“Vainglory,” an anachronistic term meaning an unjustified and excessive pride in one’s own achievements or abilities is one of the primary forces animating and shaping contemporary culture. The phenomena that is American Idol owes its considerable popularity both to its role in discovering legitimate, almost freakishly superhuman singing skill, but also as a window into contemporary culture’s vainglorious soul. From William Hung to Sanjaya Malakar, to the multitudes of nearly nameless aspiring Beyoncé imitators, American Idol draws a large measure of power from the vainglorious displays of the painfully talentless. A critical component of the show’s success resides in early rounds marked by limitless displays of stupefying arrogance by countless untrained, unskilled and unaware contestants. Like throwing Christians before lions, the deliciously evil pleasure of reveling in another’s misery may temporarily slake the thirst of the populace, but it’s also a horrifying look behind the veil at the monstrous face of Mediocrity itself.

Sid Vicious and Sanjaya Malakar

Vainglory is the symptom, mediocrity the disease.

Whereas historically, bravado has been the parasitic twin of bell curve-busting skill, American Idol provides a clear view of an historical value inversion. We now find ourselves living in a culture that has so thoroughly jettisoned any concern for craft (more accurately “Techné”) that the display of bravado comes before, and in spite of, the act of mastery. The issue is at best inconsequential if we’re concerned only with the condition of pop music in 2011. But we’re not. American Idol is an exceedingly easy target serving a rhetorical end, and as such it is a powerful display of our social mores.

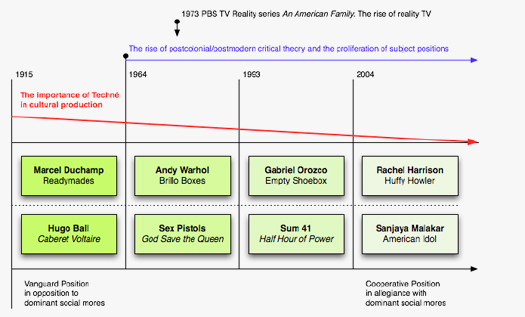

The conversation becomes exponentially more difficult, but no less horrifying, when we broaden the cultural terrain to include the role of Techné in (nearly) all aspects of culture today. By drawing a line from Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades (1915) to Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), then Gabriel Orozco’s Empty Shoebox (1993) to Rachel Harrisons’ Huffy Howler (2004), we find what began as a radical counter-cultural concern for the conceptual (in opposition to the technical) has shifted over time from a vanguard oppositional position, into farcical status quo. We also find the institutionalization of critique supplant the real thing — genuine opposition. We could find a similar tectonic shift at work by tracing a line from Hugo Ball and the Cabaret Voltaire to the Sex Pistols, through Sum 41 and on to Sanjaya Malakar.

Techné in Cultural Production, chart by Elliott Earls, 2011

Put simply, in 1915 Duchampʼs Readymades eschewed facility, craft, mimesis, and technique and were a radical palliative to stultified notions of technique, craft, skill and “art.” The further we track the arc of this argument back in time the more radical, relative to mass-culture, the work becomes. The important point here is that Duchampʼs Readymades, or Ballʼs work at the Cabaret Voltaire, suggest possibilities unassimilated by mass-culture. Well, things have changed. Orozcoʼs Empty Shoebox, Harrisonʼs Huffy Howler and countless other examples are merely masquerading as radical. They are indeed the kind of work that would elicit howls of protestation from red-meat middle American soccer dads; “You call that Art? My three-year old could do better!” Even though the ability to illicit scorn and derision from middle-America is often used as proof of artistic merit, these works are not radical. They are anti-radical.[1] Ironically despite the protestations of our fictional soccer dad, and unlike work by Duchamp or Warhol, these works perfectly reflect middle-American values. In fact Orozcoʼs early work and Harrisonʼs Huffy Howler, not unlike the legions of aspiring American Idol contestants, actually buttress the contemporary disdain for facility, skill, craft, technique and critique. Rather than representing oppositional cultural practices, these artists inhabit a cooperative position in allegiance with dominant social mores. The fact of the matter is that Skill is just simply too damn hard! [2]

The irony of this should not be lost. As we track the increasing momentum of postcolonial/postmodern thought and the proliferation of subject positions available to practicing artists, we are also tracking the increasing complicity of artists and designers in the dominant social program. Although it may seem that Iʼm focusing on the end result (the products and the forms), at the expense of a discussion of the underlying theoretical framework that enabled these positions, Iʼm actually attempting to point directly at them (the frameworks and the results). In that process, it’s my intent to raise difficult questions regarding artistic agency in contemporary culture.

