The design of infographics has always been an exacting art, so imagine trying to explain the human body, for example, in medieval times. This week, I went back to the sixteenth century and worked my way forward in time exploring anatomy drawings by a variety of artists, woodcutters, and engravers. In the process I found one name we are all sure to know, Albrecht Dürer.

The history of human autopsy and dissection is long and complicated. Early Roman law forbade it, Christian Europe tolerated it, and yet the Catholic Church in 1533 ordered the dissection of conjoined twins Joana and Melchiora Ballestero to determine whether they shared a soul. What they discovered were two separate hearts—hence two souls.

All of these illustrations are looked at today and understood differently by the viewer. Artists and designers see charm of line, color, or style; medical doctors see the science of it all the while remembering their first anatomy class; and historians may connect the political situations to the time and place they were made.

These illustrations (and many more) were discovered on the website maintained by The History of Medicine Division, of the U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health.

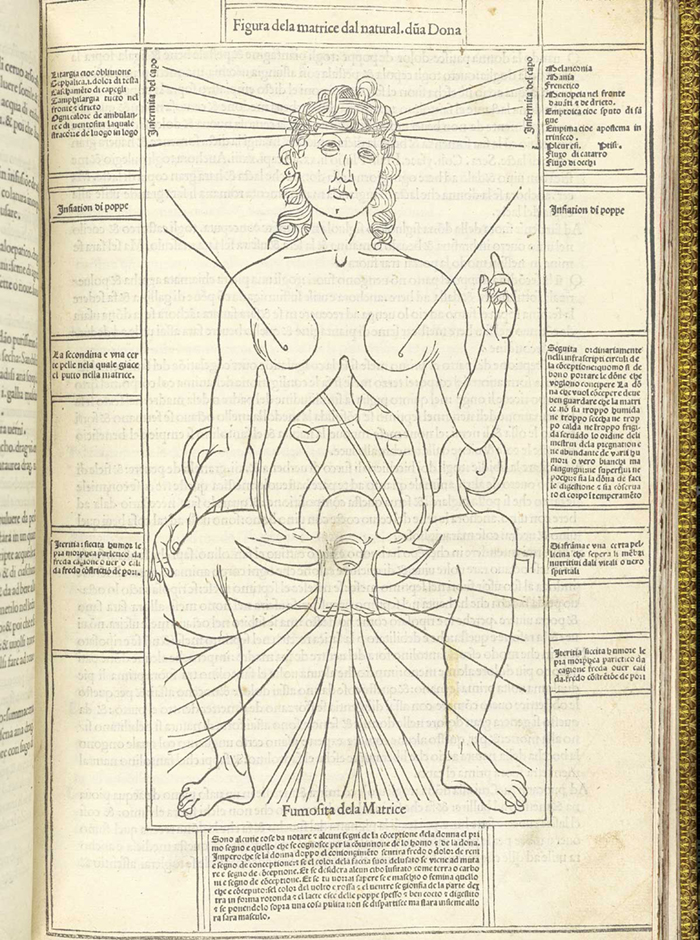

Johannes de Ketham | Fasciculus medicinae | 1494

Johannes de Ketham was a German physician living in Italy at the end of the fifteenth century. Little is known about him, but he has been identified by many as a physician practicing in Vienna in 1460 named Johannes von Kirchheim. Fasciculus medicinae was the first printed book to contain anatomical illustrations.

