities outside "the noise and high-pitched scream of consumer selling in favor of applying their talents to promote education, culture and a greater awareness of the world." It subsequently became a rally cry for the re-evaluation of the profession's priorities and suggested that rather than applying their skills to selling dog biscuits, french fries, detergents, hair gel, cigarettes, credit cards, sneakers, light beer and heavy-duty recreational vehicles, Garland advocated "injecting passion, truth and reality into design work" in an effort to inspire "the other media through which we promote our trade, our education, our culture and our greater awareness of the world."

Frankly, I believe this is exactly what Elliott Earls is doing. Exactly.

Earls, through his vast body of work (all of it, not any one part), is seeking to further the contributions of design (all of it, not any one part) with his inspiring, multi-disciplinary approach. He is a designer and artist, and as such, has helped extend the boundaries of the definition of what "we" do.

You also asked: What happens to designer as designer?

Short answer: You've got to be kidding.

Long(er) answer: Actually, I give up. It's questions like these that make designers in every discipline shake their heads in shame. I'll leave it at my short answer. I have too much work to do for clients.

09.18.07

06:50

In his work I see a blurring of the traditional distinction between form and content. Less controversial designers have taken a similar approach toward claiming authorship- notably Paul Rand and Alvin Lustig (who placed their signature prominently on what would be considered editorial design or illustration work), as well as Bruce Mau (who dropped the "graphic" moniker from his title years ago), and Ryan McGinness (who creates very "graphic" art and design objects). The difference between Earls and practitioners like Mau and McGinness is that the latter are not creating polemic graphic design. Rather they position themselves outside the field- in effect anesthetizing the conversation within the field.

I find it telling that in Mr. Earls' response to this article he defined his title as "Designer-In Residence" at "Cranbrook Academy of Art" in response to the article. Does this imply that he is first and foremost an educator. In this light, I see his approach to design as quite logical. Isn't the model for the Master's program in Graphic Design at institutions like Cranbrook, CalArts, and Yale to essentially create experimental, polemic, innovative (and yes self-initiated) design? Mr. Earls is fulfilling his role as a Cranbrook Designer-In-Residence by leading by example.

09.18.07

06:54

Really? Perhaps the quest for authorship may jeopardize the economic and cultural free agency that defines a given designer, but I think it's a very large leap to assign such possible change to "the field".

If the designer is author, what becomes of the designer as designer?

This is why one school is different from another; why some designers live and die for creating infographics, others for making t-shirts, others yet for making music. It's hard to take that question seriously without first considering academic programs which seem to be polar opposites of the one at Cranbrook. What about the masters programs at IIT, CMU, and others like them? Should we instead be concerned that the whole of design will be carried away into a realm of organizational problem solving? Hardly. And let's not overlook the slew of other academic programs at instutions well- and lesser-known.

Gong Setzo talks about innovation on the fringe, and thank god for those practicing on the boundary of "normal" design. It was Cranbrook's program under the guidance of McCoy and Makela that drew many into graphic design - myself included - and Earls' tenure is, at least as I'm concerned, a wonderful continuation of a tradition that not only allows but encourages real exploration, even if that sometimes means "failure" by some standards.

I had the privilege of interacting with Earls at DesignInquiry in 2005 and have not been the same designer - or person - since. The claim that Earls has "carefully removed himself from any recognizable graphic design context" is ignorant of his involvement in programs like DesignInquiry, his time at Fabrica, his many graphic design visiting lectures and writes off his tenure at Cranbrook, among many other things.

09.18.07

07:11

09.18.07

08:06

Earls was a worthy focal point for this piece becuase his work and reputation are more than capable of withstanding the critique but there's a larger issue that motivated the writing. Basically (and I say this an unrepentant dilettante myself) it's getting a bit tired to claiim that being a designer/author is somehow transgressive. Hasn't that become the norm? When the grad programs at SVA and Cranbrook are based on authorship doesn't that meant it has become the status quo?

I just thought, now that we are pumping out a generation of designers who think client work is for suckers maybe we should take a second look, you know? As Scott alluded to, author-lust can be a very insidious form of the "self-loathing" that I'm getting accused of.

09.18.07

10:16

The first quote is from the second paragraph and the rest are in order of appearance:

Of his early efforts during this period Earls writes, "I fashioned myself a later day Herman Melville attempting to craft the great American novel (through this new medium)." But as with most reactionary ideologies, the transition from insurgent critique to mainstream dogma has been problematic.

Problematic for who? Elliott? The design field? Mr. Siegel? Mr. Siegel, in his characterization, equates most reactionary ideologies as essentially the same, but why? One may react against the prevailing ideology of the mainstream in particular without reacting against the concept of the mainstream per se. In which case why would the transition from "insurgent critique" to "mainstream dogma" be problematic? When has Elliott ever made an argument against the mainstream or the popular per se or in abstracto? I have never heard one. He argues frequently against the prevailing mainstream, but if one were to make any real attempt to comprehend his work or his philosophy one may find that he would be perfectly content if his approach to design were "mainstream dogma." Mr. Siegel here implies a generalized equanimity (between "most reactionary ideologies") that cannot necessarily/inherently be applied to all the particularities it claims to encompass.

