Henriette Cauvin, née Baral, died January 20, 1882, aged 34

For many people, a cemetery is a morbid location, a reminder of the hopefully distant but unavoidable end to our earthly tenancy; it would be the last place to visit in search of enjoyment, especially during a summer holiday. I have never been one of those people. I won’t say I feel at home in cemeteries (let’s not tempt fate too flagrantly) but these highly atmospheric and deeply revealing sites of remembrance have always struck me as some of the most fascinating places to visit when traveling. All of human life is there, so to speak, and these labyrinthine cities of the departed can also offer a great deal of architectural pleasure.

A couple of weeks ago I was staying in an apartment by the port in Nice, in the south of France, and on the other side of the building, rising steeply next to the street, there was a hill covered with trees. I had no idea until I climbed it soon after arrival that the city’s main cemetery was situated at the top, with views in all directions, out across the rooftops of Nice, to the Bay of Angels and the distant hills. The Cimetière du château, which is divided into Christian and Jewish sections housing 2,800 tombs, is an exceptionally lovely site. My sensation upon walking through the gate was closer to rapture at the prospect of exploring its avenues and ascending levels than to melancholy. There were many statues among the neo-classical tombs and chapels and I knew I would take plenty of pictures.

Cimetière du château in Nice, France

Cimetière du château in Nice, France

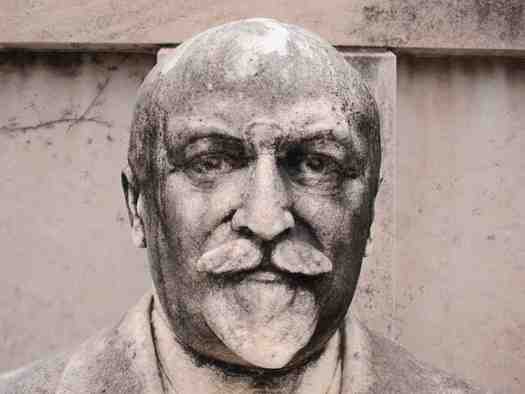

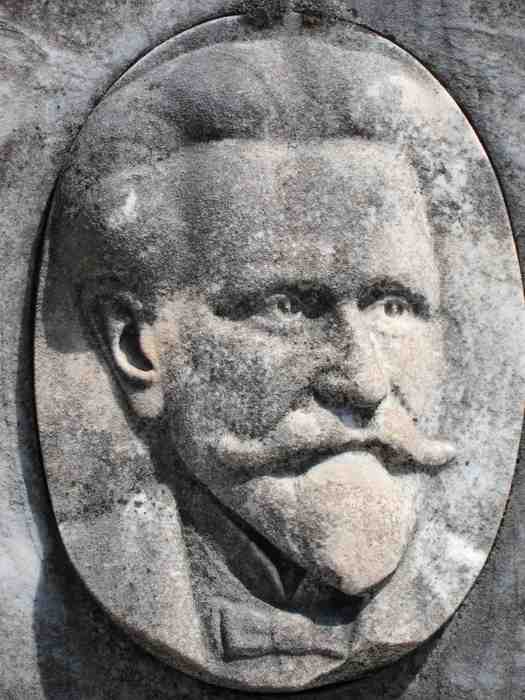

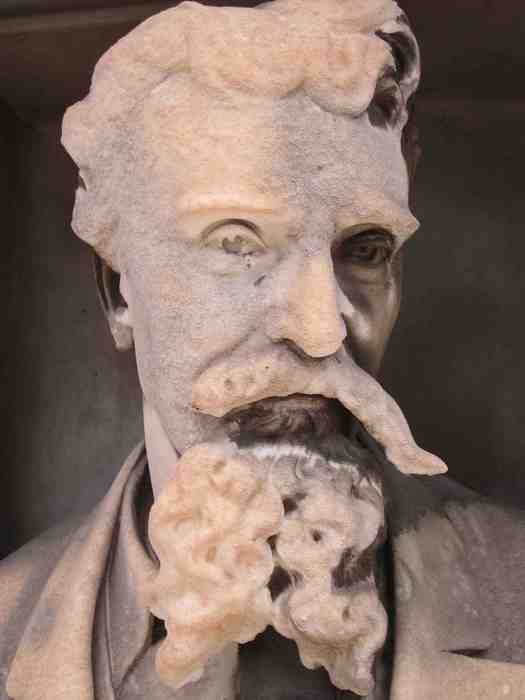

I hadn’t been wandering very long before it occurred to me that there were more portrait sculptures adorning the tombs than I have seen in many other cemeteries. With so much to look at, it’s easy to treat a cemetery visit as a series of general views without lingering to study what might prove to be more salient details. When you do pause to read a name, a date, or an epitaph, you are powerfully confronted with the reality of a person’s life and the emotions of those they left behind, also now dead in many cases. The funerary portraits, some executed in the round, some in relief, actualize the dead with a frequently startling vividness. I decided to search for the sculptures and look at them closely. Although I continued to take other pictures during my visit, I would concentrate on recording these individualized images in stone.

