According to the Department of Labor Statistics, hair design is big business. According to my uneducated guess it is a billion-dollar industry, between wigs, toupees, and all manner of stylists, styling products, and styling photos shot to sell pomades, gels, shampoos, nets, and more. No wonder, according to literature and the bible too, many characters are defined by their hair.

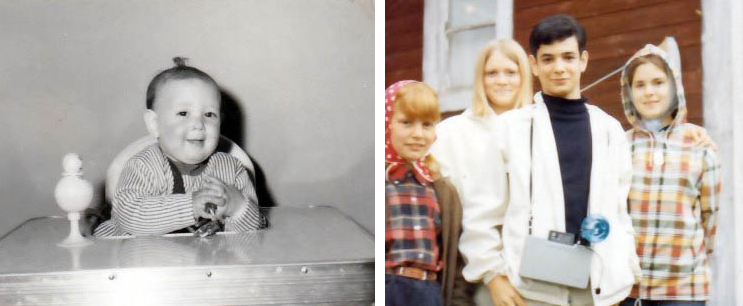

My hair, hair, hair, hair, hair, hair, hairYou could say that my life has been one bad hair day. From the get-go, my hair has been a divisive issue. As a five-month old baby, my mother insisted that I wear an adorable shock of hair on my noggin like a cockatiel’s crest. That presumably innocent touch of hair flair, perhaps an homage Our Gang Comedies’ Carl "Alfalfa" Switzer who wore a famously pomade-waxed cowlick (which he called “my personality”), sealed my fate as a hair-fixated neurotic. I had the mini-plume for a year, until Mom, who changed her own style and color every couple of months, decided it was no longer au courant, so she toyed with the idea of letting my hair grow into a Buster Brown cut. My dad, however, put his foot down and insisted Buster Brown was not the right persona for his son, and took me when I was about 2 ½ years old to get my first store-bought haircut.

Flow it, show it

Long as God can grow it

My hair

First haircuts are often traumatic . . . for mothers who routinely save their kid’s fallen locks for posterity along with the first bib, rattle, and bronzed baby shoes. Yet speaking of trauma, barber shops in Manhattan were rarely designed to accommodate the psychological consequences of small children under the scissor. These shops were as scary as a doctor’s office—but at least pediatricians used child psychology to trick their victims into acquiescence. For me, barbers were much more menacing! Mine could have passed for Edward Scissorhands but he was no Johnny Depp. Taped to his mirror were dozens of photos of his young clientele at the moment of the initial cut in various stages of hysterics (I made it to the wall of dishonor). That first cut, having being shorn like a lamb, resulted in a lot of tears. To stop my residual whimpering, I received a candy (and I’m still convinced barbers and dentists were in cahoots,for after a few haircuts the cavities emerged).

Hair design has always been important sign, symbol and mark of status. Growing up in the 50s and 60s hair suggested many things, including social class, cultural attitude, and aesthetic preference. From five to eight, more or less, I wore the all-American crew and butch cuts with the top glued upward. Crews were the favorite of jar-head athletes—and required little maintenance. But over the next couple of years, as I slowly freed myself from my parents’ grip, I began a coif rebellion. By nine or ten I went the greaser-route, like Elvis. I started with Vitalis, graduated to Brylcreem (“a little dab’l do ya”) and by eleven I had a full-fledged pompadour in the front with classic duck’s ass in the back held together by a green lacquer product known among the knowing as “elephant snot.” For JDs and wannabe delinquents who cultivated this look, the emerald goo (like glue) would harden the hair in place for a few hours, impervious to any natural elements. But when it melted, what a mess.

My mom hated the pompadour look. “You look unsavory,” she’d say. This was supported by the other mothers in Stuy Town, New York, where we lived, who wouldn’t allow their kids play with the local hood. When Elvis went into the army, the pompadour and DA (Duck’s ass) went south, so I tried a middle ground—not short, not long—with a part on the left and a slight bang in the front. Everyone seemed happy with my choice, even me. Until the Beatles.