Is the allure of the legitimacy of authorship pulling design away from the defining characteristic of the profession — the designer/client relationship?

This is the first of several either/or propositions, but Mr. Siegel is the one here arguing for either the legitimacy of authorship or the designer/client relationship as a designer's only two options. The implication is that the rest of the design community is in agreement, because otherwise it would not be such a blasé offering of supposed alternatives. But is it not conceivable that there are more than two possibilities?

The text put the authorial model in a rigorous historical context. Rock breezes through conceptions of the author

Again Mr. Siegel makes a statement that on the surface sounds convincing and authoritative, but reveals itself to be subcritical and generalized. Why would I believe that Rock places the "authorial model in a rigorous historical context" when in the very next breath I am told that he "breezes through conceptions of the author"? Anything rigorous, by its nature, precludes it also being breezy.

Not to mention that here Mr. Siegel sets up a crucial false comparison. By setting up the writings of Michael Rock as the touchstone or manifesto for the notion of the "designer as author" Mr. Siegel has de facto insinuated Elliott Earls specifically, and the majority of "designers as authors" in general, as implicated in or supportive of Rock's arguments. But what do these writings have to do with Elliott Earls specifically, or the majority of "designers as authors" in general? In using this false comparison Mr. Siegel sets up a crucial conflation of separate issues: Michael Rock's arguments for or against (it is not made clear in the article which it is) design authorship are conflated with Elliott Earls' definite arguments for design authorship, and in the process Rock's arguments against content are implied to be Elliott's as well.

The problem with the authorship model is that it replaces a tangible engaged client with a vague notion of a market, passively waiting to consume (or more likely ignore) the self-generated work of the designer (as author).

In what way, precisely, does the "authorship model" replace a "tangible engaged client with a vague notion of a market"? Here is yet another either/or proposition: either a tangible client or a vague market, but that is a specious equation in that we are led to believe those are the only two options available, which is demonstrably untrue. Why are we consistently given only two possible models that a designer can aim for? What about the abundance of niche markets available to the enterprising designer (as author), or competitive grants, or a group of interested investors, or a patron, etc. And just how often is the client, in the model Mr. Siegel is clearly advocating, TRULY engaged, or even tangible? I have worked on many a design project in which the client was neither, unless Mr. Siegel means tangible only in the sense of a name being on an email or a check (and there is no mention at all of just how difficult it can often be to actually get a signature on a check for a client based designer). One very important, and completely unfounded, implication here is that creation is only valid if there is a clearly defined and pre-established consumer awaiting the creation in question. But what of the plethora of examples throughout history that prove otherwise?

In a 2005 essay titled "Fuck Content," Michael Rock revisits the authorship debate...The content of the Pelikan ad may not be compelling but the product clearly was.

In this paragraph we are once again being hoodwinked. The entire paragraph implies that all authors as designers are following Michael Rock's notion of content being unimportant and/or invalid. Once we have been required to accept this as our only option Mr. Siegel goes on to imply that, if this is the case then the designer requires the economic backing of a client to make work with any cultural weight or staying power. What does this argument have to do with Elliott Earls? Elliott is unquestionably creating work in which content is of prime importance. As a matter of fact one can easily find any number of arguments he has made that he sees form and content as inextricably linked. So, why is Mr. Siegel waxing philosophical about an argument made by Michael Rock against content, which is wholly irrelevant to the mode of designer as author that Elliott Earls typifies? Perhaps because Elliott is being used as a straw man? A convenient (if completely fallacious) symbol of an abstract concept, "designer as author".

He takes great pains to distance himself from the design profession

A completely unqualified assessment that we are to take as obviously true, precisely due to said lack of qualification. In what way has Elliott taken great pains to distance himself from the profession? By actively participating in its discourse? By taking the role as head-of-department at one of its leading institutions? By hyper-actively pursuing the opportunity to lecture in its regard at design institutions throughout the country and beyond? By designing typefaces, posters, books, DVD packages and interfaces, CDs, websites, and more? To say this is analogous to ideologues accusing Noam Chomsky, or Howard Zinn of being traitors simply for having the unutterable and contemptuous gall to critique America. Just because it is done in an offhanded or seemingly innocuous way does not mean that a statement is not meant to have a wounding effect, indeed these are the kind of statements that in actuality have the most insidiously devastating effects.

It is only by putting authorship to the side and examining the context that we get a clear sense of Earls' work.

Why exactly is this the ONLY way to get a clear sense of Earls' work? And where exactly has Mr. Siegel dealt with authorship at all in the first place?

In this context Earls' pursuit of a hybrid of technology and performance makes a great deal of sense.