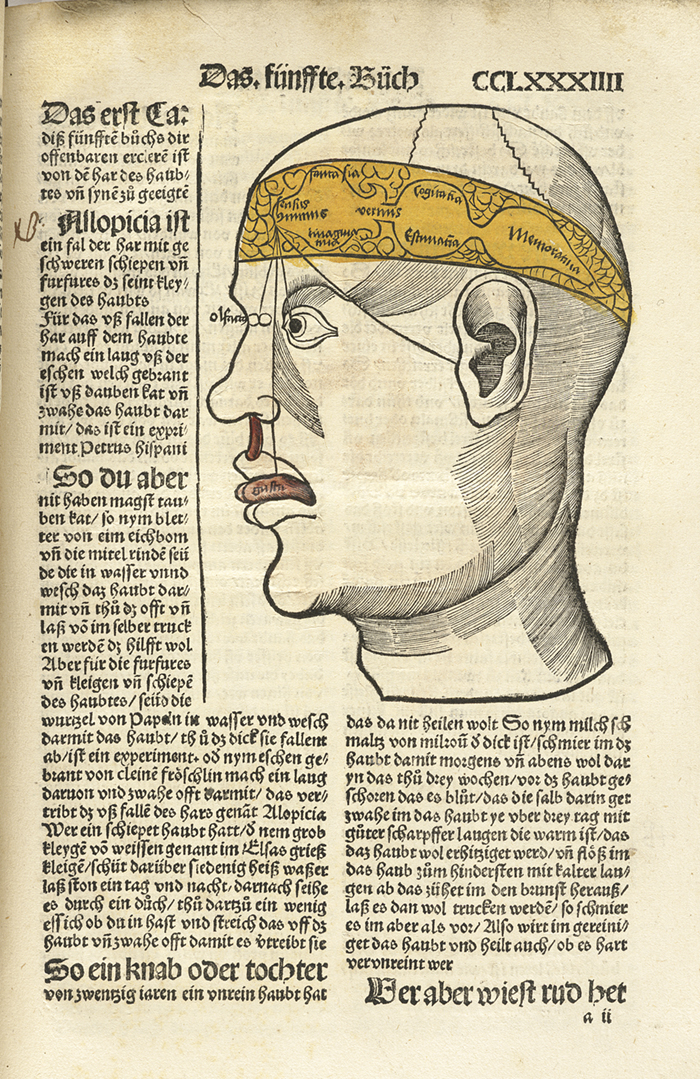

Hieronymous Brunschwig | Liber de Arte Distillandi | c. 1450 to 1512

Hieronymous Brunschwig | Liber de Arte Distillandi | c. 1450 to 1512

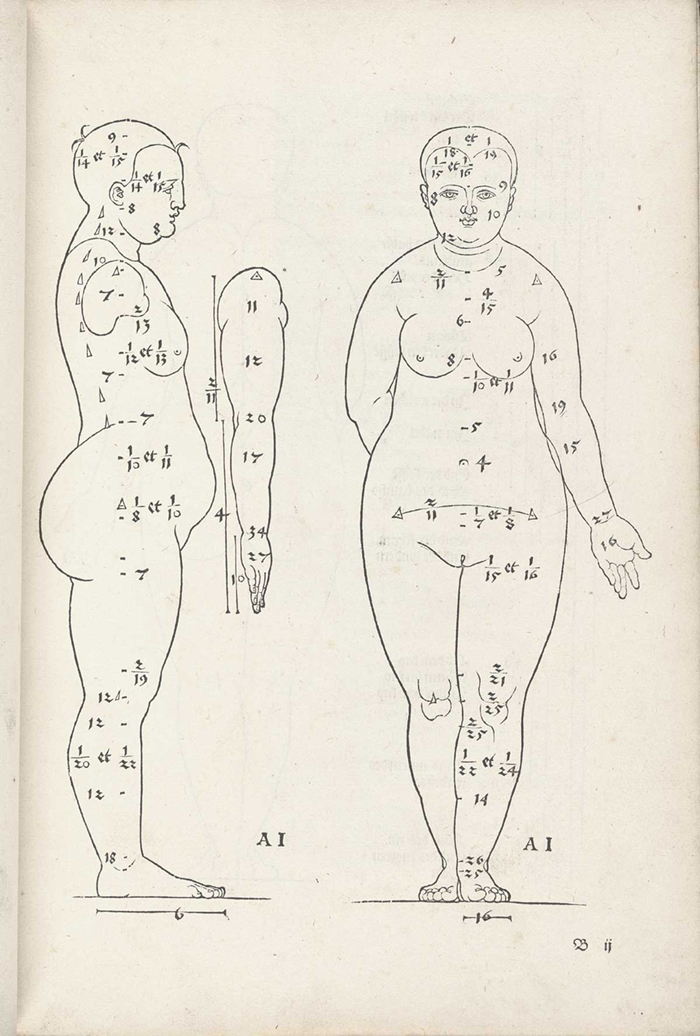

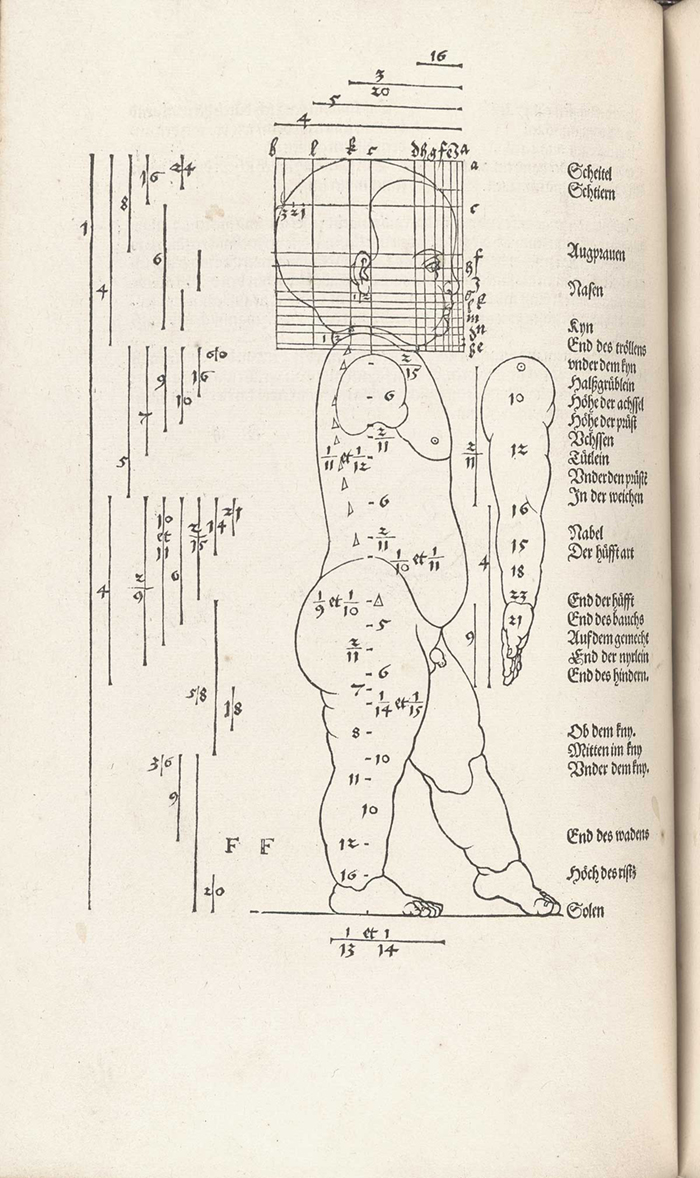

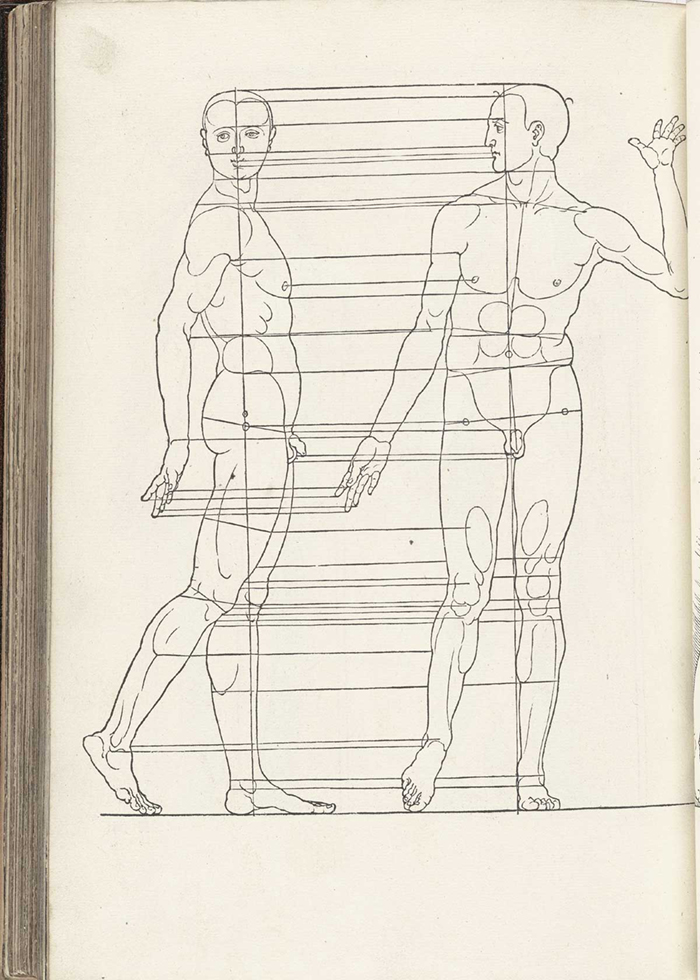

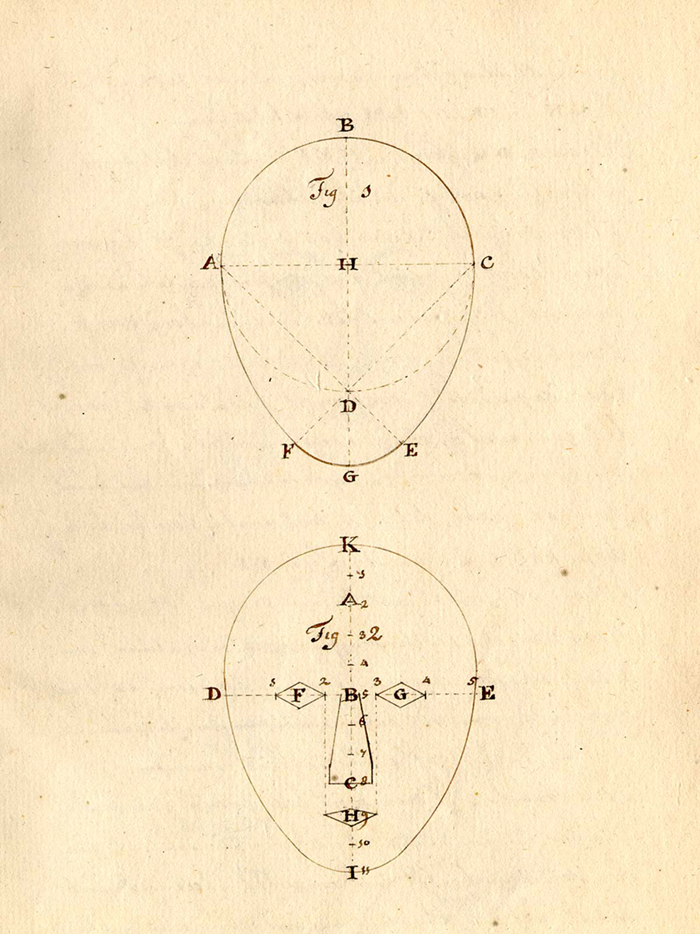

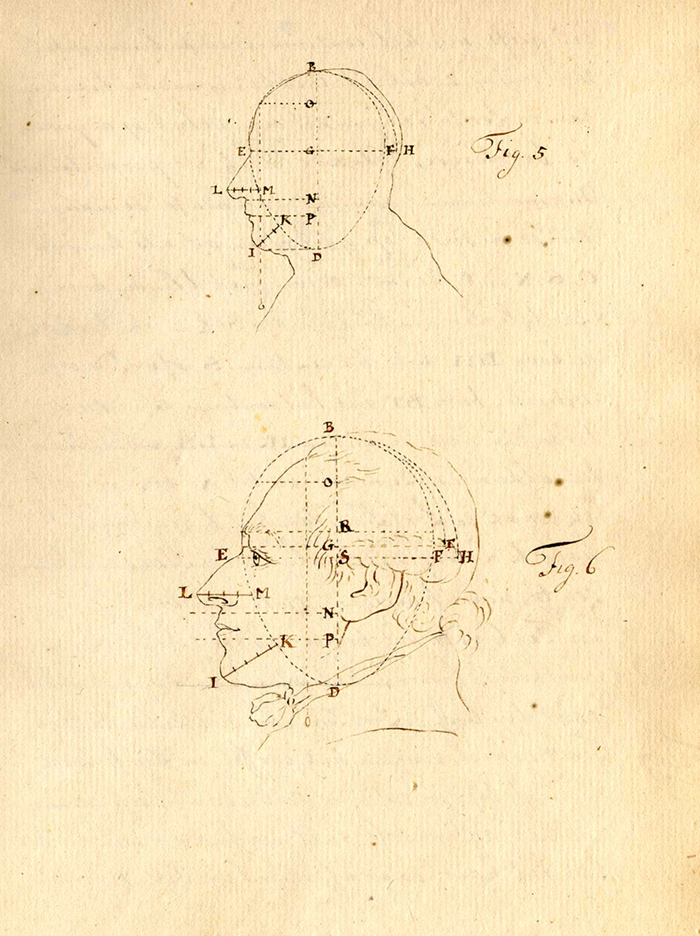

Albrecht Dürer | Vier Bücher von menschlicher (Proportion) | 1528

Dürer's Proportion was written, designed and edited by the artist himself and is the first published attempt to apply the science of human anatomical proportions to aesthetics. It is divided into four parts: the first two parts discuss the proper proportions of the human form, the third part adjusts the proportions using mathematical rules, with examples of extremely fat and thin bodies, and the fourth shows the human figure in motion.

