The John Deere mural by Alexander Girard photo by: Ezra Stoller/ESTO

If the first John Deere were to walk in at this moment, I believe

he would recognize this building as his own. The honest directness

and the imagination that inspired him to throw aside tradition and

use what in his day was an extreme material — (imagine using

steel for a plow!) — is echoed throughout this building, inside and

outside, from top to bottom — even in the material from which it

has been built.[1]

Henry Dreyfuss

At the June 1964 opening of the Deere & Co. Administrative Center, the new headquarters (in Moline, Illinois) of America’s premier manufacturer of farm equipment, industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss offered a dual tribute to its architect, the late Eero Saarinen and to the company’s founder. Outside the auditorium where Dreyfuss spoke, a Cor-Ten steel pavilion displayed the “New Generation of Power,” the line of six-cylinder tractors his firm designed while Saarinen developed the architecture of the building. Inside Saarinen’s structure (Deere’s present) and alongside Dreyfuss’s machines (Deere’s future), was a representation of Deere’s past: the 3-by-8-by-180-foot long multi-media timeline of biographical, industrial and agricultural artifacts accumulated and arranged by artist, designer and collector Alexander Girard. Outside, visible through the sticks of steel, were grassy hills and a pair of ponds sculpted by landscape architects Sasaki, Walker & Associates — an idealized prairie for those machines to clear and cultivate.[2] Company chairman William A. Hewitt created an environment that spurred the architects and designers — all leaders in their fields and experts in corporate-image making — to specifically midwestern, homespun technical and representational innovation.[3] Deere’s engineers inspired Dreyfuss, who suggested Saarinen, whose building — laden with firsts, like the architectural use of mirror glass and Cor-Ten steel — sliced Sasaki’s rugged Illinois landscape as cleanly as John Deere’s revolutionary plow. While the three men’s work was all contemporary, it referenced the rural origins of the site and the company. It was Girard, in creating the mural permanently installed in the building’s display pavilion, who made the link between modern design and the folk past explicit by creating a structure and narrative for the outmoded, traditional and archival objects of Midwestern expansion.

Girard’s first role in the headquarters design was as an outside aesthetic auditor. After Saarinen’s death in 1961, Hewitt was nervous about leaving the unfinished interior design to Saarinen’s successors (the architectural design was mostly complete). He asked Girard to sit in on the architects’ meetings during the spring and summer of 1963. Girard was a personal friend of both Dreyfuss and Saarinen and had worked with Saarinen on the J. Irwin Miller house in Columbus in the mid-1950s.[4] He was also linked in numerous ways to the larger corporate design world, through work for Herman Miller, the Museum of Modern Art and Time Inc. Hewitt charged him with being an advocate for color and nature, feeling that Saarinen associates Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo and Warren Platner were too enamored of the machine-made. Minutes of these gatherings contain all the minutiae of interior design — the shelf for the president’s private shower, the tray for the secretaries’ rubber bands, the specification of black Heath tile and the development of new upholstery material for the office chairs by Girard. Hewitt later credited Girard for bringing more natural materials into the building — the leather tops for the tables and desks on the executive floor, the use of wood rather than metal for the executive office furniture, the silk curtains in the auditorium and last but not least, the framed Girard textile designs on each mid-floor stair landing.[5]

The Hallmark mural by Alexander Girard. Photo by Kristi Ernsting

The Hallmark mural by Alexander Girard. Photo by Kristi Ernsting

Simultaneously, Girard and Hewitt were discussing a “three dimensional mural,” along the lines of a 20-foot-long by 3-foot-high installation Girard had done for Hallmark in 1962. That mural, installed in the Hallmark corporate apartment in Kansas City, MO also designed by Girard, displayed gold cherubs, painted Easter eggs, candlesticks, vintage Valentines and a variety of hearts, held away from the gold-papered back of a long glass case on thin rods.[6] This piece, which now hangs outside the offices of Hallmark’s president and CEO, was intended to showcase the company’s material history in a modern, unsentimental manner — exactly Girard’s task at Deere, albeit with far less delicate material. The Halls of Hallmark were major supporters of modern architecture and design in the 1960s, and sponsored a number of early exhibitions of Girard’s nativities (including one at Kansas City’s Nelson Gallery of Art — now the Nelson-Atkins Museum — in 1962). In the design of the apartment and mural, Girard tried to move the company away from lace and chubby cheeks and toward the cruder and more direct representations of love, Christmas and family he collected. In apartment and mural he placed both kind of artifacts in cool, geometric settings that played up their color and graphic silhouettes. The apartment also included an indoor pool, geometric Moroccan rugs, and antique English dining chairs, indicating the breadth of design objects Girard’s architecture could assimilate. Hewitt must have been aware of this work in Kansas City, and sought a similar mixture of the handmade and the stylish for his own office interiors.