Holland Cotter, in a review entitled “Slicing a Car Fusing Bicycles and Turning Ideas Into Art,” describes Orozcosʼ Empty Shoebox as “a single empty cardboard shoebox left on a gallery floor. This was a perfectly judged gesture: commanding in its modesty, vulnerable in its openness, and obliquely critical. Intended as a sly reference to the cramped exhibition quarters heʼd been allotted, the piece might also be read as a comment on the scant room given to Latin American artists in history.” [3]

The piece might be read this way; or, the piece could be read this way. But there is also the distinct possibility that this reading is an inversion and a justification. And even though both of these works may accurately reflect the “unmonumental” [4] impulse within contemporary art, that donʼt make it important. As a matter of fact, it may even render these works unimportant.

So what’s the problem?

The challenge of “Evaluation” is a particularly difficult issue in the cultural shitstorm of mediocrity that is 2011. Stable criteria for the evaluation of works of art, for good reason, are nearly impossible to establish. Thinking beyond the simple binary of good/bad, a far more productive way of trying to understand the value of this type of work deals with the issue of fecundity. Is the work fecund? Is the work in question fertile? Does the work establish a rich cultural terrain able to produce and to sustain numerous offspring? This is a wholly different question than is a work “good?” A work can be both “good” and “unimportant.” A work can also be both “bad” and “important.” [5] Duchampʼs Readymades, from the perspective of any number of traditional criteria, may in fact be bad, but there is simply no doubt that they were/are critically rich, deeply important work. In a word, fecund. However, the cultural context shifted before, during and after the creation of these specific works by Orozco and Harrison. These works are progeny not progenitor. The pendulum has swung and just like city-slicker artists, contemporary culture — with its emphasis on “user-generated content,” “crowd sourcing” and other anti-professionalist forms of cultural production — have little use for Techné. [6]

Rachel Harrisonʼs Huffy Howler (2004), and Gabriel Orozcoʼs Empty Shoebox (1993)

What’s at Stake?

The real issue here is far from a light conversation concerning the merits of either Sanjaya Malakar or Gabriel Orozco. Iʼm sure Malakar is a wonderful person, and itʼs clear he possesses enormous charisma. And both Orozco and Harrison are artists well worth discussing. The real issue is what the aforementioned work tells us about our cultural values from both a pop cultural and a critical cultural perspective. The real issue concerns the diminished role of Techné within nearly all aspects of contemporary humanities from Youtube to the Venice Biennale. The real issue is the suggestion that radical, truly critical, fecund and important work within the humanities might necessarily lead back to a genuine concern for Techné. The real issue is the disturbing complicity with the larger cultural program of Mediocrity displayed by “artists” of every stripe. Whatʼs at stake is not a simplistic call for a return to “craft.” This too leads us nowhere. In the full measure of its meaning, Techné is a means to an end, not an end in itself.

Larry Gagosian, and Lockheed Chaise Lounge (1986 ) by designer Marc Newson

I need a hero... Now for the suckerpunch.

In an article discussing the “design-art” market in relation to both designer Marc Newson and king-pin Larry Gagosian, Alice Rawsthorn suggests that “Throughout the 20th century, artists abandoned expressions of beauty to explore political and social concerns. Many delegated the production of their work to concentrate on its conception, like designers. Design changed too. Technology enabled designers to usurp the artistic role of creating beauty — it's hard to beat an iPod for sheer lusciousness — and to exercise greater control over production. The end result is a purer expression of their vision.” Rawsthorn goes on to state “Art and design are increasingly intertwined. Artists like Thomas Demand, Liam Gillick, Jorge Pardo and Andrea Zittel explore the material culture of design.” [7]