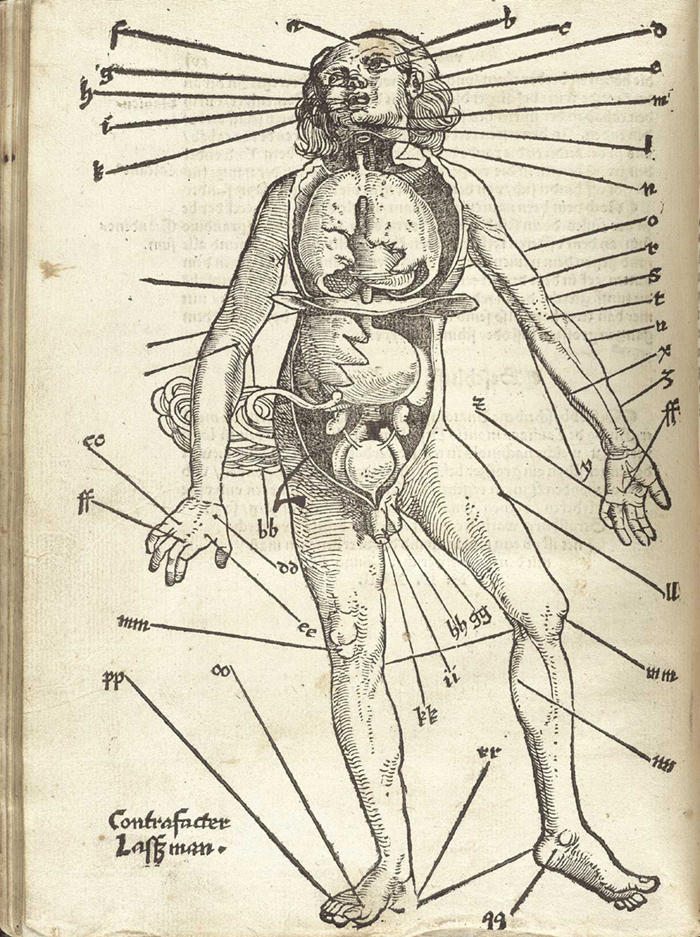

Hans von Gersdorff | Feldtbůch der Wundartzney, or Fieldbook of Surgery (i.e., “Wound Doctoring”) | 1528

The Feldbůch contains four woodcut anatomical images, including a bloodletting figure (with internal organs exposed), “Wound Man,” a skeleton, and another figure showing internal organs (the “viscera-manikin”). Virtually nothing is known about the illustrator, Johann Ulrich Wechtlin, also known as The Master of the Crossed Pilgrim’s Staves (Maître aux bourdons croisés).

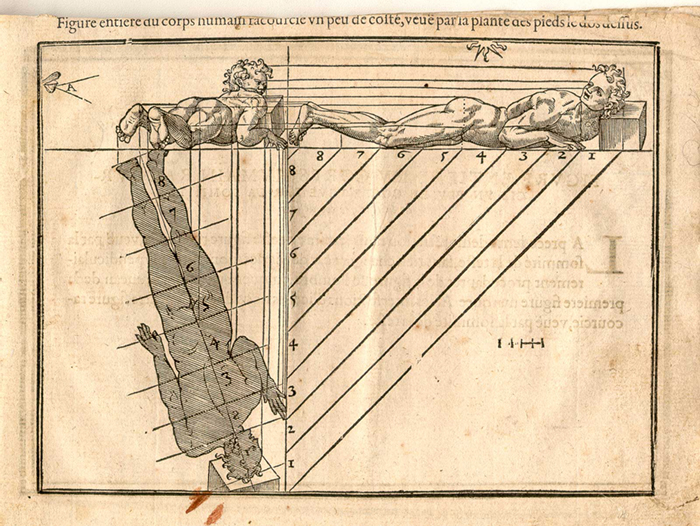

Jehan Cousin | Livre de pourtraiture | Paris 1608

This book is one of the most famous on the subject of artistic anatomy and was printed again and again into the late seventeenth century.

