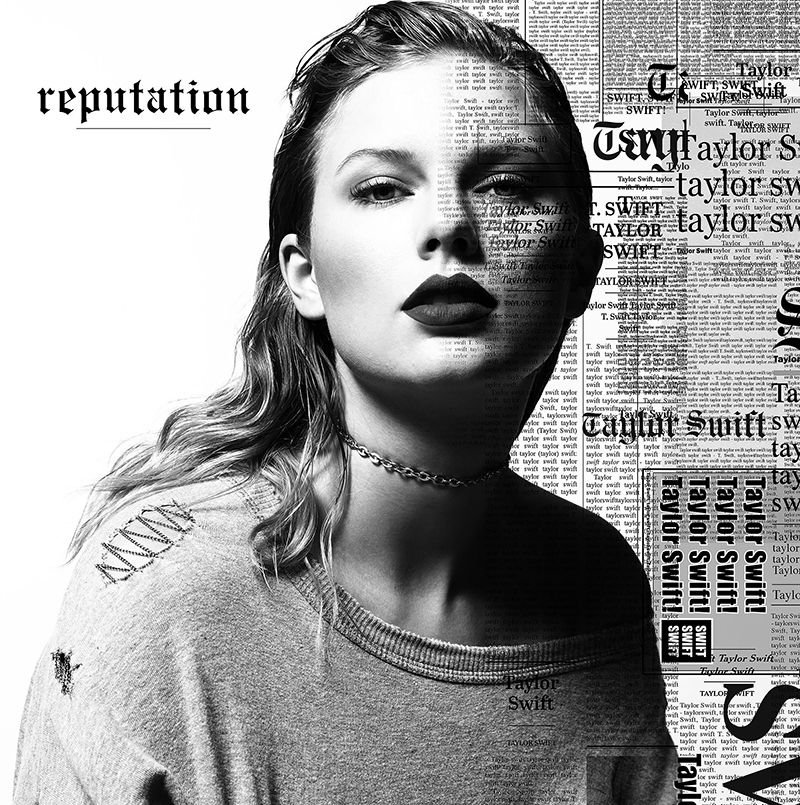

So our collective attention is now drawn to Taylor Swift’s upcoming album, Reputation. The album cover art and first single have just been released and scores of armchair critics are now poring over every detail in a kind of Talmudic exegesis.

The album cover’s color scheme is black and white. She is captured in a high-contrast photograph. Such an image creates a highly graphic effect and removes most of the mid-tone shadow from her face. This is very much in line with how she has been portrayed in the past. Most photographs of Taylor Swift have been lit and retouched so as to remove all planes from her face. She is idealized and unsullied. A flat plane punctuated by perfect lips. With almost imperceptible lower eyelids.

The detail in the image is in her hair and clothing. Her face is framed by an artful composition of hair which may be greasy, but probably isn’t. She’s too clean for that. The sweatshirt collar is stretched out and there is a studied bit of patchwork on the shoulder. Some on the internet interpret this all as a symbol of struggle, but the overall effect is too calculated. It shows a mild struggle, with mild exposure and mild danger.

Unlike most young adults, Taylor Swift has been able to take the bumps of a young person learning about relationships and convert them into her work. These are both her music and her celebrity. There are reports of her steely determination when in public: never letting her guard down, and able to handle even the weirdest situations which fame might bring. Recently, she showed uncommon bravery in court when presenting her groping trial testimony. Another situation includes Kanye West interrupting her acceptance speech at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards.

Both parties have made the most of this moment. Whenever either one has an album or appearance to promote, they stoke the flames with some sort of apology, song, or video—all basically promotional stunts.

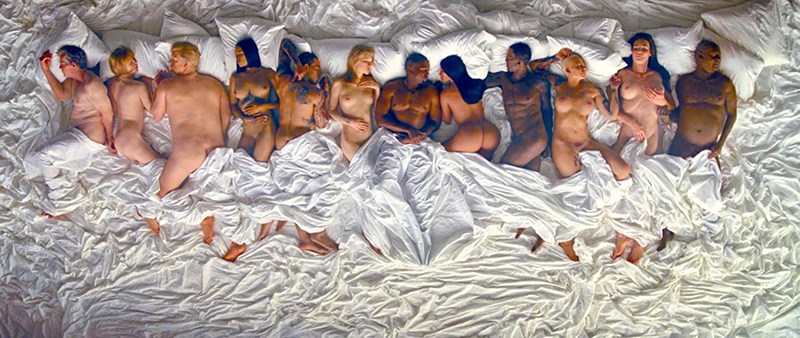

Seven and a half years later, the video for West’s “Famous” portrayed a series of celebrity wax figures nude, in bed around him. Swift’s figure is to his right—the position of John the Baptist in religious painting—and Kim Kardashian’s figure is to his left—Virgin Mary. The sheet draped across the figures is arranged like the loincloths covering the crucified Christ in Netherlandish Renaissance painting. The lyrics? "I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex/Why? I made that bitch famous/Goddamn, I made that bitch famous.”

Cut to veiled award acceptance speeches, leaked backstage rants, leaked recordings of telephone calls—honestly, who really gives a damn—and now the upcoming Reputation, scheduled for release on the 10th anniversary of the death of West’s mother.

As West stole the images of various celebrities and the visual language of art for “Famous,” Swift steals herself in Reputation. The title is set in a fraktur typeface, otherwise known as German Blackletter, Old English Gothic, or a variation of that sort. This is both a style of letter that appears on the New York Times masthead and in the rap music world, from album covers to thug life tattoos.

The right half of the design is a screen of multiple simulated newspaper layouts where the only words are “Taylor” and “Swift.” She is the sole content. Just her name, and nothing else. All comments and detail to be found in the music.

The text screen covers the shadowed side of Swift's face. Having spent many years myself as an album cover designer, I don’t read too much into this. One of the more frequent requests I’ve had from musicians is to be photographed coming around a corner, or from behind a screen, as if they are presenting themselves. Swift may have her own interpretation for the move, but I see it for the graphic trope it probably is.

Ultimately, this light controversy between Swift and West is an updated version of the Roxanne Wars, which itself is part of an old tradition known as the answer song. Taylor Swift may aspire to high art, but this is most definitely a step towards the middle. In the March 1978 issue of Rolling Stone, the respected critic Greil Marcus described the Clash and their own sense of embattlement: “The wars the Clash are turning into music—wars of class, race, and identity—are all too real…but the war the Clash are actually fighting is, for better or worse, mostly a rock ’n’ roll war; a struggle to define and seize the essence of the music, to take over its history, to refashion its past and future.”

Swift, and her animus, West, are still in a battle of power and romance. Each steals a bit of thunder from the other. Our eyebrows are raised in mild shock. And the spectacle goes on.