Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the fourth chapter of Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth Century Art published by Princeton University Press and reprinted here by permission of the publisher. In this book, author Diana Seave Greenwald explores a history of art that uses digital research and economic tools to reveal enduring inequities in the formation of the art historical canon. This chapter is titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?: Artistic Labor and Time-Constraint in Nineteenth-Century America.”

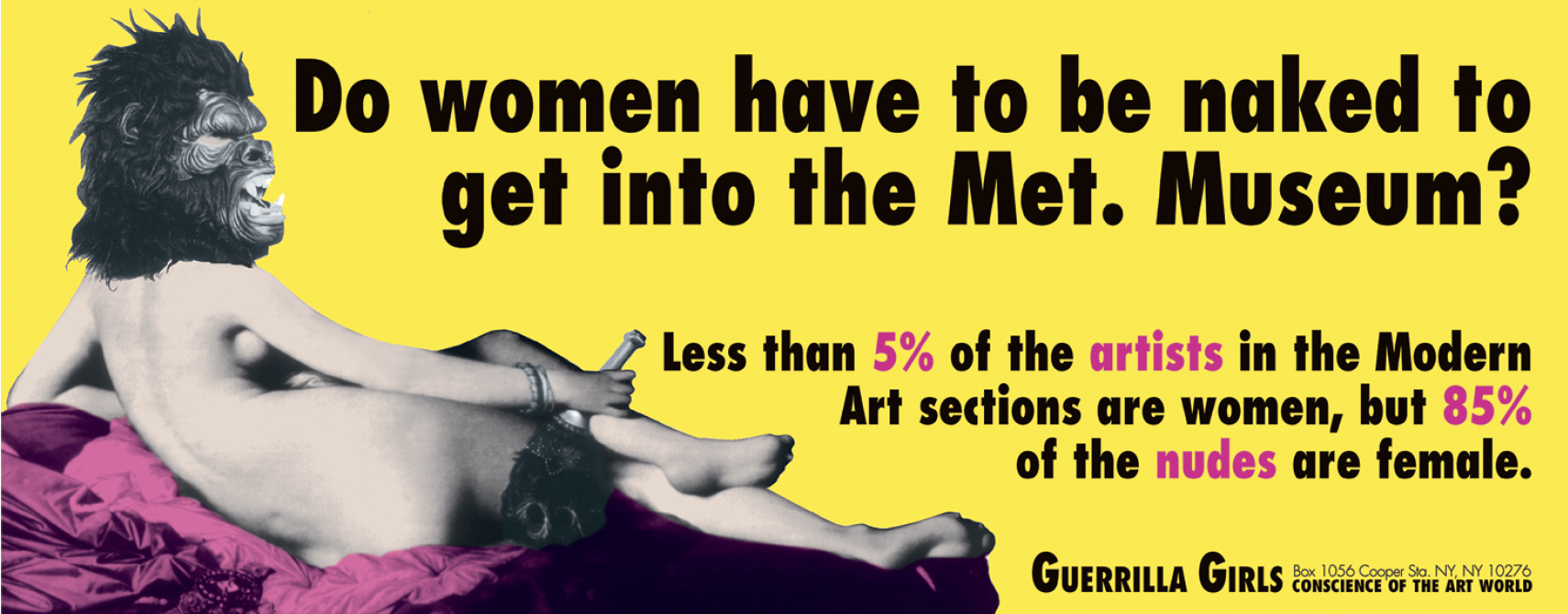

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the fourth chapter of Painting by Numbers: Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth Century Art published by Princeton University Press and reprinted here by permission of the publisher. In this book, author Diana Seave Greenwald explores a history of art that uses digital research and economic tools to reveal enduring inequities in the formation of the art historical canon. This chapter is titled “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?: Artistic Labor and Time-Constraint in Nineteenth-Century America.”The Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous feminist artist collective founded in 1985, call attention to systematic gender and race discrimination in the art world by cre- ating posters and handbills that feature a mix of dark humor, politics, and statistics.

One of their best-known posters features a send-up of French artist Jean- Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Odalisque (1814). In it, the Guerrilla Girls, who had collected data on the representation of women in major museum collections, posed a clear question: Do women have to be naked to get into the Metropolitan Museum of Art? The answer appeared to be “yes”—the collective concluded that 5 percent of artists in the Met’s Modern Art section were women, while 85 percent of the nudes on display were of women.

Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum? 1989 Copyright © Guerrilla Girls, courtesy guerrillagirls.com.

This 5 percent figure provokes myriad questions. Do fewer women than men make art professionally? If so, has this been true both historically and at present? In economic terms, this could be explained by supply and demand. If there is a lack of supply, what are the practical barriers that block women from making art? Or is this underrepresentation explained by a lack of demand for the works women produce? Does discrimination by collectors, gallerists, and curators stop women from getting their fair share of wall space in major museums?