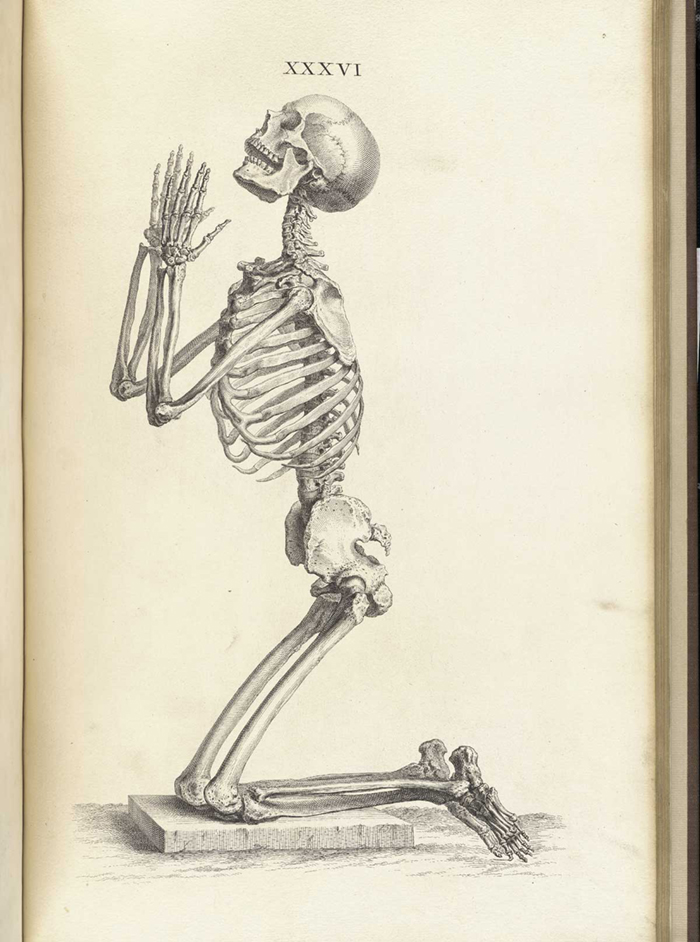

William Cheselden | Osteographia, or The Anatomy of the Bones | 1733

In 1733, William Chesleden published Osteographia, a grand folio edition depicting human and animal bones, featuring beautiful copperplate images, including playful skeletons, vignettes, and initials. He depicts all the bones of the human body separately in their actual life size “and again reduced in order to shew them united to one another.” Cheselden and his engravers, Gerard van der Gucht and Mr. Shinevoet, employed a camera obscura to execute many of the images, and the practice is depicted in the title page vignette. The work, which was most likely printed for Cheselden by William Bowyer, was unfortunately a financial failure, as his bid for subscribers was met “with little success,” which was the case with so many large anatomical atlases of the period.

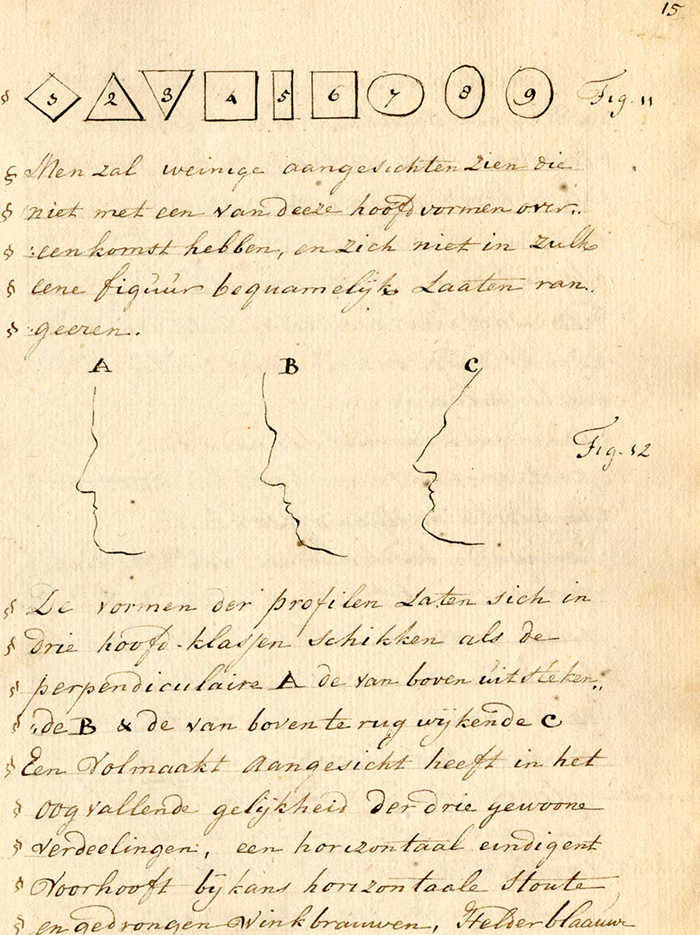

Anonymous | Treatise on physiognomy | Netherlands, ca. 1790.

The author of these images, (manuscript, treatise, and sketchbook) on physiognomy is unknown. The text is written in Dutch and was probably composed in the 1790s. It is possible that these drawings were created for a dissertation by a medical student.

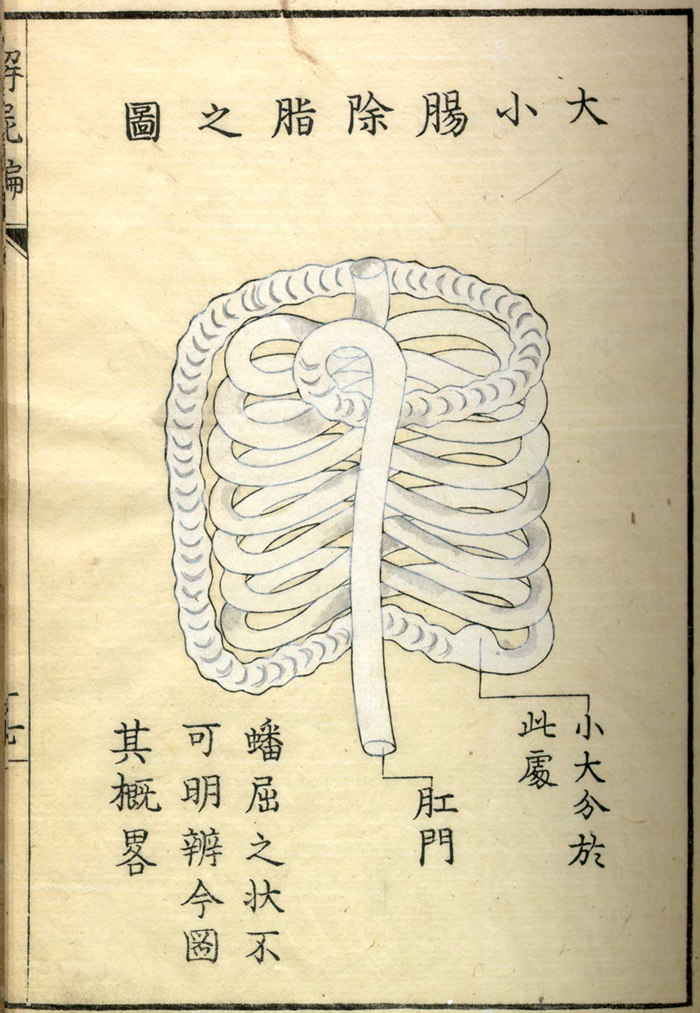

Kawaguchi Shinnin [or Nobutada] Shien cho (Complete Notes on the Dissection of Cadevers) | 1802

