The very best of the covid-lockdown books I’ve read this Summer, is Harvard American history professor Jill Lepore’s The Secret History of Wonder Woman (Random House/Penguin, 2015). It is so much more than the origin story of the first feminist comics superhero and the biography of her polymath creator, the psychologist, lawyer, Hollywood consultant, scholar, pedagogue and charlatan, William Moulton Marston (who, among his life’s feats, invented the lie detector). Lepore chronicles Martson’s circle of feminist, suffragette, free-love, birth control-advocate friends and colleagues (including Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood, who is currently under scrutiny and “cancelled” for overt racism and her association with Eugenicism). It is a slice of little-known American history (the intersection of women’s rights and comic strip history) from the early twentieth century to the World War II years and the less explored role that “Wonder Woman,” launched in 1941, played in embodying the often-perilous movement for women’s rights in the U.S. and U.K. I have savored Lepore’s brilliantly insightful essays in the New Yorker on law, literature and politics. As though effortlessly she melds deep primary historical research with contemporary issues. This book does that too, through a feminist perspective imbedded within the legend of Princess Diana, the Amazonian crusader for democracy.

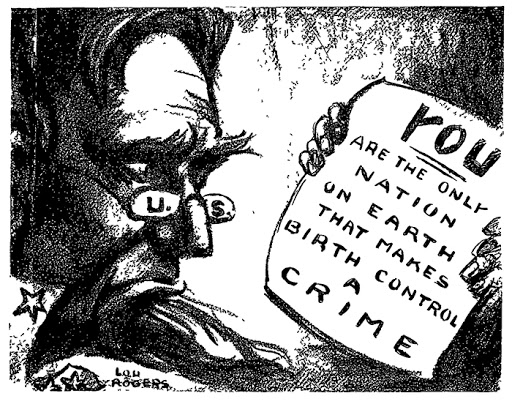

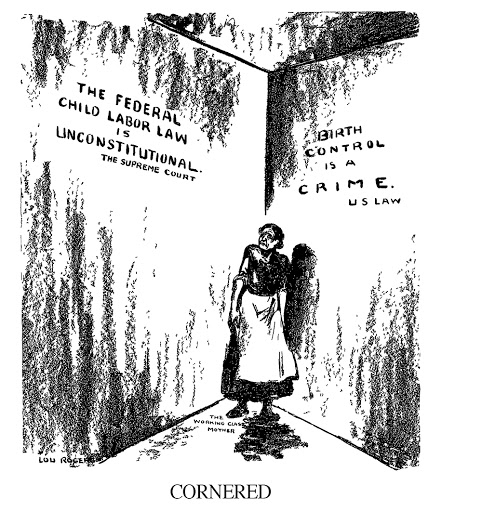

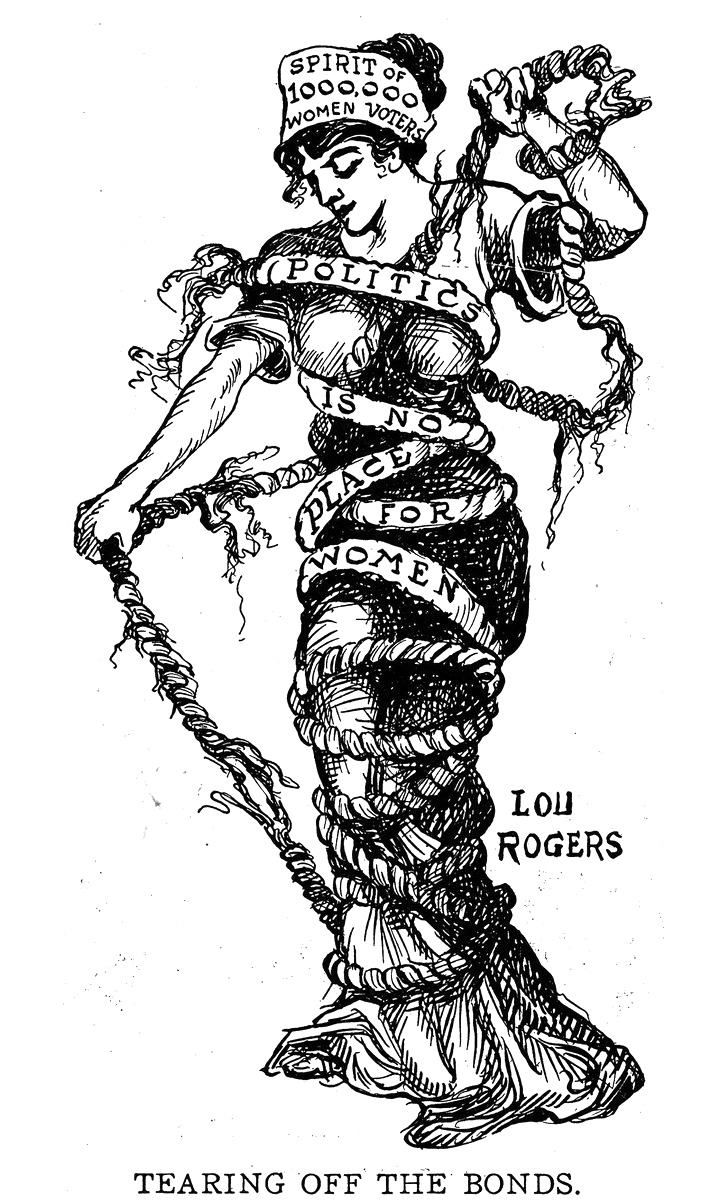

Arguably even more enlightening, Lepore also introduced me — as something of a side note in her book — to Annie Lucasta Rogers (1879-1952), a significant cartoonist for women’s suffrage and other injustices against women of her era (from about 1908-1940). Owing to gender-bias in the male dominated newspaper and magazine editorial industry, she used the nom de crayon Lou Rogers, in order to publish prodigiously as a visual commentator and caricaturist (The New York Call and Woman’s Journal the newspaper of the National American Woman Suffrage Association), editorial illustrator on woman’s rights (Judge magazine) and children’s book author. She was, furthermore, the art director of Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review where she published biting critical propaganda. Cartoons Magazine, a influential review of the world’s leading comic and satiric art and artists noted "Her pen is destined to win battles for the Woman's Movement and her name will be recorded when the history of the early days of the fight for equal rights is written." Cartoons featured many women in its pages, many of who are unknown today.

