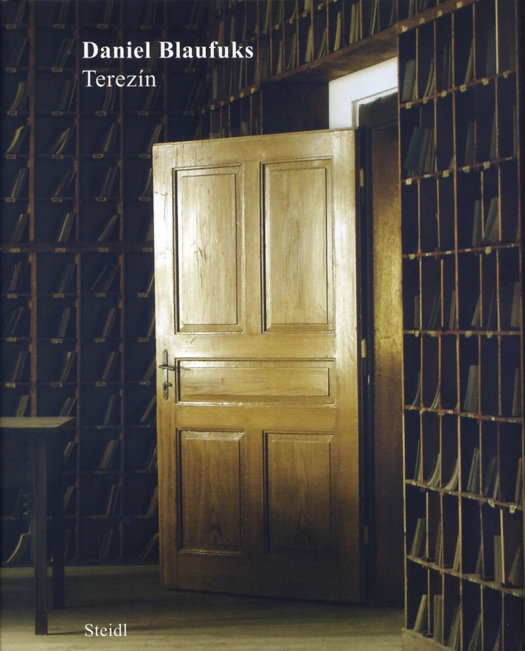

Daniel Blaufuks, Terezín, book cover, Steidl, 2010

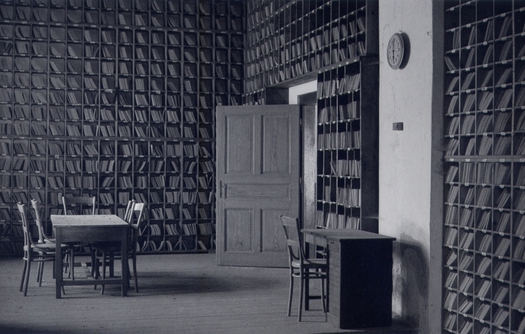

In a post about W.G. Sebald’s use of pictures, I reproduced a spread from his novel Austerlitz, showing a room with a grid of shelves from floor to ceiling — the records room at the Terezín concentration camp, the so-called Small Fortress, located about an hour from Prague. I was sure I had encountered the picture somewhere else, but the source didn’t spring to mind and the immediate focus of my essay lay elsewhere so I didn’t pursue it.

A couple of weeks ago, I happened to see Daniel Blaufuks’ book Terezín, which was published last year, and there on the cover was a color photograph of the same room. Leafing through, I found that Blaufuks, a Portuguese photographer and artist, was haunted by the picture, which had become the starting point for a multilayered work of image, text and video suffused with its own Sebaldian melancholy. Blaufuks imagines Melville’s Bartleby entering the room and declaiming his famous protest: “I would prefer not to.” He considered writing to Sebald or his editor about the picture, but never did so (Sebald died in 2001).

In the novel, Sebald has the eponymous Austerlitz claim to have come across a large-format photograph of the shelf-lined room in an American architectural magazine (sadly unspecified) and he is quite clear that this image documents the place “where the files on the prisoners in the little fortress of Terezín, as it is called, are kept today.” Austerlitz regrets that he didn’t visit the Small Fortress to pursue his investigations when he had the chance. One then turns the page to discover the picture.

W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz, Penguin, 2002

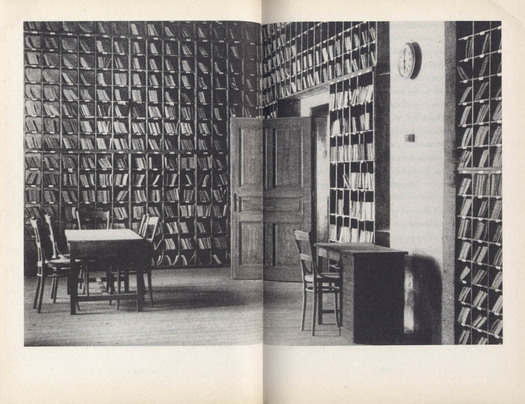

The black-and-white photograph is grainy and degraded, making it look like it might even date from the Second World War, and there is no credit of any kind in my UK edition. But it is unwise with Sebald to take anything for granted and his habit of photocopying his source material to roughen it up could easily have created this effect. In his book, Blaufuks wonders whether, “this was a real space or a staged one, an old photograph, which Sebald had found in some archive or one he himself had taken.” It was to answer this kind of question in relation to the Antikos Bazar that I had undertaken my own trip to Terezín in 2004. Blaufuks shows the spread in his book, though he is working from a different edition, where the picture is awkwardly broken into two panels across the inside margins.