In the end is this a simplistic call for a return to design process, methodology and history? Should Marc Newson be our hero? Is his 1986 Lockheed Chaise Lounge, which sold at auction for $968,000, the obsessive virtuosic exemplar of Techné in contemporary design/art that this essay so desperately needs for its cathartic ending? Is Marc Newsonʼs design practice, and his products, a constructive model poised to rectify society's ills? Far from it. I wish it were only that simple. Undoubtedly Marc Newson makes beautiful, compelling and well-crafted work. However, in a Platonic conception of Techné, itʼs clear that the goal of a craft is is not craft itself. [8]

Thus, the real issue is the disturbing complicity with the larger cultural program of vainglorious Mediocrity displayed by “artists” of every stripe. Clearly this implicates designers as well, but possibly from the other side of the coin. [9] Consider the problem of “evaluation” again for a moment. As in all forms of art, “fecundity” should be the issue. The potential, difficulty and richness of these questions are far more important than any answers they pose.

Make/Do is the theme of DesignInquiry 2011 on Vinalhaven Island, Maine.

Notes

1. Deborah Sontag addresses the context for Orozco's early work: "At that point, after the crash of the 1980s art-market boom, Ms. Temkin said, there was 'a real disgust with art that looked expensive and monumental.' This created a particular receptivity for, as Mr. Orozco put it, 'a young rebel from abroad' who, reacting against what he called the 1980sʼ decadence, was experimenting with understatement." While it is important to acknowledge this context, this may simply underscore the idea that this work inhabits a cooperative position in alignment with dominate social mores. Deborah Sontag, “A Whale of a Return to MoMA.” The New York Times, December 11, 2009.

2. Deborah Sontag adds: “In a similar spirit the MoMA show followed, and then an exhibition at Ms. Goodmanʼs gallery in which Mr. Orozco, in Yogurt Caps, pinned four transparent Dannon yogurt lids to the walls of a bare room.” Deborah Sontag, “A Whale of a Return to MoMA.” The New York Times, December 11, 2009.

3. “Dodging commitments to mediums or styles, he took improvisation as his baseline method, and turned personal quirks into assets. Studios made him antsy, so he did without one. Instead he wandered, poked around, made art from what he found, often where he found it. Sometimes he created, added to or tweaked a situation. He photographed the results: a mist of warm breath on a dark wood surface; a pattern of circles traced by wet bicycle wheels; oranges, like little celestial bodies, placed, one per table, on a receding line of tables in a outdoor market.” Holland Cotter, “Slicing a Car Fusing Bicycles and Turning Ideas Into Art.” The New York Times, December 13, 2009.

4. Unmonumental was a 2008 exhibition at the New Museum “about fragmented forms, torn pictures and clashing sounds. Investigating the nature of collage in contemporary art practices... Unmonumental also describes the present as an age of crumbling symbols and broken icons.” The exhibition featured work that had “a distinct informality: conversational, provisional, at times even corroded and corrupted,” work that was ”un-heroic and manifestly unmonumental.”

5. Arguably the Sex Pistols are “bad,” but very important. Inarguably Sanjaya Malakar is “bad” and very unimportant.

6. “Goethe would argue “’The artist who is not also a craftsman is no good; but, alas, most of our artists are nothing else.ʼ Earls would argue that, ‘alas, most of our artists are neither craftsmen nor artists.’” — Joshua Ray Stephens.

7. Alice Rawsthorn, “The Designer Newson Teams Up with Gagosian Gallery - Style & Design.” The New York Times, January 21, 2007.

8. Plato. Ion (535-538).

9. Extrapolating on this idea, isnʼt the necessary implication that Orozco, Harrison and Newson are “Mediocre?” No, Orozco, Harrison and Newson are worthy of close scrutiny precisely for what their work tells us about our culture. The fundamental premise of critique is that all work can be called into crisis. The Techné of criticism involves finding fault lines within all work in an attempt to build a kind of feedback loop between Episteme (the domain of “knowledge”) and Techné (the concern of “craft”) in order to make better work. So if a primary criterion of an artworkʼs merit is fecundity, (and the author feels) that this essay raises difficult issues that are engendered by the work of these three artists, does that mean ipso facto that the artworks in question are fecund?