No, actually it doesn't. So, we are to believe that Elliott Earls' and the Wooster Group's (an avant-garde theater troupe that has been pushing the boundaries of theater for over 30 years) decisions as artists/authors can actually be traced to their recognition of "the creative professionals of Silicon Alley who had a lot riding on the promise of technology and specifically multi-media" as a bountiful untapped market? So really Elliott, and even the Wooster Group, aren't artists or authors after all they are just designers, like the rest of us, who happened to be birthed out of their specific market/marketable context. Underlying this entire argument is the a priori assumption that ALL people make ALL decisions for the same reasons, namely money and/or self-aggrandizement. Any other possibility would just be unthinkable. And so, if we can just figure out the specific economic context that someone came from we can calculate their true motivations. Of course this assumption flies in the very face of the concept of an author in the first place. To Mr. Siegel the idea of an author, someone who makes decisions founded/grounded in a principle, value, norm, or deeply rooted (and therefore radical) imperative other than money or self-aggrandizement, is apparently inconceivable.

His work is an extreme example of a posture that is increasingly widespread in graphic design — the designer as dilettante.

But this is not Elliott's posture, it is Mr. Siegel's characterization of Elliott's posture. And it once again equates all designers who attempt to work in multiple mediums as dilettantes. But why is this not then true of artists? Or directors (David Lynch doesn't get lambasted for also painting)? Or for that matter why is it not true of El Lissitzky who (as Elliott pointed out above) is used as a stereotype when it suits Mr. Siegel's polemical purposes, but whose forays into a wide array of other mediums, modes, techniques, and genres are conveniently neglected when it doesn't? To argue the quality or validity of Elliott's authorial powers is one thing, to argue the validity of venturing into multiple mediums is quite another. Mr. Siegel apparently takes for granted the invalidity of Elliott's authorship, without in any valid or critical way proving or even arguing it, and then uses that unfounded given to "prove" that the "designer as author" is a fool's gambit, a dilettantish dabbling.

But for every Shephard Fairey, or Jop Van Bennekom who finds a wide audience, there are thousands of sticker-making, tee-shirt silk-screening designers whose zine probably would have been better if it was written by a writer. Without the energy and expertise of the client, self-initiated projects rarely attain the cultural significance necessary to become iconic works of graphic design.

And similarly for every J. Abbott Miller, or Michael Rock who finds a wide clientship there are TENS of thousands of template making, "info-burger flipping" (to appropriate one of Elliott's phrases) designers whose brochure would have been better if it had been designed by a more experienced designer. And EVEN WITH the energy and expertise of the client, client initiated projects just as rarely attain the cultural significance necessary to become iconic works of graphic design. So what's the point? It's hard to make iconic works of graphic design?

Just look to Mr. Siegel's title to be told explicitly the implications of this article: "Designers and Dilettantes". Mr. Siegel is not arguing against the notion of designer as author, authorship in design is taken as a foreordained impossibility. What Mr. Siegel is saying is that in the world of design you have 2 options: You are either a designer (as supposedly defined by Mr. Siegel and his "camp" or cult) or you are a dilettante, a childish naif playing at a man's game. An appropriate subtitle for this piece would have been: "You're either with us or against us." Mr. Siegel seems to believe that by being a part of and defending the status quo one is somehow not a reactionary, but in truth this is a quintessentially reactionary article. It does nothing in the way of incisive explication nor interpretation. It makes no attempt to comprehend the implications of any of Elliott's abundance of work. It doesn't even attempt to deal with the obviously radical distinction between Michael Rock's stance on design and Elliott Earls' stance on design, though these are the two designers that are pitted in comparison to one another throughout the article.

Casting Elliott Earls as a dilettante, implicitly in league with a mass movement of "designers as authors" who are explicitly or implicitly aiming to erode the foundations of the design profession, is subcritical and propagandastic mendacity. It does an enormous disservice to the consistently ambitious, ground breaking, dedicated, and masterful efforts that Elliott has displayed in his work for well over a decade. It does a disservice to all of the other "designers as authors" who may not see Elliott as a role model for what they are attempting at all. It does a disservice to the realm of design criticism.

I am personally overtly at war with this kind of parochial and proprietary narrowness, which disguises itself as cosmopolitan and sophisticated broadness and/or depth. A cosmopolitan is a citizen of the cosmos, and the cosmos has more than ample room for more than two perspectives and approaches to design. One does not have to exclude nor undermine the other. The implications of Mr. Siegel's article reveal that he is actually a provincial citizen of the Design Ghetto, taking pride in his marginal role and being proud to defend it. That's all well and good, but I don't see why that means everyone else in the field should have to be subject to such a narrowly prescriptive approach to the profession. Some of us may prefer to consider it a vocation, that is, not something we profess, but something for which we were called.

Truly,

Joshua Ray Stephens

(In disclosure: I am a long-time collaborator with Elliott Earls and a graduate of the Cranbrook Academy of Art, but I can say truthfully that this response is about values and principles, not about affiliations and allegiances. Had Mr. Siegel written an in-depth, logically consistent, and well considered refutation of Elliott's work I can guarantee I wouldn't even have responded.)