Rogers was an outspoken reformer, using her voice and body as weapons in the battles for the vote and other fundamental human rights that were denied women. She belonged to the Heterodoxy group of utopian and radical feminists whose militant protests were in the front line of liberation orthodoxy, often landing them in jail, suffering beatings from police.

In addition to her commitment to socialism, feminism and women’s liberation, long before 1960s, she earned a respectable reputation and varied clientele. Rogers wrote and illustrated a feature of children’s rhymes titled “Gimmicks” for the Ladies Home Journal. In the early 1930s she hosted an NBC radio program, “Animal News Club,” for which she designed the promotional poster and membership material.

She was by no means the only woman to create rousing agitational art. Others, even less recalled but no less worthy of respect today are Edwina Dumm, a long-time comic strip author-artist who eventually contributed her drawings to “Wonder Woman” comics. Cornelia Barnes, who contributed to Birth Control Review and (was a contributing editor for) The Masses. Then there was the incredible Blanche Ames, a botanical painter who produced editorial cartoons advocating the universal right to birth control. Away from the drawing board, she worked to reform women’s and children’s healthcare rights; and on top of that she was an inventor (Ames held patents for inventions which included a hexagonal lumber cutter and a method for entrapping enemy aircraft). Surprisingly, many other women were published in progressive periodicals like The Masses and The Liberator.

It may seem easy to get happily lost in the weeds of Lepore’s intricately researched The Secret History of Wonder Woman. Do not worry; she masterfully and artfully brings the reader back to her primary focus. Why, for instance, did Lou Rogers make an appearance, brief yet illuminating as it is? When she was working for Judge (which along with Puck and Life were the most popular social-humor periodicals off the times), she shared work space with Harry George Peter, who later was employed at Marsten’s studio in New York penciling “Wonder Woman” stories, covers, and strips and inked in the main figures (assisted by various of female artists who did background inking). Lepore’s digressions not only never lead the reader astray but rather enjoyably and intelligently connect the imperceptible dots.