1. Deborah Sontag addresses the context for Orozco's early work: "At that point, after the crash of the 1980s art-market boom, Ms. Temkin said, there was 'a real disgust with art that looked expensive and monumental.' This created a particular receptivity for, as Mr. Orozco put it, 'a young rebel from abroad' who, reacting against what he called the 1980sʼ decadence, was experimenting with understatement." While it is important to acknowledge this context, this may simply underscore the idea that this work inhabits a cooperative position in alignment with dominate social mores. Deborah Sontag, “A Whale of a Return to MoMA.” The New York Times, December 11, 2009.

2. Deborah Sontag adds: “In a similar spirit the MoMA show followed, and then an exhibition at Ms. Goodmanʼs gallery in which Mr. Orozco, in Yogurt Caps, pinned four transparent Dannon yogurt lids to the walls of a bare room.” Deborah Sontag, “A Whale of a Return to MoMA.” The New York Times, December 11, 2009.

3. “Dodging commitments to mediums or styles, he took improvisation as his baseline method, and turned personal quirks into assets. Studios made him antsy, so he did without one. Instead he wandered, poked around, made art from what he found, often where he found it. Sometimes he created, added to or tweaked a situation. He photographed the results: a mist of warm breath on a dark wood surface; a pattern of circles traced by wet bicycle wheels; oranges, like little celestial bodies, placed, one per table, on a receding line of tables in a outdoor market.” Holland Cotter, “Slicing a Car Fusing Bicycles and Turning Ideas Into Art.” The New York Times, December 13, 2009.

4. Unmonumental was a 2008 exhibition at the New Museum “about fragmented forms, torn pictures and clashing sounds. Investigating the nature of collage in contemporary art practices... Unmonumental also describes the present as an age of crumbling symbols and broken icons.” The exhibition featured work that had “a distinct informality: conversational, provisional, at times even corroded and corrupted,” work that was ”un-heroic and manifestly unmonumental.”

5. Arguably the Sex Pistols are “bad,” but very important. Inarguably Sanjaya Malakar is “bad” and very unimportant.

6. “Goethe would argue “’The artist who is not also a craftsman is no good; but, alas, most of our artists are nothing else.ʼ Earls would argue that, ‘alas, most of our artists are neither craftsmen nor artists.’” — Joshua Ray Stephens.

7. Alice Rawsthorn, “The Designer Newson Teams Up with Gagosian Gallery - Style & Design.” The New York Times, January 21, 2007.

8. Plato. Ion (535-538).

9. Extrapolating on this idea, isnʼt the necessary implication that Orozco, Harrison and Newson are “Mediocre?” No, Orozco, Harrison and Newson are worthy of close scrutiny precisely for what their work tells us about our culture. The fundamental premise of critique is that all work can be called into crisis. The Techné of criticism involves finding fault lines within all work in an attempt to build a kind of feedback loop between Episteme (the domain of “knowledge”) and Techné (the concern of “craft”) in order to make better work. So if a primary criterion of an artworkʼs merit is fecundity, (and the author feels) that this essay raises difficult issues that are engendered by the work of these three artists, does that mean ipso facto that the artworks in question are fecund?

Comments [22]

06.16.11

12:12

06.16.11

01:58

Things have changed since Duchamp's readymades, most importantly, the default value of an art object is no longer craft and beauty. Donald Judd suggested that it's interest value. There's a wide variety of art production happening that runs the gamut from craft and beauty to work that's more akin to Rachel Harrison. Actually a stroll through Chelsea will indicate that indeed craft and beauty STILL dominate the art world. It's also not radical to compare these contemporary artists to Duchamp, why? Because the game is different. What is radical in 2011? Amazing craft? If that's the case, then Jeff Koons is the best artist.

One reason Orozco and Harrison stand out is because they ARE important. Their work addresses contemporary values brought on by the information age. To take their work out of context and and compare it to Sanjaya and Sum 41 is funny, but inaccurate.

You seem to call out all of these discrepancies yourself in the essay but you never get around to pinning down what it is your saying about craft. That it's not valued? Well I disagree, and American Idol might be the best example of America worshipping ONLY craft. Which means what? Bourgeois ideals are still riding high! Everyone wants a new, shiny, well-crafted car, a hard-body (well-crafted) wife, and an enormous well-crafted flatscreen to watch gifted singers belt out time-honored jams. Just because the art world is a tiny microcosm with a certain faction that doesn't have these ideals is no reason to shout that the sky is falling. I think it's safe to say craft and beauty still rule.