09.18.07

11:51

09.19.07

12:11

Designer as author hasn't become the norm as you say but rather, necessary. We designers have found and implemented a way to expand and keep our field from becoming stagnant and overthrown by things like shitty DIY (not that DIY). In any profession new boundaries mean new territories and new territories mean new discoveries. If we start constricting instead of expanding designers should find a way to expand. (I feel like I've just gone full-circle here.)

09.19.07

12:24

In this case, the word "as" implies that being a designer is not enough by itself anymore and designers should act like authors too in order to succeed. That is one of many wrong implications.

However, when "as" is replaced by "and", suddenly a respectful relationship starts between design and authorship. That way designer retains to be a "designer as designer" (for your psychological convenience) while collaborating with the concept of authorship.

That said, I strongly disagree that designers as authors think that client work is for suckers. That is such a wrong conviction. First of all being a designer and being a designer as author is like apples and oranges. No. I'd like to correct myself; being a designer and being a designer as author is like granny smith apple and macintosh apple. They are both apples but different kinds.

Seems to me like you are trying to pick a certain kind of apple over the other kinds and declare it as "the right apple".

On that note, I also disagree that designer as author is neither the norm nor the status quo. It is only a way of practicing design which is a profession where a practicer do not need to accuse a fellow practicer for being a sucker just because they don't practice it the same way.

09.19.07

02:16

"...it doesn't matter what the work is about, the designer's hand is visible in the treatment, not the writing [...] to fully recuperate design from its second-class status under the thumb of content you must take another step. You must say that treatment is a kind of text itself, equal to, and as complex and referential as, traditional forms of content. The materiality of a designer's method is his or her content and through those material/visual moves, a designer speaks."

The irony is that you can never really 'fuck content' since as a designer what you do is give shape to content through "typography, line, form, color", rhythm, and organization, regardless of whether you or someone else generates the content. What the essay argues for (and what i think is the 'fuck content' part) is the recognition of treatment as a text in itself that reflects "a philosophy, an aesthetic position, an argument and a critique" that belongs to a specific designer or design group. I think this is a complex position to advocate, as it asks critics and designers to look at a subjectivity expressed through very public and utilitarian ways. The read is not overt nor in-your-face, and therefore less easy, since form tends to be subsumed by its role as a conveyor of content. But treatment as a text can be very complex and convoluted across a single designer's (or design group's) body of work, proof of a self-propelling interest that happens whether a corporation provides content or a designer does. There are examples of this: In graphic design, Wim Crouwel's, who explored the idea of the module and the grid across a wide range of materials, and Tibor Kalman's work on Colors, who created editorial statements through basic image research, sequencing, and word/image pairing.

The moral split between "good" (personal or cultural) and "bad" (corporate) work is a false one as Dmitri points out, though the example of Paul Rand's Enron logo and "guilt by association" as a subject of design criticism is a bit heavy-handed in an adbusters sense. Paul Rand and his logo pretty much had nothing to do with Enron's actions, though he benefitted financially from doing work for them. Not only as designers but also as citizens, we are all associated and benefitting from our economic system. "Cultural" work can often times be very boring and conservative, "Personal" work can be too self-absorbed to access, and "Corporate" work can sometimes be more entertaining, poignant, and current than anything else, but it's all made possible by a priveleged position in the world economy.

Does that mean one should not design large projects when given the opportunity? Non Serviam? In architecture, the Seattle Public Library is an example of design as philosophy, aesthetic position, argument, and critique. There is no content in a traditional sense created. Through organization of space according to function and selection and treatment of materials, OMA express a point of view on architecture through a piece of architecture, and at the same fulfill their civic duty by creating a space for a public library. It is avant-garde design for both your grandmother and the design world. This to me is more interesting than art.

09.19.07

03:12

Each proved that designers needn't be stuck in one medium, doing one thing, adhering to a single style or mannerism. They were, again in a broad sense, entrepreneurs, who saw design as a means to express, create, and fill real needs in the marketplace.

"The Designer as Author" in this context is a term you can take literally if you choose (as one who authors content - word, picture, or whatever else) or metaphorically (as one who develops alternatives to conventional practice). Or, actually, you can read and practice it both ways. Elliott Earls does both, and, incidentally, he was doing so since before the term was coined.

Some of our students follow the more expressionistic path, but on the whole SVA's MFA students are required to "invent," "author," and "fabricate" ideas that have a definte audience (nota speculative or annecdotal one). Rather than shirk the client/designer responsibility they embrace all aspects of it in a rigorous manner. Frankly, it gives them greater respect for the process. And while some of their authorial or entrepreneurial work doesn't reach the publics they are targeting, as we would like, it is not for lack of rigor in trying. conversely many do and they are now part of the world no different than if they were developed by non-design entrepreneurs. Our students and grads definitely are designers AND authors, but they are also designers who, building on their skills as designers, take charge of the entire creative and business process.

09.19.07

06:23

I would first like to make it clear that I sincerely appreciate your critique, and would like to applaud your effort. Having said that. I'd like to address one point from your follow up post. I realize that there are two issues at play here that are being conflated for rhetorical reasons. The first being this nebulous concept of "designer as author." The second being the character of my work specifically. I'd like to address a few issues as they pertain to my work specifically. In your follow up, (in essence) you provide a synopsis of your argument by stating;

"Basically (and I say this an unrepentant dilettante myself) it's getting a bit tired to claiim that being a designer/author is somehow transgressive."

