Hair, hair, hair, hair, hair, hair, hair

Flow it, show it

Long as God can grow it

My hair

—James Rado, Gerome Ragn, Hair, the musical.

Shining, gleaming, streaming, flaxen, waxen, hair has been the subject of myth, lore, and legend. Sampson derived his great strength from his locks, but when the seductive Delilah had a servant shave his hair, Samson loses his strength and is captured by the Philistines who blind him by gouging out his eyes. Extreme? Perhaps. Not as biblical, but no less impactful, a shaved head was historically a sign of disgrace. A punishment dating back to the dark ages up throughout the twentieth century, forcibly removing hair remains common retribution for moral outrage.

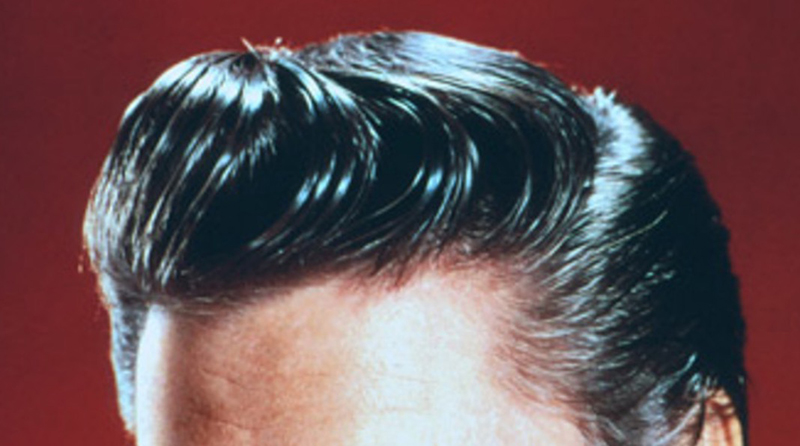

Donald J. Trump has teased the current hair obsession more than anyone since The Beatles. Although few emulate Trump’s preternatural coif in the way that youth culture copied Elvis’s pompadour and sideburns, or The Fab Four’s shaggy mop-tops, the President’s emblematic comb-over has earned considerable attention for its chromatic luminescence and tectonically engineered majesty.

Graphically speaking what is the first thing that identifies a person? Eyes? Nose? Ears? Teeth? These are all distinctive characteristics that, unless altered by natural and unnatural causes, are primary identifiers of most human beings. Arguably, how one wears their hair is the most important sign of personal identity. A hairstyle is more than just style; it is a trademark or, if you will, a logo for a personal brand. Hair is a graphic device, every bit as designed and ultimately mnemonic as any other vivid iconography.

Fashion often determines hair styles, but often hair styling defines the fashion of a time or place. Despite inevitable anomalies, hair is a signpost: long white wigs were the rage in the late seventeenth century among aristocrats, short powdered wigs in the eighteenth, the neo-classical Titus cut emerged in the nineteenth century and intricate and simple styles come and go returning to the past and signaling the future.

Hair defines personal brand identity. But Trump is certainly not alone in the employ of hair-as-statement. The military haircut has long been an essential part of a uniform that underscores conformity. The military Mohawk is one such iconic do. Said to have originated with people of the Mohawk nation, it was actually popularized as a style in 1939 in the Hollywood movie Drums Along The Mohawk, returned as a punk style in the 1970s, and periodically since has raised it cockish crown.

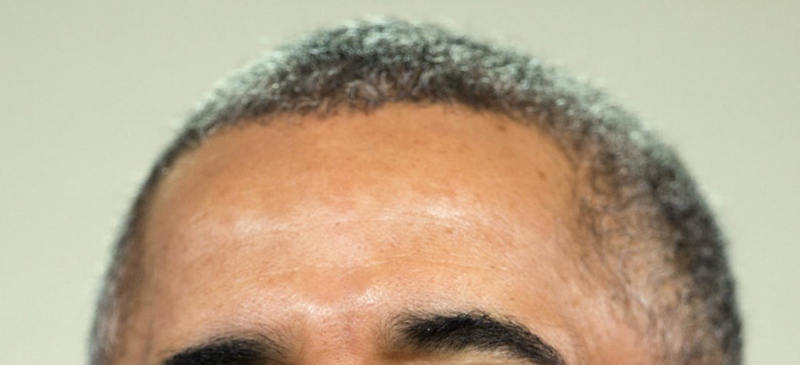

There are indeed many kinds of body decoration used for religious, spiritual, ideological, and social representations but hair (or the lack thereof) heads the list of personal identity traits that constitute the brand personality of the wearer—whether as an individual or member of a group. Just look at the hair-branding in the photos here. These recognizable styles are not just arbitrary cuts, but deliberately designed identifiers. In Mythologies (1957) Roland Barthes writes about the “Roman Fringe” hairdo in the 1953 film Julius Ceasar directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, where all the main characters wear the fringe and asks: “What then is associated with these insistent fringes?” Believing that this hair style exudes self-righteousness, virtue and conquest he adds. We “see here the mainspring of the Spectacle—the sign—operating in the open. The frontal lock overwhelms one with evidence, no one can doubt that he is in Ancient Rome.” The fringe is a “little flag” on the forehead—a sign of authenticity.