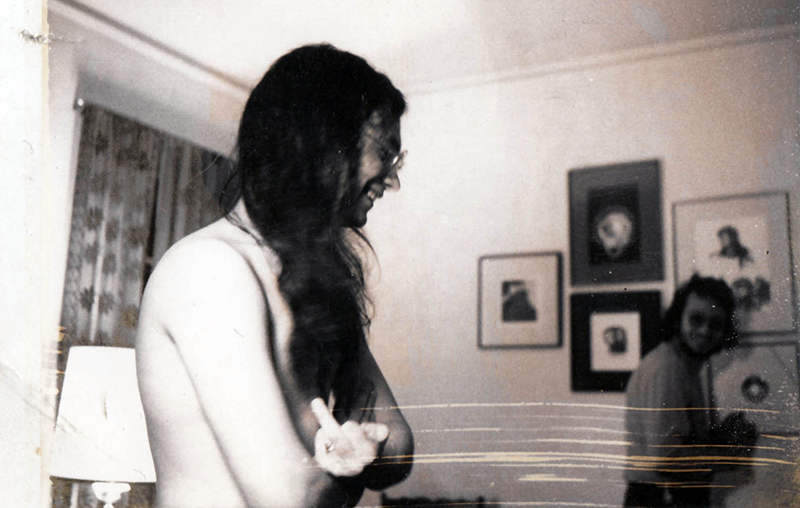

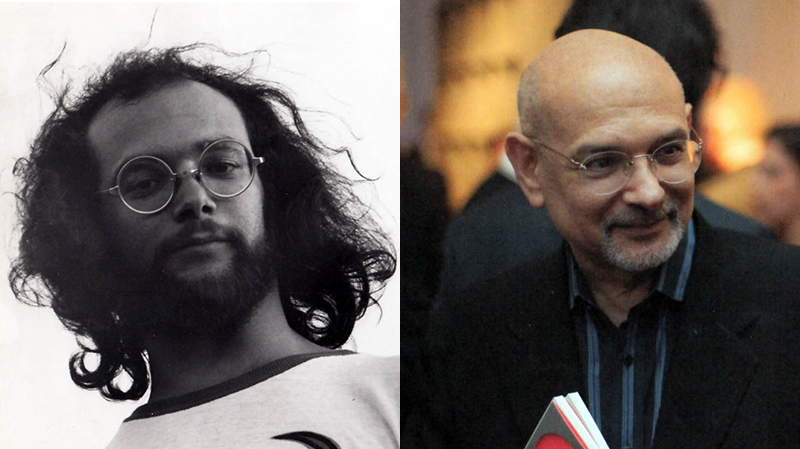

I recall when my mom nervously sneered, “I hope you never wear your hair like those . . . .” (I think she meant mop tops.) But that was all the excuse I needed to go Mod. In came the fringe and bangs (like Moe of the Three Stooges) and as their hair grew out, so did mine. The longer it got, the more frustrated and abusive my mom became. “I hope you go bald, like you father,” she harangued, insulting both me and my dad (who eventually got a hair transplant). Jeez, its only hair, I thought. But as the Sixties wore on, she’d berate my hair, as though it were an ugly wild animal I brought home. But me being me, I let it grow and grow and grow some more until it was all the way down my back.

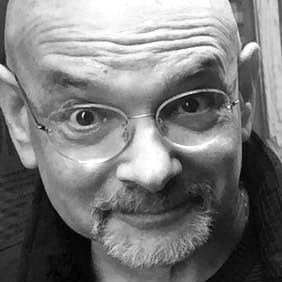

She wasn’t wrong. My excessively long hair was not the most pleasing of my various features. But it was my design, my signature, and as Alfalfa said, my personality. Paradoxically, mom won in the end. By age 20 her own dad’s genes showed up on my shower stall floor. By 26 it was clear that not even Hair Club For Men could save me. I was losing my personality at a rapid pace, forced to get regular haircuts or look like Benjamin Franklin. I don’t know what was more traumatic, the first haircut or the balding. Finally, at around 45, I had no choice but to shave it all off, secure only in the knowledge that people like Billy Joel and Michael Stipe were bald too. Shortly after it was all gone, I was visiting my parents, my mom said ruefully, “What a shame, you had such beautiful hair, would you like me to buy you a toupee?” Thanks mom!