Docteur Louis Lehouco, 1834-1928

Zenon Nowacki, died September 27, 1914

It’s common in some countries to place photographs of the deceased on the tomb and the cemetery in Nice has sporadic examples, though the practice appears never to have become a fashion. The desperation implicit in this over-literalness is always a little uncomfortable and incongruous for the disengaged viewer. Eventually, decades in the future, as the picture fades, no matter how fervently the bereaved sought to keep memory alive, the same thing will happen that always happens to a grave and even a grand tomb. It will cease to be visited and tended, inscriptions will slowly lose their definition in the air, lead letters will become detached and lost (there are many examples in Nice), headstones and crosses will lie broken, and metal frames will rust and corrode — a particularly poignant and final form of dilapidation. Some tombs in the Nice cemetery are marked “Concession à perpétuité” as though the vicissitudes of time could somehow be held at bay by a legal ruling.

Strangely, with the portrait sculptures, time has wrought some subtle enhancements. In mimicry of the lives they record, which ended 80, 100 or 130 years ago, these stone memorials have aged and in the process acquired a patina, character and presence that it’s hard to believe freshly carved, or newborn, stone could ever have possessed. You look into their eyes and they seem to look back at you with an age-old knowledge and gravitas across the void of time. They have gone (I’m afraid I believe there is no celestial drawing room: they really have gone) yet thanks to the sensitivity of these uncredited funerary sculptors — did they work from photographic portraits, paintings or death masks? — the person’s spirit, or at least some idealized representation of it, survives; if, that is, we restore the departed for a moment by stopping to look at them. How long does a sculpture, one of so many in a necropolis that plenty of those holidaying below in Nice will never visit, wait between the occasions when someone pauses, takes it in, feels its reality, speculates about this unknown personality, and gives a long-gone human a brief moment of afterlife?

Josephine Tomatis, née Navello (?), died June 6, 1930, aged 80

Louis Bonzano, died September 7, 1908

As I left the cemetery for the first time, I was beginning to think I would like to write about the sculptures, though I knew that I needed more pictures to make a good set. But I hadn’t noted down their names, for lack of pen and paper, and it was unthinkable to “resuscitate” these strangers without recording who they were. They were already slipping into obscurity again. I would need to go back, attempt to retrace my random steps and find them. Even when I had located them all, along with some new sculptures, which took two more visits, it was sometimes difficult to determine, with tombs bearing several family occupants, the sculpture’s identity. In one case, with some misgivings — despite my positive intentions I felt like a tomb raider — I had to lift a heavy stone cross to one side to reveal the damaged lead lettering it concealed. In another, I have indicated uncertainty in the caption with a question mark. Other information is incomplete.

Victor Sabatier, born May 19, 1823, died March 9, 1891

Georges Fighiera, born March 28, 1883, died November 28, 1912

I did some rudimentary searching for all of these people — and found nothing. Their families were citizens of substance, wealthy enough to afford these impressive memorials, but all of the occupants are forgotten now. Only one of the individuals I photographed, Victor Sabatier, a painter of local landscapes, who sports a magnificent though broken moustache and beard, is in any sense “famous.” I wish I could say I had heard of him before.

Louise Dalbera, born March, 14, 1861, died January 30, 1880

Raoul Cottalorda, 1895-1918, killed in the Somme, reburied in Nice, March 3, 1921

Photographs: Rick Poynor

See also:

On My Screen: Bill Morrison’s Decasia

Every Poem an Epitaph: The Protestant Cemetery in Rome

Comments [3]

great essay. All this remembers me the phantasmagoric Joy Division's 'Closer', designed by Saville. Cemetery in Geneva, not Nice.

Best from Argentina,

Lucas López

08.17.11

11:40

Here are some of my photos if you are interested:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/constanzapacher/sets/72157606208097840/

Best from Edmonton,

Constanza Pacher

08.25.11

11:03

Constanza, thanks for sharing your set of pictures, which I very much enjoyed. I particularly like Fighting Demons, You Shall Not Pass (both close in spirit to cemetery pictures I have taken myself, not shown here), and your untitled final picture with its intriguing conjunction of old statues and modern geometrical architectural details, which takes us back to the old/new mood of the Closer cover.

08.25.11

12:15