I think this statement illuminates a vast chasm between what you may believe my motivation to be and what I am truly attempting to achieve. I think it is also an arrow through the heart of the problem. The notion that I have established "transgressive" as a criteria for my work, or for my role in the graduate studio at Cranbrook, is simply wrong. My work has developed through a passionate, ceaseless, disciplined and rigorous attempt to invest it with power. A clarification of terms is obviously now needed. "Power?" Yes, as you correctly pointed out I have stated "First and foremost I see myself as a contrarian and a social critic. And while I realize that my work appears highly formal, at it's core it is essentially Instrumentalist." Put as simply as possible I am attempting to "move" people with my work. My goal has never been to be overtly "transgressive," any radicality that might be ascribed to my position is the result of simply proposing an alternative.

You seem to be assuming that I - and by analogy, my "people" - have set out on this path to be "transgressive." This is like suggesting that Charles Bukowski or Henry Miller, set out to be transgressive rather than to chronicle life through the structures of literature.

The most cogent example of how my approach to authorship may differ from what I believe you are proposing can be found here:

http://www.theapolloprogram.com/SaranayPerf.html#superman

The second issue I would like to address is equating me with a "dilettante." Dilettante I am not. I've dedicated nearly every moment of my waking life since the age of 17 to the pursuit of powerful art (yes, once again design is part of that). While the legions of designers took coffee with clients in elegant pants, I was grinding it out in a windowless room rigorously studying music theory, programming, letter-form design and producing highly (economically) speculative works. Dabbler I am not. Equating me with the legions of part time DJ's, publishers and musicians is a slap to my work ethic, discipline, and to the legitimacy of the venues that have graciously hosted my work. A qualitative assessment of my work is a completely different issue. Is my work any good? You're entitled to your well informed and reasoned opinion.

I'm very happy to engage in this conversation. I vigorously welcome any discussion of my work, good or bad. Hell, it's my favorite topic of discussion.

warmest regards,

Elliott Earls

Designer-In-Residence

Cranbrook Academy of Art

09.19.07

09:28

THIS IS THE LINK IN THE POST ABOVE:

http://www.theapolloprogram.com/SaranayPerf.html#superman

09.19.07

09:33

09.19.07

10:19

It's not wrong that we are attracted to other art forms. I'm in a band, and I love being a graphic designer. The band is moderately successful, and I design our album covers and website. But I compartmentalize: I don't see my music as an extension of my design work. I also don't see music as artistically superior to graphic design, but that doesn't mean everybody else feels the same way.

Let's face it. Few outside of the graphic design world will recognize it as anything other than a service. There may be countless graphic designers who are also great artists, filmmakers, and musicians, but when they present themselves as designers-as-artists, designers-as-filmmakers, or designers-as-musicians, they are going to have a much harder time with both disciplines.

09.19.07

10:50

Graphic design is only a service when the designer is solving the communication problems of others. The lines get blurred when designers (or artists) use the tools and/or media of design to solve their own communication problems.

09.19.07

11:42

09.19.07

01:00

That's the funniest thing I've read on DO.

09.19.07

01:55

09.19.07

01:55

In Earl's case he othered his way to the design outside and seems to be looking not back towards design but beyond. I cannot question this personal choice but in essence the further he positions himself to the outside of the margin, the less he has to say or reflect upon the center from which he sprang. This seems to be the nut of Mr. Siegal's argument and I think it is an interesting and valid point both with regard to Mr. Earls and with regard to the mechanics of the design profession.

My own view is that Earl's is sincere but has nothing to say to design at this point and in fact now is simply poaching some aspects design craft in pursuit of other efforts. For me its art/cultural commentary. It uses media as a medium but it is hardly design. It can be assessed in relationship to other people doing the same thing but that is another topic for another post.

Surely art and design do overlap. In this regard I think it is unfair to say that because an artist/Earls looks to design for inspiration that the person who notes this should by definition be called a conservative. I think that Mr. Siegal is simply trying to define language precisely in order to communicate clearly. Finally Mr. Earls himself says that he is first and foremost involved in a "pursuit of powerful art". That is fine but it is different than design. I think he is a great visiting artist that surely would inspire designers and I would encourage him to talk to as many designers as possible. Nevertheless I think Ray and Charles Eames would be at best amused and more likely confused by anyone who would attempt to equate their sense authorship and its role with the authorship of Earls.

09.20.07

12:04

As Joshua pointed out:

"Underlying this entire argument is the a priori assumption that ALL people make ALL decisions for the same reasons, namely money and/or self-aggrandizement."

It seems as though Dmitri is passing a value judgment on success levels here, which proves a certain amount of naiveté to the actual genre of authorship in any discipline. A valued measure of success such as Shepard Fairey's, who's successes, lets not forget, are well cemented in both the self published and commercial world, are NOT what everyone who lays pen to paper seeks. Not to mention the primary premise of Fairey's Obey work stems from an analysis of the client-esque virus of brand based message spreading and media saturation. Sometimes these personal expressions stem from a desire to connect to a certain community or simply the desire to see what happens. My point being the end goal is not always clear, and sometimes it's not always meant to be public either. The idea that we are working as whatever creative label we choose to give ourselves simply to gain some type of public or monetary success is very "reality television," extremely conservative and grossly American. Look at my splash and applaud it.

To point an accusatory finger at the SVA program or Cranbrook (Cranbrook?!) as conservative is really just elitist pretense. In my quest for grad school education I found FAR more conservative programs elsewhere. Not everyone is looking for an Art Directors club medallion or to run an enormously successful studio, and not everyone one wants to design museum catalogues either. The binary nature of Dmitiri's argument seems to display a lack of true exploration into the possibilities of a designer as anything more then a service to commerce.

The final point I'll make is the truly misinformed assumption that the silicon valley boom had such a significant impact on Elliott's early performance work is just ludicrous. Any amount of study into new media and performance art shows a reasonable build up to the explorations of the late nineties as reliant on the past work in the medium and the obvious cultural shifts in how we share information, generate content and the accessibility of the technology. Why would silicon valley care about this work? What money could truly be made from it? It's just a short sighted way to write off a form that challenges tradition. Not to mention simply dismissing the fact that the work was really GOOD and deserved a place in that world.

I'm a grad of Cranbrook and while Elliott and I disagree on things, I do give him mad props for going after his "bliss." What if everyone actually did this in life? Maybe we wouldn't have to worry so much about our client relationship strategies. And contrary to Dmitiri's misconception, the program is not about designer as author. My experience was much more about being a multi-disciplinary designer/artist and discovering a voice amongst my peers while discussing and reacting to the contemporary cultural climate. It was not about some commercial based practice of generating psuedo-cultural niche products (there are other programs I've seen take this approach, why did you fail to point them out? SVA seems a bit obvious being that their program is called "Designer as Author"). I wonder where Dmitri got this misconception? The experience not only made me a better DESIGNER it made me a better artist/musician/writer/etc......

09.20.07

12:10

The Renaissance-men of the information age. Cultural DJs. Those who have either the ability or desire to design/write/direct/compose/skate.

Mediacrats who see no lines between disciplines but who are geared toward product completion with little regard for traditional job titles or archaic credit lines with the work.

Slashers tend towards collectives and anywhere where creativity becomes the true bottom line. Sure, all aspects of the Slasher's game might not be up to snuff, but they are dedicated and interested in improving them all.

Beware the Slasher...

09.20.07

12:51

Designer as author = designer as dilletante.

Therefore, are we to make this logical conclusion:

Author = dilletante?

The whole "designer as author" notion is pretty much bullshit from the get go. What distinguishes a "designer as author" from a "designer?" The suggestion seems to be that, if work is self-initiated, then one becomes a "designer as author," for better or worse.

The bottom line is, in fact, that all designers are authors. Every designer is the author of his/her work, self-intiated or not. If a client hires me to convey some complex information, and I develop a unique visual expression of that information . . . well, guess what? I'm the author of that. If I go out and self-publish an anti-war poster and plaster it all over town . . . well, I'm also the author of that.

Everyone rcognizes that Pelikan Ink ad as the work of El Lissitsky. Why? Because, as the designer, he's essentially been creditted as being the author. Nobody would say that Pelikan Ink is the "author" of that ad. Granted, they were the client. But in the world of art, we'd call them the benefactor or patron. Pelikan may well have had the wisdom to hire El Lissitsky, pay him, and publish the ad, but they did not author the ad. The Medici may have had the wisdom to sponsor Leonardo, but they are not the authors of his work.

Once you understand that all designers are authors of their work, you realize how utterly trite and meaningless this "designer as author" concept is.

That aside, it seems to me that Elliot Earl's work isn't even really graphic design (I don't mean that in a negative way). It's filmmaking, Or art maybe. Why on earth does he have to be labelled "designer as author" or, far worse, "designer as dilletante?" How insulting!

Mr. Earl may happen to be head of 2D Design at Cranbrook. And he may well do some graphic design for clients. He might also do self-initiated graphic design. But he's also making art, film and music, apparently. Seems like he's engaged in multiple disciplines. Fantastic! He may be a designer AND a filmmaker AND an author AND an artist AND a musician. Spectacular!

Is Earls' work any good? That's a different question. But, Dmitri is belittling and insulting Earl's obvious commitment to his work by applying the absurd and meaningless "designer as author" label. Imagine how different this essay might read if Earls were refererred to as "an artist who draws from many different disciplines, including graphic design."

Finally, I'm getting a clear implication from this essay that this so-called "designer as author" movement is somehow dragging down the design profession. That's preposterous.

09.20.07

09:12

Eleven.

09.20.07

10:00

I am deeply concerned with the question, "What is graphic design?". I think it is the role of criticism to wrestle with questions like this even after they have been addressed in Emigre. I am not content to say, "Everyone should be free to do whatever they want. Who cares?" I care. Elliott Earls clearly cares. People can do what they want but it's not the role of the critic to give everyone a free pass. Arguing that work should not be criticized because the maker "wanted to do it" is just lazy and is an argument for weak criticism.

09.20.07

11:35

I have found it interesting to note which articles here at Design Observer generate a lot of comment and which ones don't.

An article about that could be interesting.

Sorry for the interuption :-)

Carry on.

09.20.07

12:24

Instead of posing the question of what graphic design is, you seem to be making a statement as to what you think is not graphic design.

09.20.07

06:16

I don't question the legitimacy of the discussion. Rather, I challenge the selection of the specific critical framework within which to have the discussion and the overall selectivity of the critic's examinations.

Why, for a work produced in 2007, reach back 11+ years to "The Designer as Author" as a critical lens with which to examine it? Rock's essay was instantly suspect as it failed to include Throwing Apples at the Sun in its examination. Is this posting an effort at rehabilitation? How is rehashing Rock's conservative and profession-centric arguments bringing something new to the conversation?

The clear implication is that in the intervening years no other substantive analysis of Elliott's work and the "designer as author" phenomenon has occurred. The primacy of "The Designer as Author" is presented as a given, where it is actually arguable and demanding of a proof. Because I'm self-absorbed, I use my own essay to demonstrate there's been considerable and more focussed (though not necessarily better) writing on the topic since. And none of it is more relevant than Rock's?

"The Designer as Author" is overripe for reconsideration. But I would have greater respect for Dmitri's analyses if he looked at Michael Rock's output with the same rigor and skepticism he reflexively employs with, say, Emigre-associated products. What makes a weak criticism is the chumminess and gentility that suffuses the design profession. Before we start arguing specific theories to determine what graphic design is, we should take a honest look at who's being priviledged to put forth opinions. And that means doing much more than having a "Comments" section. Lux et veritas?

09.21.07

10:02

Elliott uses El Lissitzky's career to support the model of designer-as-artist; Dmitri uses El Lissitzky's Pelikan ads to support the supremacy of the designer/client relationship. In fact, El Lissitzky did a lot of work for Pelikan, some of it radical and innovative and some of it rather bluntly commercial. Some of the 'best' ads appeared in Kurt Schwitters's self-published magazine Merz, for which Lissitzky also provided occasional 'content.' Lissitzky published his own magazine in Berlin for a short time and he worked as a curator, writer, and lecturer. His self-published books are among the most influential design artifacts in history.

Like designers today, Lissitzky did some things for love, some things for money, and some things for both. Afflicted with TB for much of his life, he literally needed commercial work in order to survive, and survive he did. Unlike many of his legendary peers, he continued to work for the Stalinist regime across the 1930s, who supported him and his medical bills until the outbreak of WWII, when they let him go (and let him die).

Victor Margolin's moving and honest biography The Struggle for Utopia shows that this was no simple career. Lissitzky's life was full of ambivalence and compromise, just like that of any normal person.

09.22.07

07:43

So, question for Dmitri: where do you place Paul Elliman, dot dot dot, Dexter Sinister? and what about the artists whose work engages in what looks like design practice: Jorge Pardo, Andrea Zittel, Lawrence Weiner? Are these folks all dilettantes too?

As a design educator trying to define the field for the young'uns, I find the breadth I am trying to describe frustrating as well, so I turn to the classics, Charles Eames:

"Q: What are the boundaries of design?"

A: "What are the boundaries of problems?"

Gee, thanks!

09.22.07

10:55

"dilettante" is not exactly a compliment, so he consciously invited everyone to his party. he turned out to be an awfully quiet host. go figure.

it wasn't nasty, ellen. it felt real, uncensored, unsterilized and un-neutralized. i like that kind of "critical discourse". but that's just me.

"It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat."

-Theodore Roosevelt

"Citizenship in a Republic,"

Speech at the Sorbonne, Paris, April 23, 1910

09.22.07

04:47

This movie trailer is simply the lamest, most self-indulgent, hack-work that I've ever seen. Who would ever want to see this?

Oh, Eliott...you're sooooo creative. You've made music! Wow! Ooooo, you're well-rendered penises are sooooo....well rendered, too!

The fact that it's a bad movie I can deal with. Andy Warhol made some questionable films, as did many others. What I really am appalled by is that Earls holds a position of respect at CRANBROOK?? I mean, really. Would any student respect this schlock? He is an embarrassment to the students, staff, and alumni of this once fine institution.

Elliott, let's face it, is a jack-of-all-trades, who appears to have received too much positive reinforcement from his caregivers.

Time to face up to the truth: you're a tremendous bore. I suspected it years ago when I first became aware of your insipidly annoying Apollo project -- and it's confirmed now.

People, there's no need to intellectualize this garbage. It's just not design. Just because I water my lawn on the weekend does not justify adding "gardener" to my list of professional services.