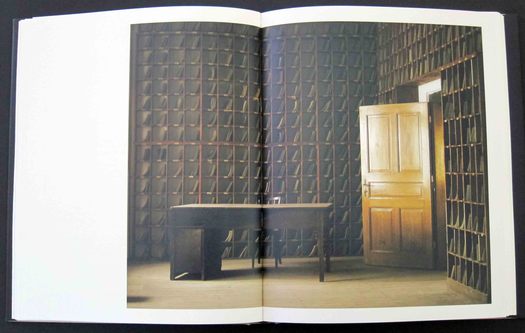

In 2007, Blaufuks’ obsession also takes him to Terezín — to the Small Fortress, where he quickly finds the room. But it isn’t possible to enter the building through the doorway that says Geschäftszimmer (office) and he peers through the window from the courtyard, from the same angle that he decides Sebald must also have seen the room, “as this was the exact point of view of the photograph in his book” — this is to assume, of course, that Sebald took the picture. Then, turning the page, one finds Blaufuk’s color photograph of the room, looking just as much like a stage set waiting for someone to enter as the empty room in Sebald’s novel, except that the furniture has changed, there are fewer files more precisely organized in their cubbyholes, and Blaufuk has omitted the clock with its hands set exactly at six o’clock. Oddly, for someone who has studied the room so closely, he cannot remember whether the clock was still there at the time of his visit. If he took this picture from the courtyard through the bars and the windowpane, as he implies he did, the results are spectacularly good.

Daniel Blaufuks, Terezín, 2010

I should add that although I paid a brief visit to the Small Fortress at the end of my day in the town, I wasn’t looking for this unenterable chamber and I didn’t see it through the window, though I have my own Sebaldian regrets about that now. But I have no doubt that the room exists, as this (clockless) picture on a Czech news website confirms; and what a demystifying shot it is — the impact of both the Sebald image and Blaufuks’ picture depends on the grid of shelves filling the picture frame as if these infernal records go on forever, detailing with a cold bureaucratic formality completely at odds with the murderous truth, the passage and elimination of so many lives. In the news photo, which shows the same arrangement as Blaufuks’ shot, we see the humdrum reality of the office.

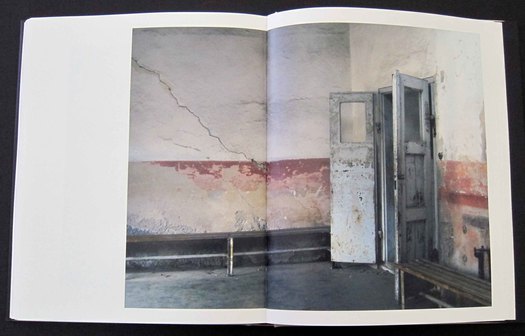

During my visit in 2004, I took a few pictures, but I didn’t feel I had a good enough reason to be doing it and stopped; the morbid visual souvenirs of this kind of horrors-of-history tourism are always dubious. After looking at Blaufuks' pictures in Terezín, I returned to my handful of photos this week and found one moment, with the subject once again doors, where our viewpoints had closely coincided, as we made our ways around the Small Fortress.

Daniel Blaufuks, Terezín, 2010

Rick Poynor, Small Fortress, Terezín, 2004

Not until the copyright page at the back of Terezín do we learn the source of Sebald’s mysterious picture of the room. Blaufuks discovered this shortly before the book went to press, in his publisher Steidl’s library, and says it completes a “perfect circle.” I could have kicked myself when I read in his brief note that the photograph appears in a section on Terezín in the late German photographer Dirk Reinartz’s Deathly Still: Pictures of Concentration Camps. In 1996, on a visit to Zurich, the book’s publisher invited me to take a book and I chose a copy of this brilliantly conceived and profoundly unsettling volume, based on photographs taken between 1987 and 1993. It had been a long time since I looked at Deathly Still, but that was where I had seen the picture. And, with Sebald studies now a small industry, at least one scholar has gone public with the source, in a footnote — not exactly a billboard, I grant you — in the study W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity (2007).

Dirk Reinartz, Small Fortress, Terezín from Deathly Still, Scalo, 1995

So the lugubrious artificer of hybrid fictions delivers another sleight of hand. What else would we expect?

Comments [11]

Thanks so much for the article. Like many (I hope, I wonder) I am what can only, and should only be called, a Sebald fanatic. And relish all such industrious studies as this one. Remembering (perhaps with less flare as Sebald) that it took three tries to finish my first Sebald book, The Rings Of Saturn, picked up, bought for reasons I can not remember. But only one try to finish all the rest.

06.22.11

08:58

Before your investigations the image was a palimpsest, with all the ambiguity that implies. It was rubbed clean of its origins. But it was still (if not more so) just as powerful in its new, re-purposed, context.

Are there any other writers who have as much visual dexterity?

Sebald used photography not for illustration but as a kind of parallel text. This essay brilliantly parsed the image just as if it was a close reading a poem. Thanks.

06.23.11

09:04

thanks for the beautiful text. i did shoot the image through the window glass and bars, I was never inside the room...

06.23.11

01:33

To answer Adam's question, I tend to think that Sebald is in a class of his own as a novelist when it comes to his visual dexterity, but there are certainly other writers who have worked with embedded photography, if only in single texts.

A consistently rewarding site for discussion of the visual aspects of Sebald's work is Vertigo written by Terence (Terry) Pitts, executive director of the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Iowa.

At LibraryThing, under the name VertigoTwo, he has compiled a handy list of more than 100 books with embedded photographs, from André Breton's Nadja to Jonathan Safran Foer's Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

Select VertigoTwo's viewing style to see his additional comments about the use of photography in the books.

06.23.11

03:09

Likewise his cropping on the bottom, to lose the little triangle of light that defines the dark space of the side of the desk under the clock. It's so much more ominous in Sebald's.

06.24.11

09:42

The highlights in the Sebald image are another aspect of its greater immediacy. Light has appeared in the image where it barely seems present in the source: Sebald’s files in their cubbyholes possess far greater definition than the files in Reinartz’s more evenly toned original.

06.24.11

10:30

http://www.antwerpcentral.be/

i was in the city last month, and spent part of an afternoon poking around the station, which is extraordinary, and has been renovated dramatically since the book came out (i've written about this here in the past). i sat down for a drink under the grand clock in the cafe, which is expensive but worth it, and kept an eye out for a man with a rucksack while thinking about the concepts of time and travel and memory.

06.24.11

12:04

06.24.11

03:37

The DVD that comes with Daniel Blaufuks' book is another reason to take a look at this project. In the novel, Austerlitz studies the surviving fragments of a staged Nazi propaganda film (long mistitled The Führer Gives a Town to the Jews) that was intended to show that life was good in Theresienstadt — the German name for Terezín. Looking for his lost mother, Austerlitz imagines he has found her in the image of a young woman attending a concert. In a similar way, Blaufuks combs through the footage for a person named Ernst K, whose diaries came into his possession, and who also, he tells us, ended up in Theresienstadt.

Blaufuks intensifies the grossly misleading holiday camp-like scenes of apparently happy occupants by tinting them red and slowing them down, including the voiceover, which becomes diabolical.

06.26.11

07:45

06.26.11

10:24

05.18.12

06:47