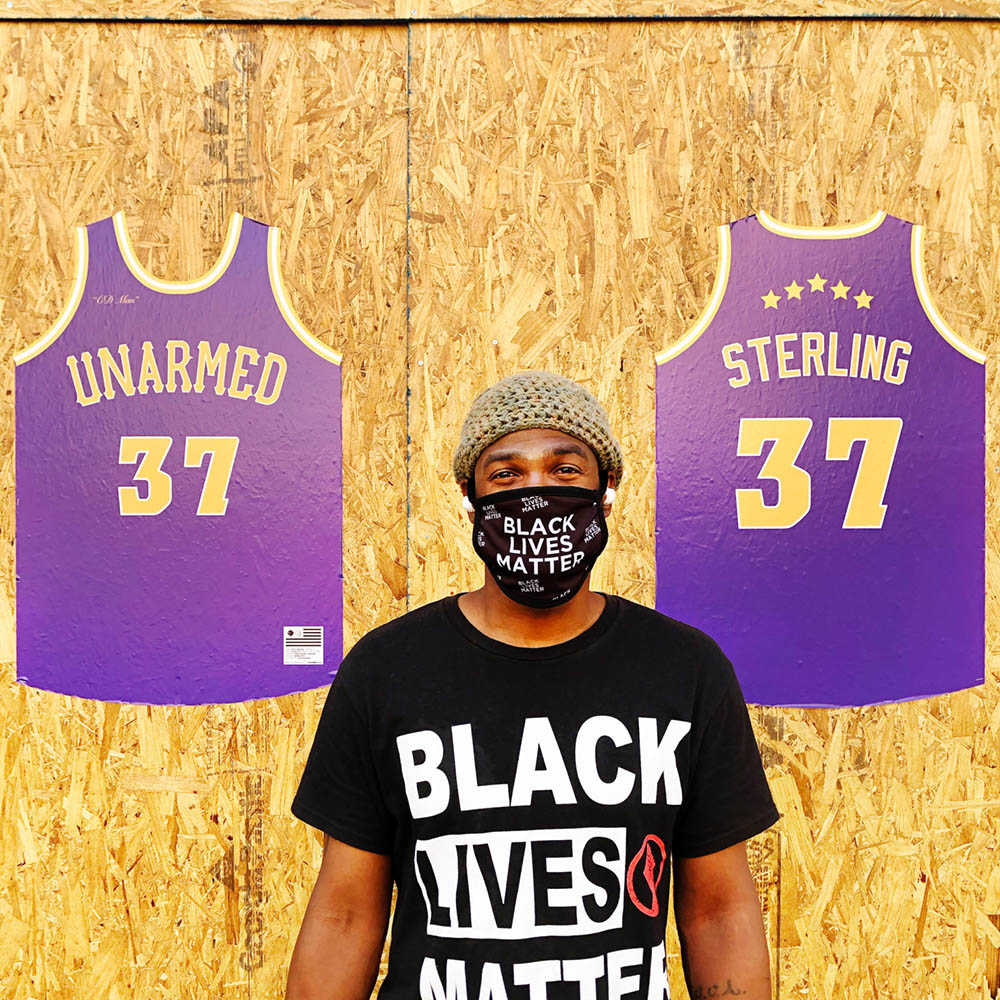

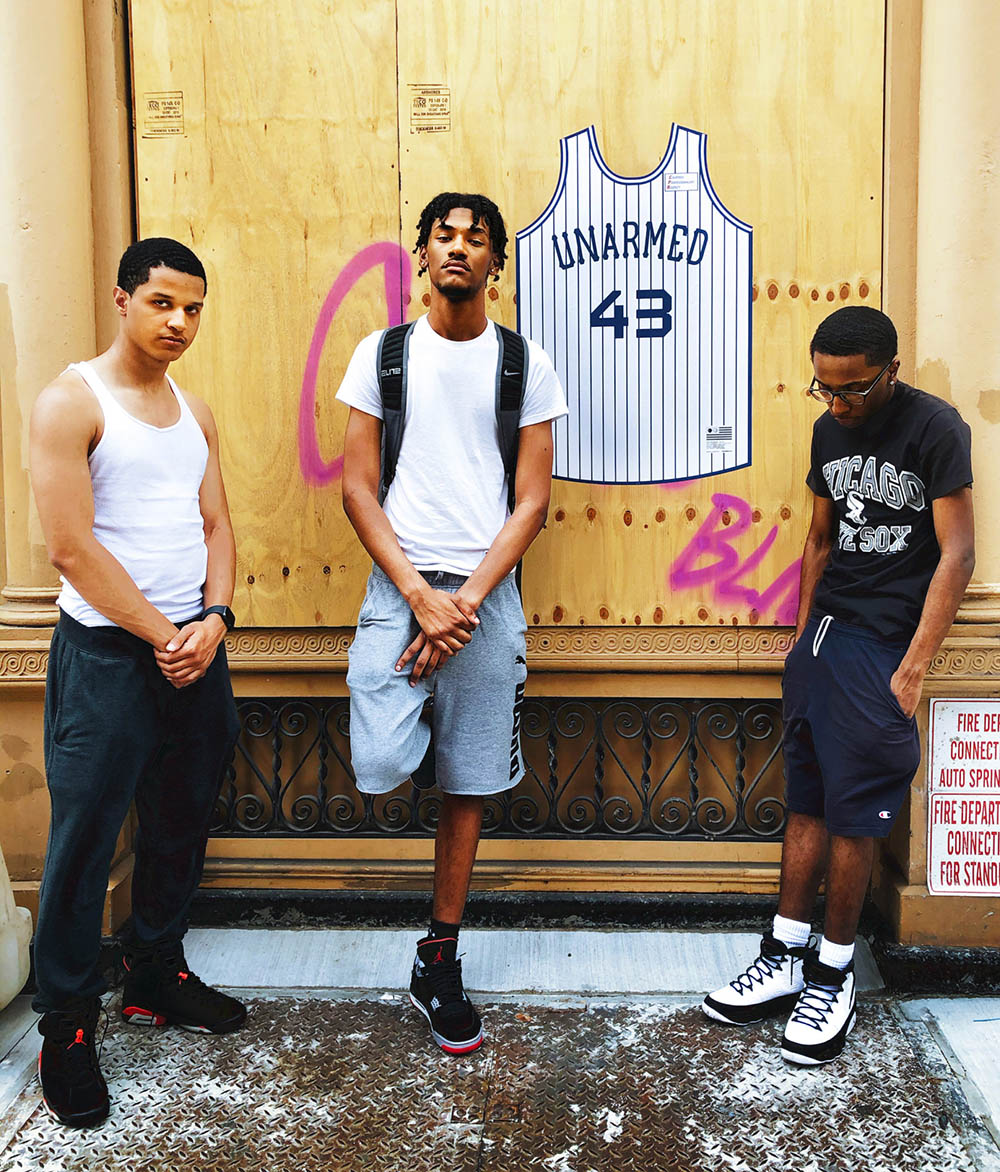

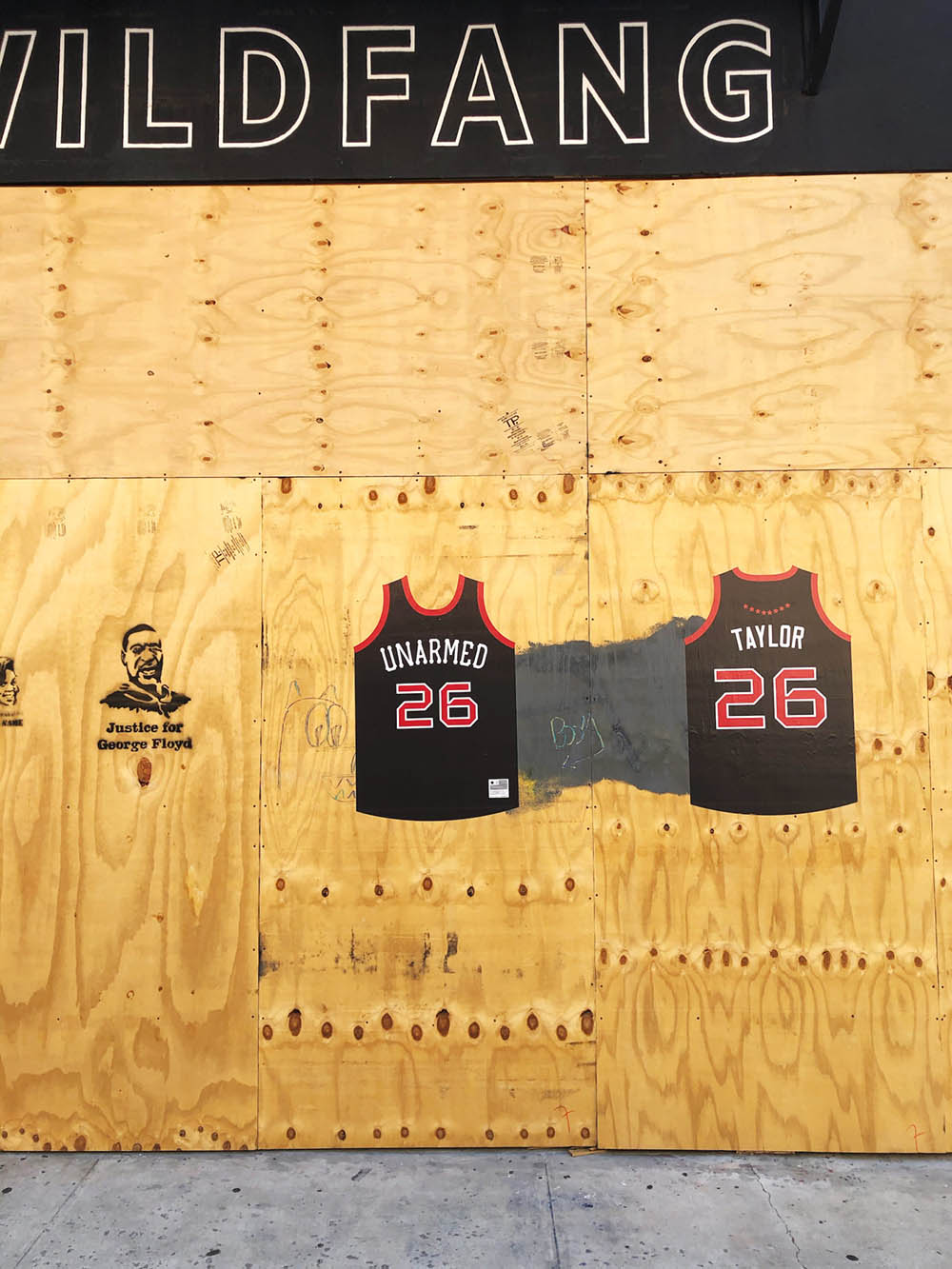

Since 2013, in the wake of the acquittal of Trayvon Martin's killer, the New York based photographer and filmmaker Raafi Rivero has designed a series of basketball jerseys with the team name “Unarmed.” Each jersey memorializes a victim of racist police violence and is in the color/brand of a nearby sports team. The victim's name is on the back of each jersey, the number is the victim's age, and stars, if present, indicate the number of times the victim was shot. “Unarmed” made its debut as a public art installation a couple weeks ago with a series of large-scale vinyl prints along the Flatbush Ave corridor near the Barclay's Center. Last weekend Rivero installed another run of jerseys in SoHo. Recently, I asked him to discuss the scope and outcome of the work. Here is his archive with documentation, all twelve designs, and media: http://unarmed.co.

Steven Heller: This is a powerful underscore of the growing and deadly racial divisions that continue to occur. How much longer is the campaign going on?

Raafi Rivero: “Unarmed” is my response to the question “what can I as a designer do to combat police brutality?” I’ve applied for a couple grants (one in the arts, one in the garment business) to help me continue with this project. I did receive the SBA’s small business loan and given that my actual field (commercial film production) is on hold (phase 4 in NY) may use some of the funds to continue with this project. An art gallery recently approached me about installing the series there as well. I have one more set of prints and am in touch with people in Oakland, CA or Ferguson, MO who’ve expressed interest in Unarmed, but no firm plans just yet.

I am making strides toward manufacturing physical garments and believe seeing people wear them will create striking images. At the moment I’m in touch with two manufacturers but nothing is set yet. If the jerseys make it to production then the goal is to donate half of the profits to family funds and social justice organizations, with the rest covering the materials and administrative costs of making them.

