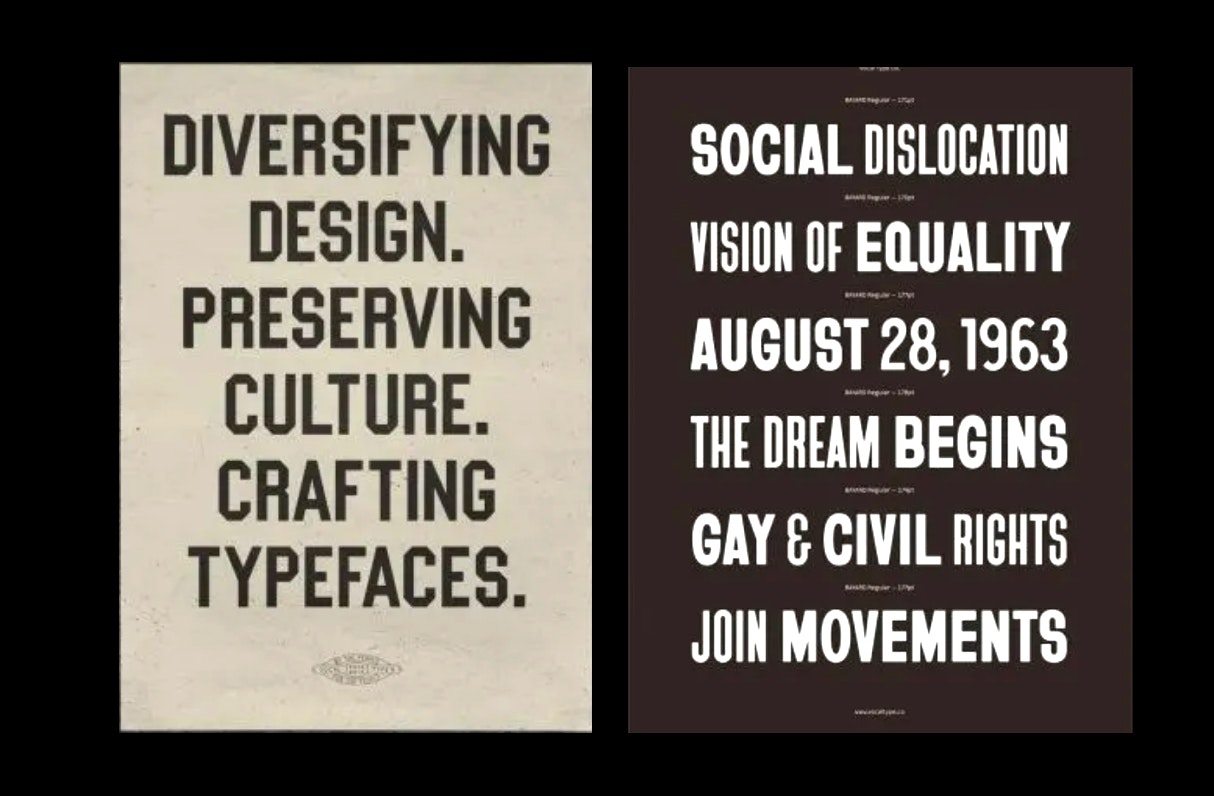

Vocal Type : a series of typefaces based on protest signs from the 1960s. (Tré Seals.)

The World Health Organization defines civil society as the space for collective action around shared interests.

We are a society. And it’s time to get civil.

The word itself is loaded. (Why can’t you just be civil?) Yet it needn’t be: civility suggests politeness (which is nice, if not always actionable). But the root of the word comes from the Latin word civilis, meaning relating to public life, befitting a citizen.

In a society, those citizens help each other. Or at least they should. This it what it means to be of service—to someone else, for the good of something bigger than yourself.

This, it seems to me, is at the core of what it means to teach. To educate is to be a steward—of an idea, of a community, of a succession of individuals who are, at turns, younger than you, in need of you, and way more vulnerable than you.

If education is the bedrock of a civil society, we’ve got some work to do.

Over the past week, I have read countless lists and letters outlining demands by students for change at their respective educational institutions: from Harvard to Yale, ArtCenter to RISD to MICA and OTIS, the tone ranges from imploring to accusatory, but the narrative is consistent.

These students want change, and they want it now.

To be fair, the faculty at these schools are listening, and their responses are neither defensive nor resistant. But change takes time, and with a global pandemic throwing economic volatility (including, and especially student debt) into even greater uncertainty, emotions are fraying.

That economic reality is not something I, or perhaps any of us can address here. I can no sooner reallocate endowment funds than I can influence hiring practices, but I can do one thing, and here it is.

I can be of service by rethinking the terms by which I do so.

For now, that means using Design Observer as a platform to access, aggregate, and amplify more expansive narratives and resources that can help all of us become better stewards of design. Terms of Service will become a new rubric on Design Observer where we publish our findings, share the mic, and open up a robust dialogue that is long overdue.

For now, some things to get us started.

To get a better sense of what it felt like to be part of a marginalized University community back in the equally turbulent late 1960s, take a look at some of the highlights from Brandon Holt’s 2015 thesis at Princeton. To look more closely at what it meant to be a Black designer in those years, the Letterform Archive’s seminal essay on the Black Experience in Graphic Design is a pretty good place to start. (Designer and education advocate Mo Woods wrote his graduate thesis about this same subject: you can read an excerpt here.)

And while we’re talking about the past, let’s look at the future: Words like future, when traced through 1,200 Black digital texts—spanning the years immediately following slavery to the peak of the Black Arts Movement—reveal a wholly different perspective on the Black experience, notes Rochelle Spencer, not just because such words were written by Black people over the last century and a half, but because they can illuminate the ways that Black people talked about how they saw their own futures.

Our futures are, now more than ever, a function of how we choose to live, together, in dialogue, with humility and understanding and grace. I may be a staunch advocate for self-reliance, but this is a collective endeavor that will benefit from what a community does best, and that is coming together to be of service to those who need us. They do.

And so do we. We welcome your submissions here.