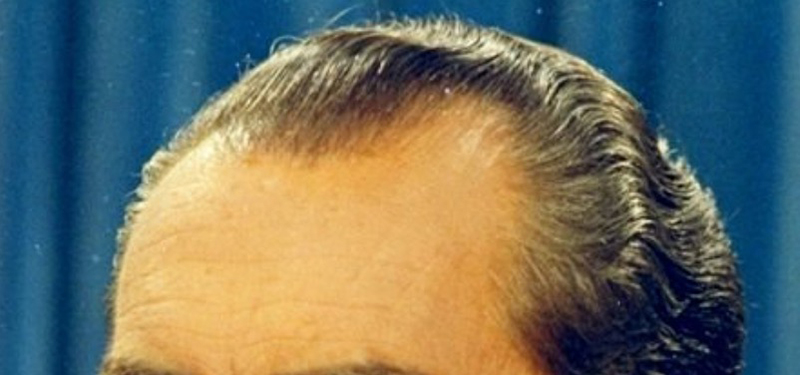

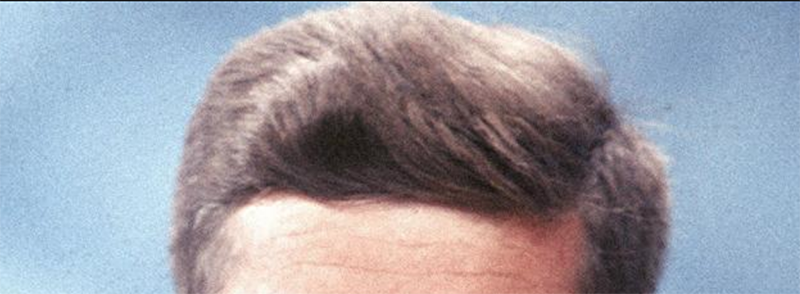

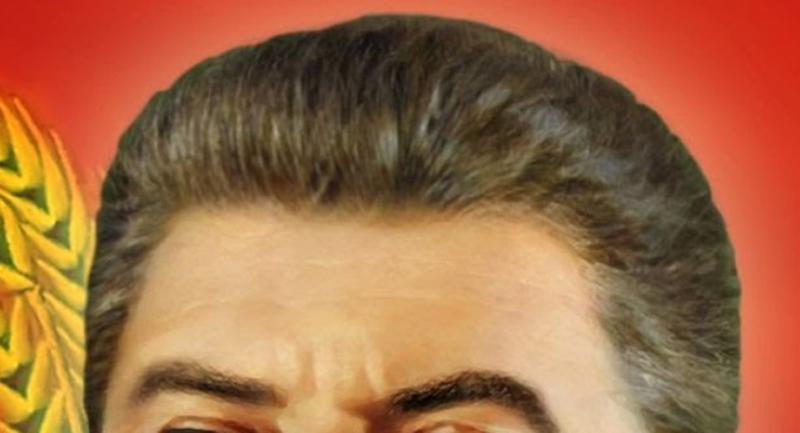

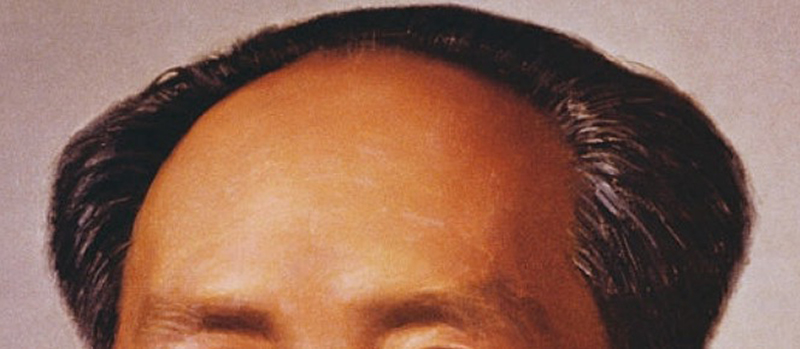

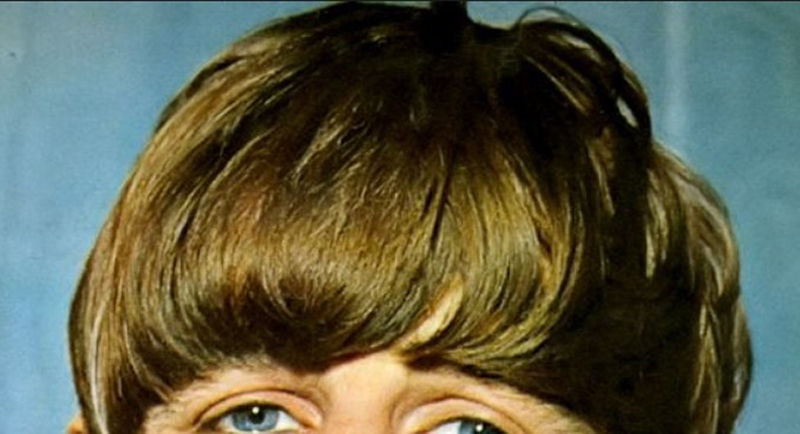

Similarly, the hair styles of those selected here are definitely symbols of either movements or moments in time, signs of belief, marks or badges of heirarchy. Hitler’s casually falling bang was designed to exude youthful rebellion against the old regime. Likewise, John F. Kennedy’s thick tufts of hair was new and refreshing during a period of transition. Theodore Roosevelt’s short crop spoke to his adventurism. Nixon’s greased back widow's peak told of his establishment values. Ringo’s bangs were a generational alternative to Elvis’s good-ole-boy power-pomp.

Hair is more than a fibrous protein. Hair is who we are, or at least what we project we are. For some, even biblically the Nazirites (Numbers 6:9-12), hair symbolizes everything. No wonder some of us miss it when it's gone.

Hairlines top to bottom: Donald J. Trump, Elvis Presley, Barak Obama, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, Kim Jong Un, John F. Kennedy, Joseph Stalin, Chariman Mao, Ringo Starr, Theodore Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler