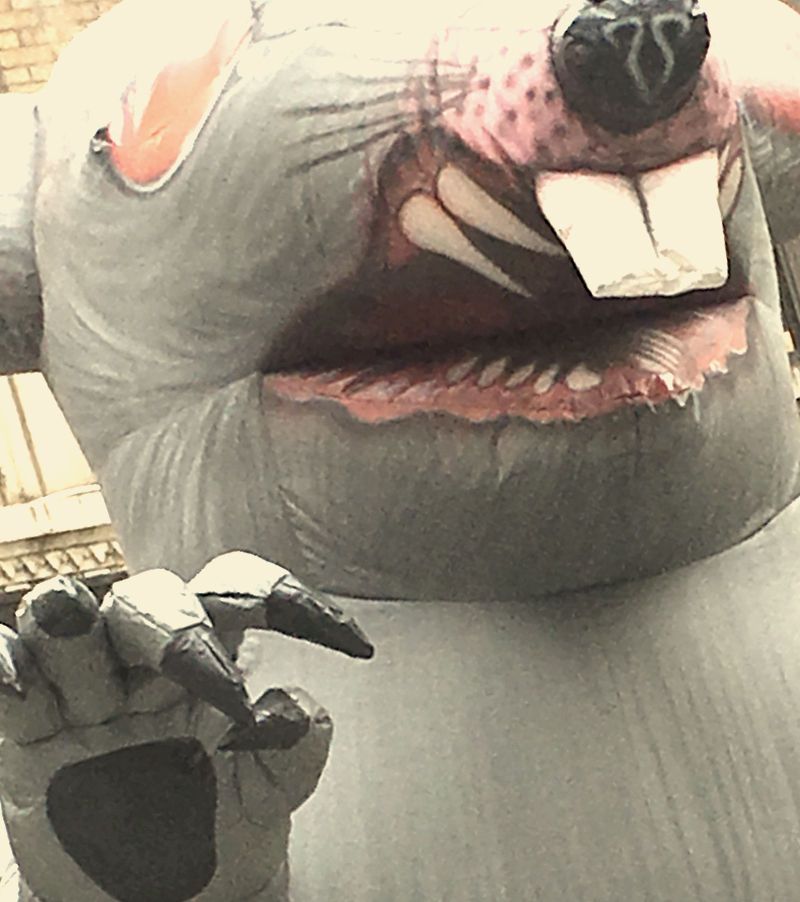

If you are already repulsed by New York’s undesireable rat population, the huge “union rats” menacingly propped up on sidewalks and flatbed trucks in front of construction sites and office buildings, will not make you feel any warmer towards the smaller variety. The grotesque 25 foot tall “union rat” or “Scabby,” as it is appropriately nick-named, is the labor movement’s most effective protest icon and guaranteed to grab the attention of even the most blasé passersby. Tethered to rumbling portable generators, these inflatable rubber rodents are designed to be even more unpleasant than the real things, if that is possible. They reek with the stench of dirty rubber yet send a message in seconds that would take a picket line of chanting, sign-carrying protesters considerable time to achieve.

Scabbys do not carry disease, but they do instill guilt. They are an instantaneously effective way to announce to passersby that wherever they are perched, the facing jobsite, factory, or restaurant is infested with non-union labor. Now that President Trump has promised to bring work back to Americans, these humongous inflatable vermin, replete with horrid buck teeth and sharp incisors, have acquired even greater relevance as a political weapon. Without putting too sharp a point on it, the Nazis used vermin as a metaphor to describe what they believed were parasitic Jews and other foreigners in Germany. New Yorkers have not been exposed to the same constant barrage of propaganda, but we understand in word and picture that an urban rat comes with negative baggage.

Most New Yorkers are nauseated when real rats dart from under trash bins or sprint along the subway tracks, likewise these rubber blow-ups are imbued with a je n’cest qua repulsiveness. There have been other dimensional protest symbols and effigies over the past decades, but the inspiration for the Scabby emerged in 1990 when the Chicago Bricklayers union ordered the first specimen. It was made with a distended stomach covered with puss-filled globules. The nightmarish eyesores, designed and manufactured by Big Sky Balloons in Illinois, come in 12 and 25-foot versions and are reminders of a time when organized labor had more power than it does today, and mass demonstrations of striking laborers had considerable impact.

With unions on the decline, disgruntled union members are not only reduced in numbers, but picketing is strictly regulated by city ordinances, and don’t do a lot of good. To use Scabbys or similar inflatables, permits must also be obtained, but demand less person power. And the introduction almost three decades ago has had an impact on popular perception. Matt Soniak, a writer for Mentalfloss.com, noted that since 1990 Scabbys, which cost about $8,000 each, have infested the East Coast cities in ever larger numbers.

Inflatables have a long history. Not only as balloons in the Thanksgiving Day parade, or as retail displays especially on used car lots, but for protest. In 1968 the anti-establishment underground paper I art directed, The New York Free Press, hired a cause-based PR firm to build a mammoth termite intended to take metaphorical big bites out of City Hall. Symbolically, it might have worked, but the prank was foiled by lack of necessary permits for marching through the city with large, airborne insects and, in any case, the poor quality of the workmanship caused the thing to deflate before its first bite. A few years ago Stefan Sagmeister created a set of inflatable charts and graphs to show tax allocations for health versus armament for Business Leaders for Sensible Priorities, along with a 20 foot tall inflatable baby to show infant mortality rates. Scabbys are not the only inflatable protest symbols, but they’re not just hot air. They brilliantly express anger and frustration, and vividly illustrate unsavory dealings, giving dimension to James Cagney’s famous line: “You double crossing dirty rat.”