06.16.11

03:30

06.17.11

01:55

Since, everybody is blessed with a lot of qualities, no one can deny anybody of such chances. One should be proud of his/her talent.

06.17.11

02:07

But watch out for dry scientific minds who will take this kind of argument and use it the wrong way - think Denis Dutton: modernist art is degenerate because it doesn't respect the 'artistic instincts' of homo sapiens... There's a TED talk video about this theory which of course completely focuses on 'presentation' instead of content ;)

06.17.11

04:02

It is as Ponyboy asks: "What is radical in 2011?" and is that even the point anymore? Floundering radicalism/vanguardism is a sign of the times? Well yeah, ok. Earls is delineating the structure in broad strokes. My problem is this. It seems to me that Earls's position is preconditioned by radicalism being a viable practice, inasmuch as it is the purpose. Every endgame I can think of that is techne-centric leads to one where "originality" takes primacy. And it isn't that "its too damn hard" but that such an endgame is unsustainable and at the turn of the century, fervently vanguarding into the wilds has become such a solipsistic exercise that the most of it becomes irrelevant anyway. We talk of "important" work, but that happens in tandem with the village, not in the woods. For instance, take the greyhat hacker group Lulzsec. Personal affiliations and values aside, they exist both inside and outside of the system and are made powerful for it. While complicity to social mores may be indicative of a cultural retreat from radicality, it also necessitates the need for real, true, meaningful radicalism that extends beyond form or insular frameworks; beyond design and art and into that exact blobby mess that happens to be the home of the disease Earls mentions.

If pointed Duchampian strategies were once radical and have waned to indifference, then Lulzsecian attitudes are the endgame. To misquote Lulzsec, "Keep your money, we do it for the lulz." And in the structure that Ponyboy suggests is still prevalent, this move is a natural transition/backlash (regression?); and perhaps the radicalism to answer his question (and a weird Joker to Earls's Batman).

*http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/praxis/museum-of-non-visible-art-praxis-and-james-franco?ref=video

06.17.11

10:53

All of the lasting thrills that I receive from Good Design have been due to designers radically altering our interactions with our physical manifestations in such a way that it is immediately clear that future works are just waiting to pour from the edifice they've created, and that the work, while rigorously and fully realized, is the start of something even better.

Experiencing that thrill is why I design. The idea that just maybe, someday, I could give it to someone else has never ceased to be romantic for me, even as almost everything else has.

06.17.11

02:54

06.18.11

03:36

You missed the period on your last sentence. Oh and you should capitalize Cranbrook.

Cheers.

06.19.11

08:14

06.20.11

06:59

I am particularly grateful that as an educator at a leading institution, you are engaged in the present.

06.21.11

11:57

I posted a link to the article on Facebook. Now only if I could Like it.

06.22.11

09:14

06.23.11

09:38

design your own shoes

06.24.11

04:04

06.26.11

06:02

06.26.11

11:46

Urban Outfitters-esque spoon-fed customization has removed techne from the picture and makes it ever the more difficult for a designer to legitimize their existence. It's a double-edged sword. More people than ever appreciate design now or have design knowledge based on the media/reality tv/the products we buy. However, with this comes people DIYing the hell out of everything, not wanting actual designers in the picture anymore.

This may seem like whining, but actually I think this calls for more techne and understanding of the fundamentals in design to stand out. This doesn't mean more re-hashing of the German, Dutch and Swiss (which I think speaks to American Idol-covers of songs and a re-hashing of design aesthetics from the old masters both show a love of "things you have already seen and know aka same as it ever was but I digress...), but a stronger hold on design knowledge and less on trend following. Intellectual techne? The etsy-genre of graphic design just doesn't cut it.

While this may be a tired conversation in the art-world with Un-monumental feeling so long ago already, it is something that I think is definitely worthy of a conversation on DO.

06.27.11

02:20

07.07.11

11:54

07.08.11

03:31

07.13.11

10:04

07.14.11

06:02