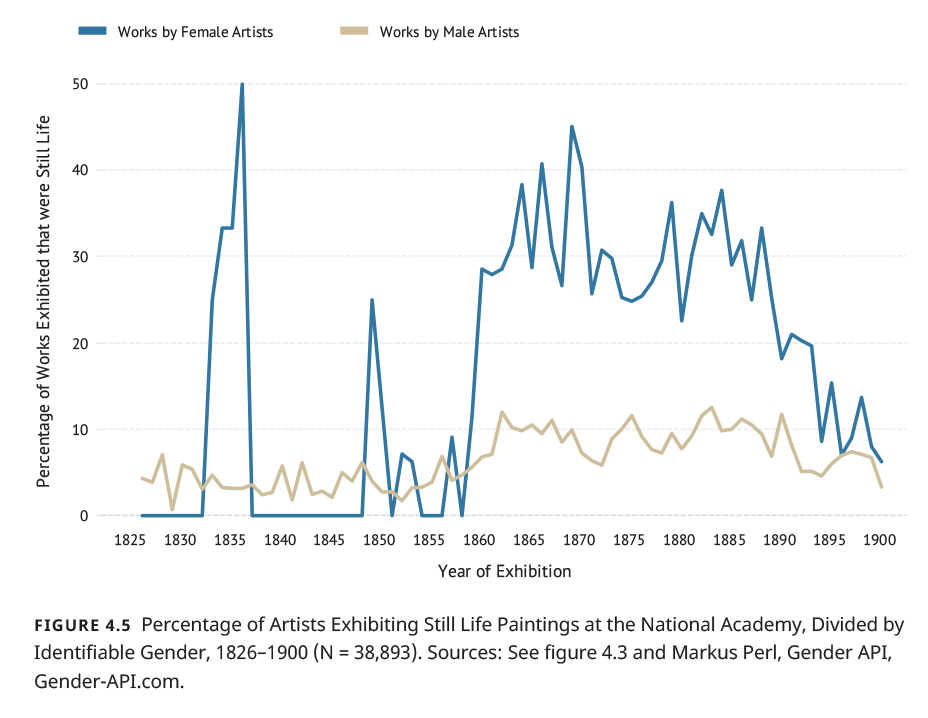

Note that the percentage does not equal 100. Only a fraction of makers of still life paintings were able to be identified as either men or women artists. The remainder of the makers either exhibited anonymously or with only using an initial for their first name. In these cases, no gender could be assigned with confidence. However, it is likely that a significant portion of these makers were women.