In short, I'm willing continue working on this so long as I have the emotional and financial bandwidth to press on. There are, however, no guarantees other than the one additional set of prints I have available.

SH: How has the response been?

RR: Overall I’ve gotten a very positive response: each time we installed the jerseys people immediately stopped to take pictures. One man stood by one of the prints for at least 15 minutes calling, texting, FaceTiming, live-streaming to social media. When we installed in SoHo several drivers honked and gave us the fist-pump salute or rolled down their windows to shout messages in support: “keep going!” “I love this” etc. People always ask if they can buy one. A post on Twitter — someone who saw the jerseys and uploaded some of her own pictures - got over 10k likes.

I’ve received a few negative messages as well. A (former?) friend left a series of angry comments and direct messages on Instagram which have since been purged from the service (not by me). In one of them he wrote that “[y]ou’re fighting an uphill battle.” — haha, ya think? And I’ve also received a handful of angry messages defending the police either as emails or direct messages on social media.

The series of prints that we posted on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn were vandalized, proving that angry racism exists even on the genteel border between Prospect Heights and Park Slope. Someone scrawled “CIA” and “they will kill us” on top of the prints in chalk. Someone else wrote BLM in spray paint below. It’s a live public conversation.

Five people have told me that they cried when looking at the jerseys - each person a different race or gender from the last — so the general response has been very positive. I think of it like when one cries in the movies — there’s a public grieving that’s built-in to the project.

SH: Are they only made in vinyl?

RR: On vinyl for now but lots of people have asked about and I certainly want to make them into actual garments. I’m actively looking for partners, expertise, and investment to help me do this now and have a couple people helping. We're in the process of sourcing; getting quotes from manufacturers.

SH: I know your inspiration and motivation but is there more to the story about making these?

RR: There’s been a lot of use of the word “ally” in the media these days and what it means to be an ally in the fight against racism. Two friends of mine, who are both white, were instrumental in getting this project off of social media and into public space. I posted the first jersey (Trayvon Martin) to my Twitter account in 2013 (it received no likes and one comment at the time). And Mike Brown to Instagram in 2014. Over the years the most common comment I’d get was something along the lines of “It makes me sad that you have to keep doing this.”

When I started, I didn’t realize that it was something that I could potentially be doing for the rest of my life. The emotional toll is the most difficult part.

It took me over a week after George Floyd’s murder to actually design the jersey. I’ve shed tears during the process for probably a third of the designs, including Floyd. After I posted it to Instagram a friend called to say that he and another friend talked it over, "we want to get this out there.” That was huge. Without them it would still be 2D files from Adobe Illustrator uploaded to social media. The fact that the friends who called me are white is significant to me personally, and also a perfect real-world example of the concept of ally-ship.

Speaking strictly in design terms I’ve done a lot of work over the past few weeks to clean up the actual design across the series. Going to print forced me to unify the typography of the word mark and numbers and do a lot of other nips and tucks. The project started out of pure emotion, but going to print has forced me to be a bit more rational. I started with a few sports fonts I downloaded from the internet but the most recent jersey (Rayshard Brooks) and all the ones that were printed on vinyl and installed have been refined, in some cases significantly, from the initial designs that were posted to the web.

SH: Are these jerseys part of a broader or wider action on your part?

RR: I’ve donated money to Black Lives Matter but that’s about it. I haven’t been to any of the protests (left NYC early on during Covid) but have returned twice to install the prints. I’ve participated in a number of marches over the years.

Police brutality has been a topic in my wider work as an artist. I wrote about stop and frisk for the NYTimes in 2013 (and created a Vine video which is now inaccessible on the Times site because the Vine service died — here it is on dropbox). A character in my film 72 Hours A Brooklyn Love Story? (Released 2018) wears early iterations of the Unarmed jerseys in every scene that he appears. (He’s wearing Oscar Grant at 1:29 in the trailer). The film was scheduled to have an outdoor screening sponsored by BAM this summer, but alas, Covid-19. The film features a scene where the characters are stopped and frisked.

raafirivero.com | thecolormachine.com