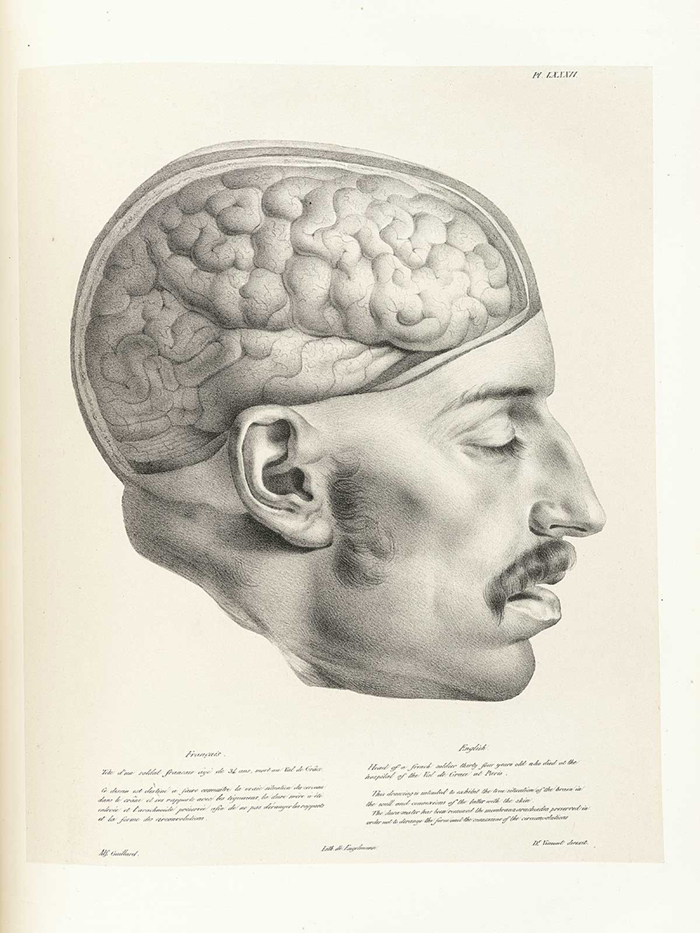

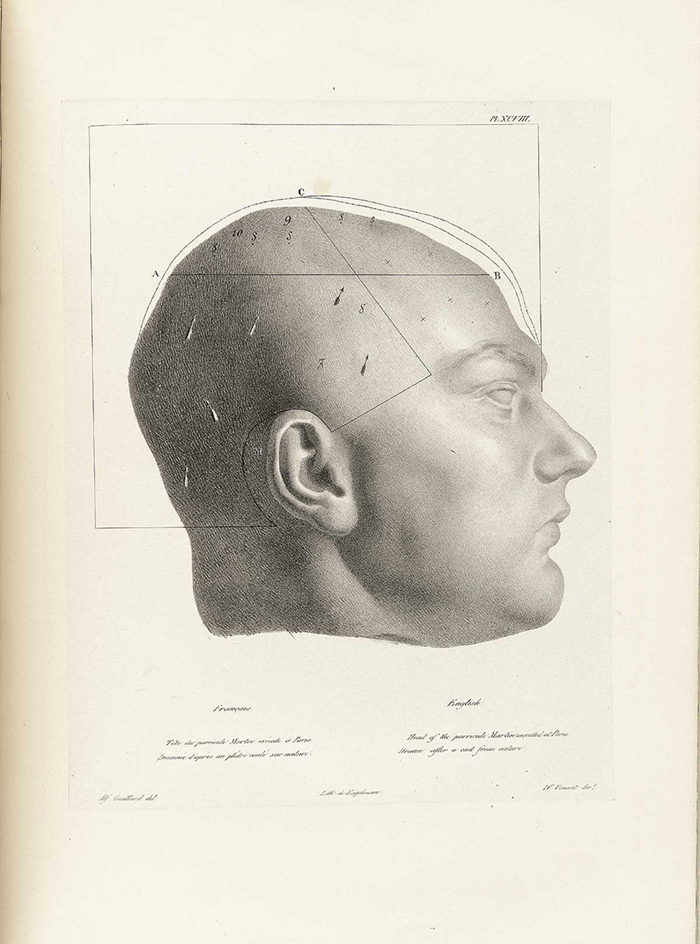

These three illustrations are selected from part of a large group of 133, executed by a number of artists and lithographed by the noted Godefroy Engelmann. The publisher, J. B. Baillière, with offices in Paris and London, was a champion of phrenology and was responsible for disseminating most of the important French publications in the field in the 1830s and 1840s.