As a criticism to the article's writer, there was no reason to waste you time writing such a long essay. This would have been best-suited as an blurb in the "Observed" column with minimal comment.

09.22.07

06:27

This is off topic so excuse the rant but this is a part of bloggery that really annoys me. I spend a couple weeks busting my ass to write something and then I'm supposed to babysit all the misinterpretations and ad hominem attacks?

There have been excellent comments on this thread, some of the best I've read on DO, (certainly some of the longest!) but honestly, I've kind of said what I have to say on the topic. It's your turn to type and my turn to read. Don't get in a huff because I don't jump in and repeat myself for your personal benefit.

As for Lorraine's direct question: Andrea Zittel and Jorge Pardo drive me even more crazy than Elliott Earls, but they aren't designers so I don't feel obliged (or qualified) to critique them. Their audience is the art world, their context is the gallery and I respect that division. If I were an art critic I might point out that art is overwhelmingly concerned with the personal narrative of the artist and various mythologies of the artist as heroic/tragic/domestic/etc. I might go on to say that while both Zittel and Pardo use the language of design, it is as primarily as a means of exploring their personal identity and building a visual record of their individual perspective. (At least so far). When they start making teapots for Target or all-over prints for Chanel then they will feel my wrath!

I think Dot Dot Dot is a dilettante handbook. That's why I contribute to it and that's why I read it. I could be wrong but I don't think Stuart Bailey (DDD, and Dexter Sinister) could be bothered to argue that his work is or isn't part of graphic design. He's quite adamant that he's not really interested in graphic design. He doesn't see a difference between design and art or doesn't care if there is one because it doesn't effect him. It still matters to me. I'm still effected by it.

09.22.07

06:43

Question 2: Why does Mr. Earls remind me so much of Ze Frank? And it's not because they happen to resemble one another (sort of).

09.22.07

07:28

The blogosphere is indeed a nasty, nasty place, but I don't see how this thread fits into the typical kind of knee-jerk, ad hoc nastiness of most blog discussions. Clearly there have been a few of those (Mr. Calling it like I see it for example), but by and large this has unquestionably been one of the most thought provoking high level threads I have ever witnessed on a blog. The typical nastiness and idiotistic threads on blogs are what generally keep me from reading them, but this one has been articulate and impassioned in a way that, contrary to Ms. Lupton's evaluation, has actually encouraged me to believe that perhaps the design world actually is capable of sustaining a critical discourse. Neutralized, antiseptic, and sterile discourse is precisely the kind of approach that IS NOT truly critical, agonal, or polemical. Journalism may take a falsely or pseudo-objective posture (falsely because all perspectives are subjective. And anyway neither subjective nor objective are in actuality any kind of superlative nor pejorative, but rather descriptive and categorical), and scientized academics may PREFER a sanitized arena of rhetorical "civility", but polemics and/or debate is by it's nature a CONTEST, to deny that is to deny Truth. In any polemical arena there are multiple perspectives in contest with one another, and some perspectives are certainly more valid than others, but it is the contentious arena of conflicting perspectives, in which any given perspective is tested and proved to be either worthy and valid or unworthy and invalid.

If the profession is indeed going to sustain a "critical discourse" then it must need be actually critical. True criticality may feel unfairly or unnecessarily aggressive, negative, or angry to the subcritical, but anyone that has ever subjected themselves to any kind of rigorous critique knows that critique is always harrying, painful, and difficult. But it is all these things because it is strenuously requiring one to bend and flex one's psyche analogous to the way strenuous physical exercise requires one to bend and flex one's body. If done correctly it builds and promotes psychic strength, flexibility, endurance, and health just like physical exercise. If done incorrectly it can pull, strain, or tear. But regardless, if it isn't painful it isn't working.

09.22.07

08:22

09.23.07

01:09

Too often the (for lack of better terms) "fringe" academics/practitioners feel the need to pick at any criticism that springs from "mainstream" critics/practitioners, and furthermore references any sources sprung from this well of supposed lock-step conformity of other mainstream "professional" practitioners. The most common way to do this is attack the research methodology, if not the mainstream critic's credentials.

As an educator, I look to the classroom as a laboratory for experimentation, inquiry, and outright contradiction to what might be happening in the so called design mainstream. I also look to my practice (and a more "mainstream" one than not) as a place to engage these ideas in a public arena, out of the often hermetic (if not navel gazing) world of academia and art practice. Maybe these ideas are diluted somewhat, but at least there is an attempt to test these notions outside the safety and comfort of the academy.

I identify with Mr. Stowell's elaboration on Mr Siegel's seed of wanting to be a designer that is simply "fascinated with the process of making things in collaboration with others and seeing how form and content can interact." Wanting to be a great designer in the traditional sense, and using this well-worn paradigm as a place to be expansive rather than "doing 'art design.'" I find it disheartening that so many posts here that claim to be defending the freedom to practice design in any way one wishes are so quick to dismiss (in some cases, rather mean-spiritedly) those critics who aren't making enough fringe or critical work (or whose prose isn't footnoted enough).