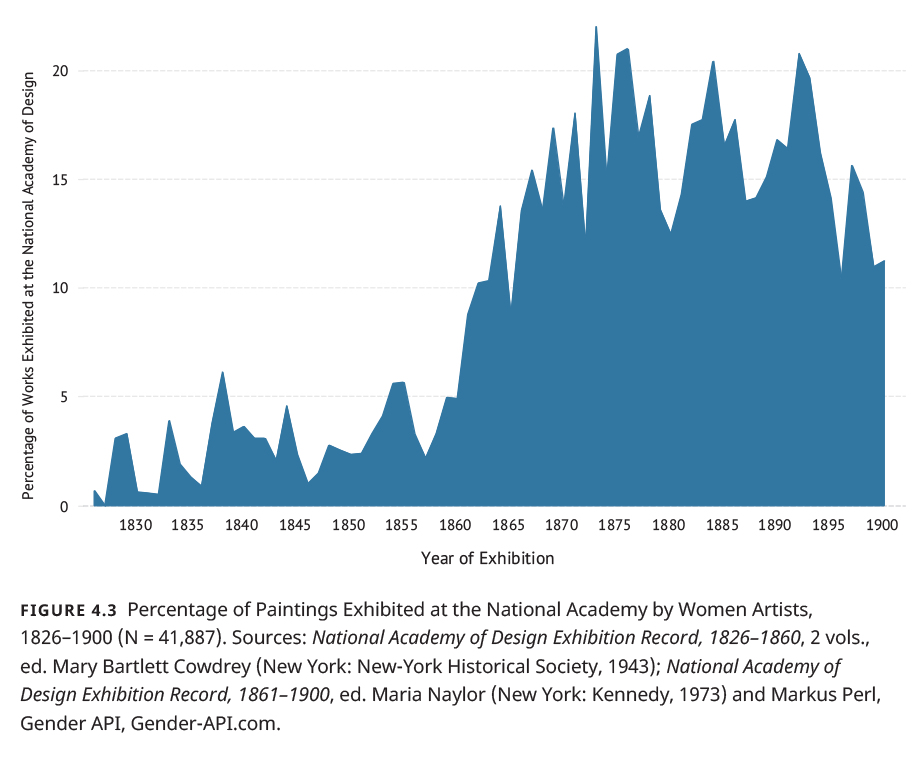

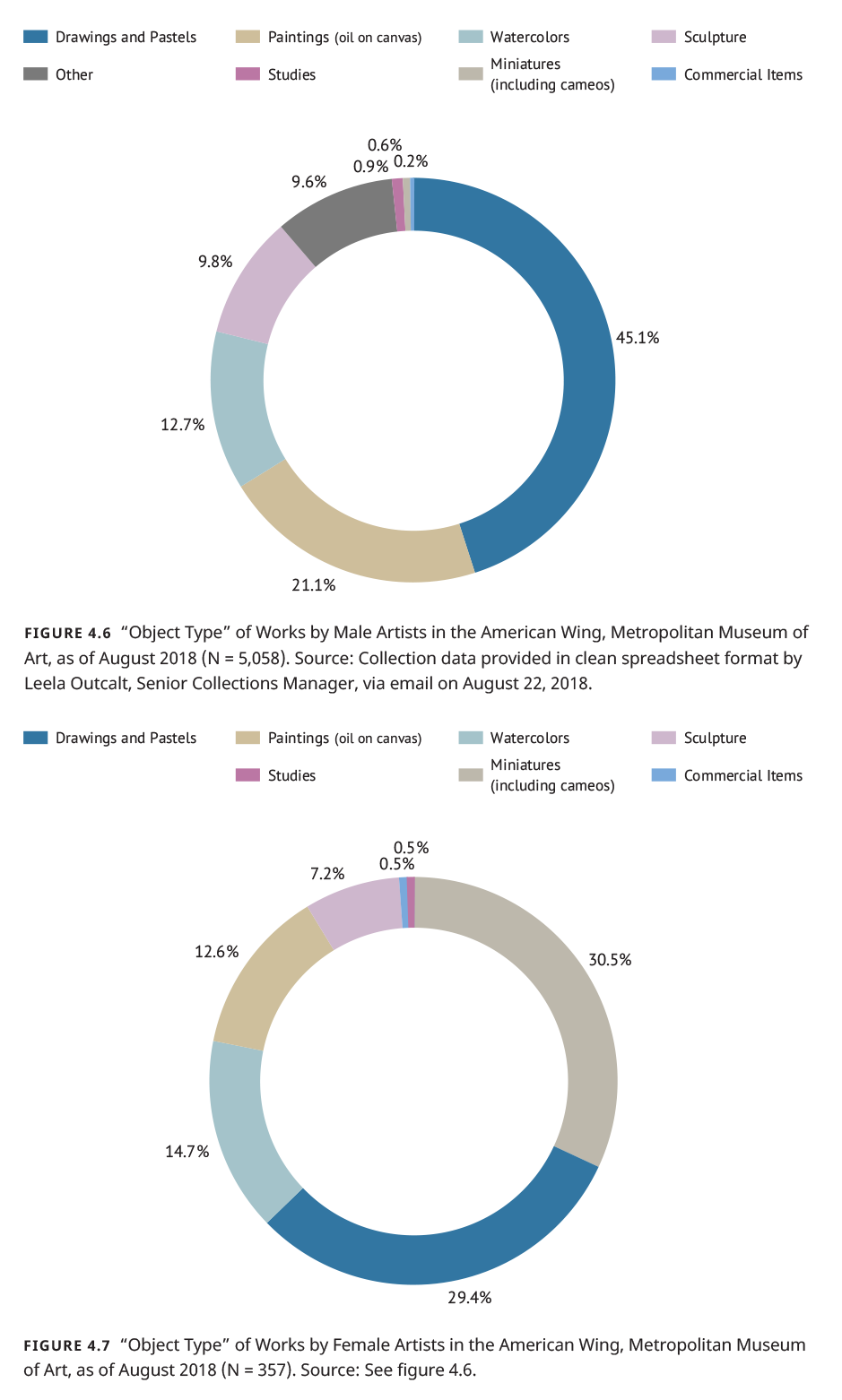

This chapter uses statistics to examine the experiences of women in the art world. Central to this examination is exhibition data from one of the principal art academies in the nineteenth-century United States—the National Academy of Design—and collections data from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the nation’s leading museum since the nineteenth century. Pairing data about the participation of women in important nineteenth-century Academy exhibitions with statistics about what has been preserved in an important museum makes it possible to con- sider the extent to which there is either a correlation or a disconnect between the amount of artwork created by women in the nineteenth century and how much of this output makes it into museum collections.

Analyses of these data reveal that women participated in nineteenth-century American exhibitions at much higher rates than they are represented in museum collections of nineteenth-century American art. The current scholarly literature treats this disconnect as the product of sexist cultural and institutional norms during the nineteenth century. Recent commentary has also focused on curatorial choices that have kept women out of museums’ permanent collections and exhibitions. Without denying the effects of both historic and current sexism, this chapter proposes other structural factors that limited nineteenth-century women artists’ attainment in their own lifetimes and posthumously.