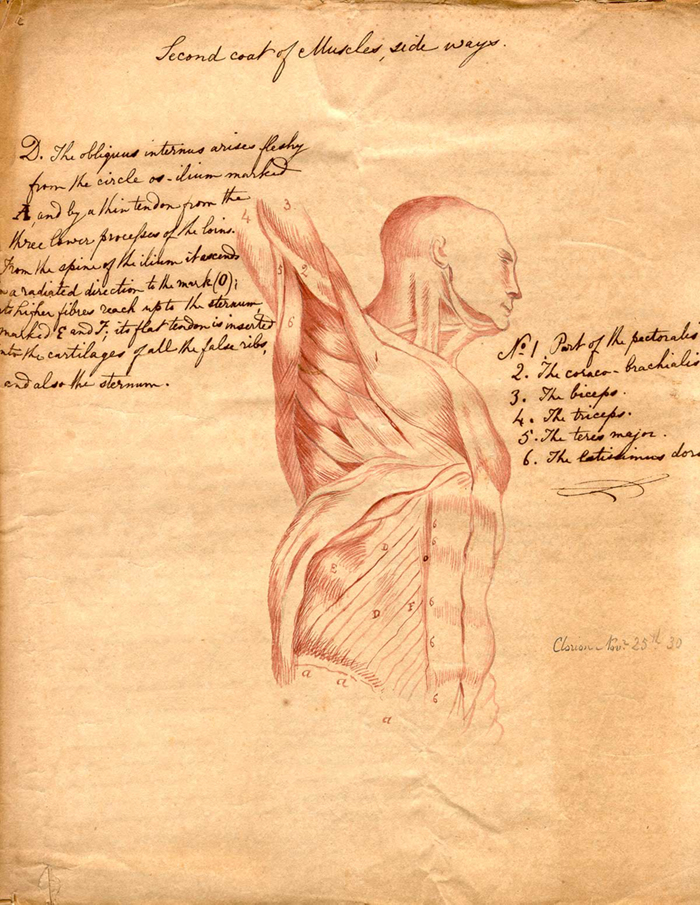

Clorion | Anatomical illustrations | 1830

“Clorion” was a pseudonym used by the creator of this anatomical sketchbook in 1830. It was apparently copied from The Medical Adviser and Domestic Physician, possibly a journal, published in London in 1830; unfortunately, no extant copies of the printed version can be located.

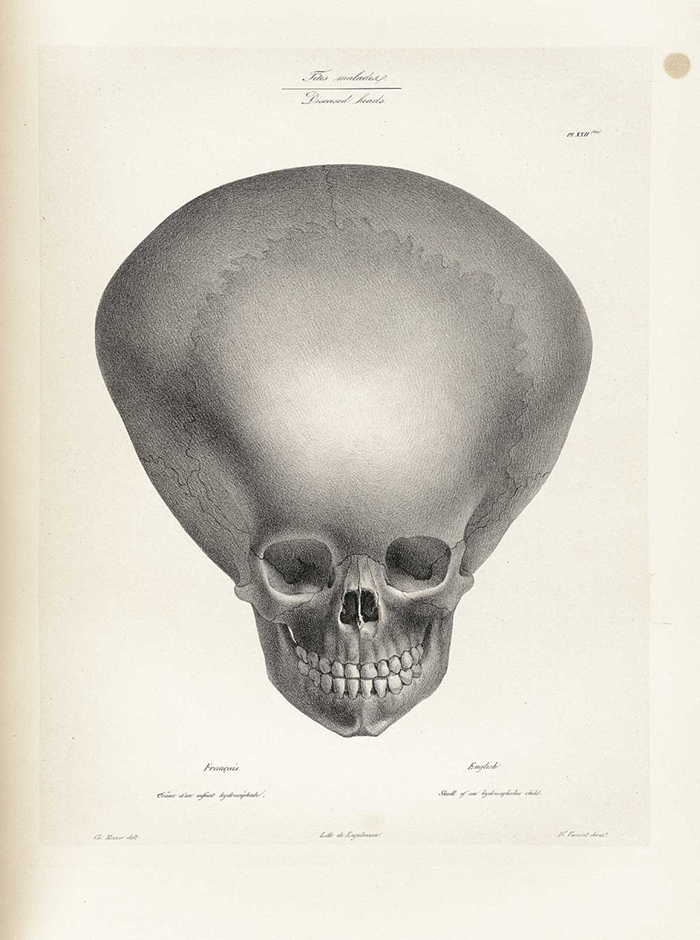

Joseph Vimont | Traité de phrénologie humaine et comparée | 1832–35).

Joseph Vimont was born in Caen, France, in 1795. He attended the Faculté de medicine de Paris, from which he graduated in 1818 with a dissertation on ophthalmia. Little else is known of his career with the exception of his publication of the magnificent Traité de phrénologie humaine et comparée from 1832 to 1835. He died in 1857.

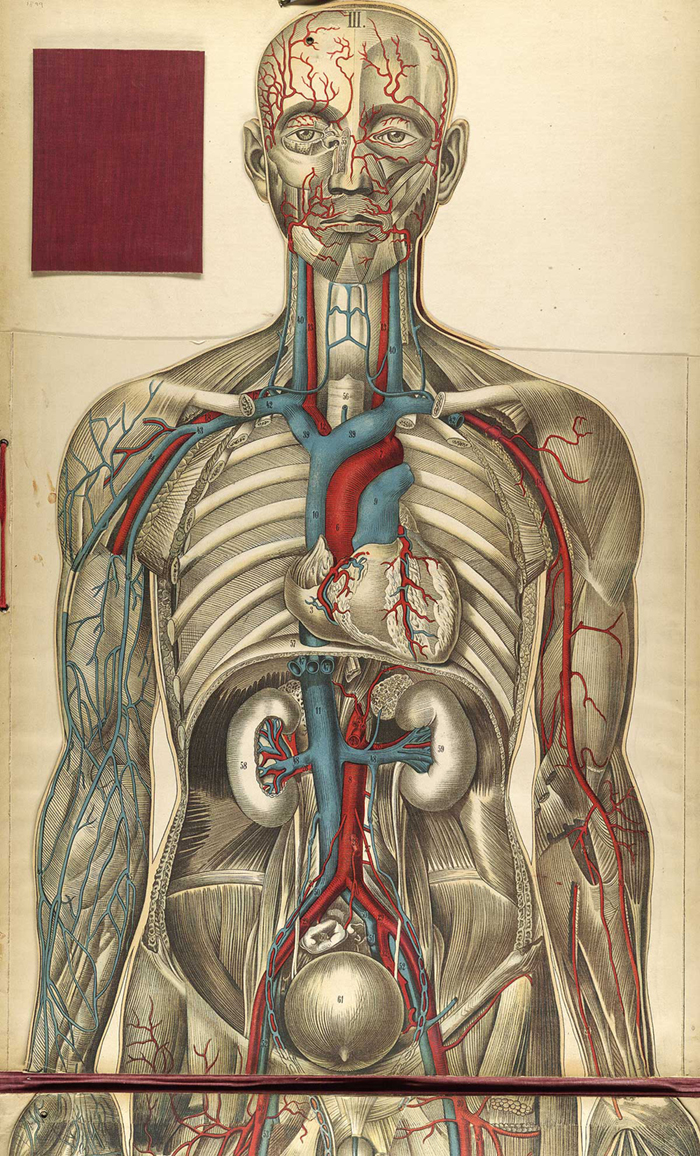

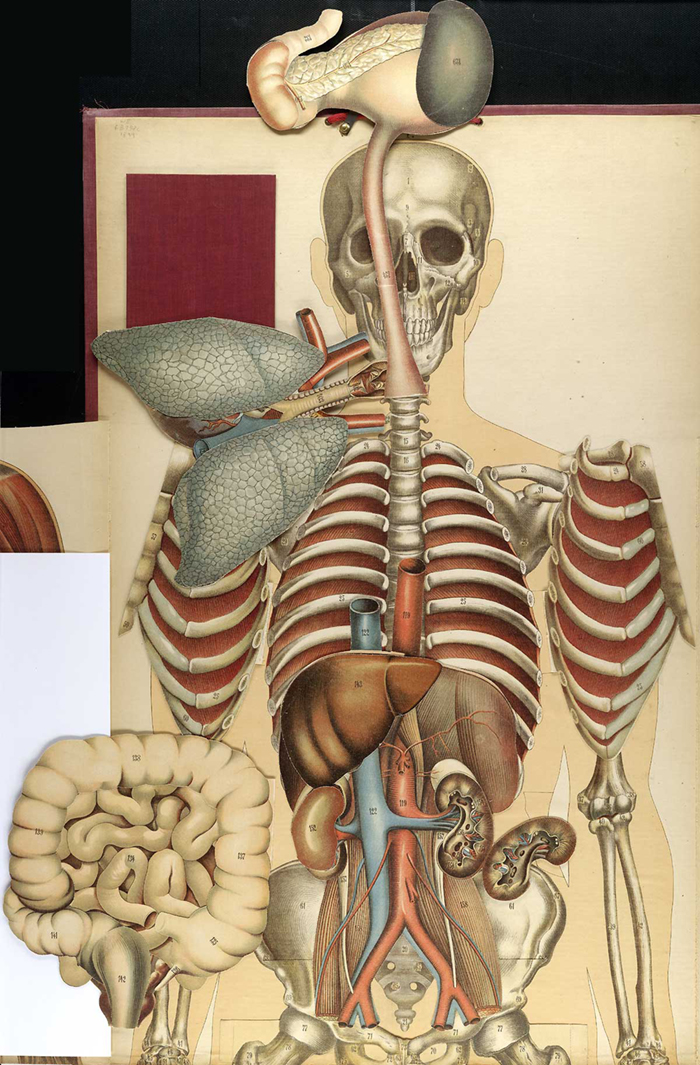

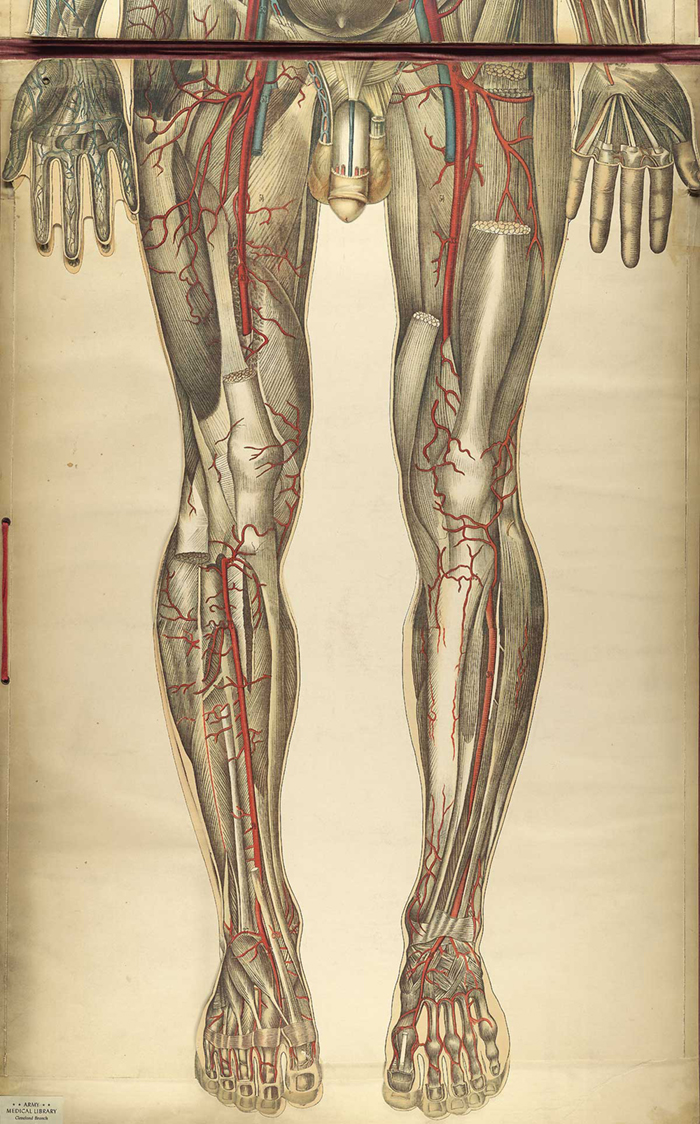

Julien Bouglé | Le Corps Humain et Grandeur Naturelle: planches coloriées et superposées, avec texte explicative | 1899

All digital images © U.S. National Library of Medicine