Girard was officially commissioned to do the Deere mural in June 1963, a year before the building opened. Hewitt was obviously excited: “In addition to it being visually beautiful, I believe it will provide an excellent means for tying a number of suggestions of the history of our Company to the new building in which we will work.”[7] Hewitt suggested that Girard rent a warehouse space in Santa Fe near his home and said Deere would start sending him material. John Kouwenhoven detailed the process in an essay in a pamphlet about the mural published to accompany its unveiling:

Even private offices of the Company’s executives were strippedof fondly treasured items. I remember the good-natured resignationwith which one factory manager parted with an old photograph thatthe Director of public relations spotted on his wall when we stoppedin to talk with him one day in December 1963.[8]

The mural files in the Deere archives list, in full detail, the masses of material it eventually transported to New Mexico. Girard established categories and the items were shipped in themed sets. Category 6, “John Deere the Man,” includes Deere’s 1830 hammer, made by the man himself in his Vermont blacksmith’s shop. Category 11, “Models and Toys,” includes several prototypes from the 1940s by designer Theo Brown. Category 15, “Souvenirs,” includes Deere-bedecked merchandise that ranges from clothes brushes to watch fobs to cuff links to tape measures, all with leaping deer, plows or the founder’s face.[9] During the summer of 1963, Girard and his wife Susan crisscrossed the Midwest, buying, at farm auctions and junk shops, the detritus of 19th century farms. He selected not for rarity or pristine condition but for shape, color and texture, weaving the mural in his mind complete with repeating motifs and antiqued tones. One of the last items he and Susan bought was an old straw beehive, found in Ohio, and a corn-husking peg that would complement the apple peeler and the cherry pitter already part of the mural. While most of the objects in the mural are not folk art per se, the models, toys and souvenirs spoke, by the mid-20th century, of a disappearing rural and early industrial past and their crude forms and materials offered the same contrast to the slick surfaces of the new building as folk art did in other Girard interiors and installations. As early as 1949, in his own house in Grosse Pointe, MI, Girard had covered select walls with paintings, ancient sculptures and knickknacks.[10] As his passion for collecting grew in the 1950s, the objects became more exotic and more precious, albeit ever changing and being rearranged.[11]

Once he’d collected a surfeit of items for the Deere project, Girard set about arranging them. Almost as impressive as the final mural is his maquette. He tacked an eight-inch by 15-foot strip of white paper to his wall-length bulletin board (the dimensions of Saarinen’s wall at the scale of one inch to the foot) and began to pin small, shaded pieces of paper to it. Each shape was an abstract representation of a specific object he had in mind and he could pin and re-pin them like so many entomological specimens. John Deere items were color-coded red, historical ephemera coded black. In January 1964, he moved up a scale, to one-and-a-half inches to a foot and achieved a whole new level of detail, making miniature facsimiles of most of the items, lettering two-inch broadsides, copying tiny weather vanes. The final product differs from this maquette in some small ways, as Girard changed his mind a few times on site, but overall it is a miraculous and miniature re-creation, a model of a model, if you will, of Deere’s all-American past. This maquette is currently on display next to the real thing in the Deere pavilion; Hewitt and his executives realized the value of showing the process. To my mind, Girard’s process reveals his architectural thinking even when immersed in Americana. His eye had picked the best items from the Deere archives and the state fairs, his visual memory had filed them away, but when it came to creating his composition he did it in the abstract, moving squares and blobs of colored paper around on a graph, like the buildings on a corporate campus, or the furniture in a showroom. The reason the Deere mural is legible, is more than a cupboard full of stuff, is because of its rational underpinnings. Girard was hired by Hewitt to soften the project’s hard edges, but he did that by introducing the rusty, the hand-crafted, the old-fashioned into the grid, rather than breaking out of it. Eventually, that grid was itself assimilated into the theme, as Girard developed a patchwork backdrop of old barn planks, some with weathered paint; smaller items were collected on top of sections of crazy quilts, rag rugs and shawls.[12]

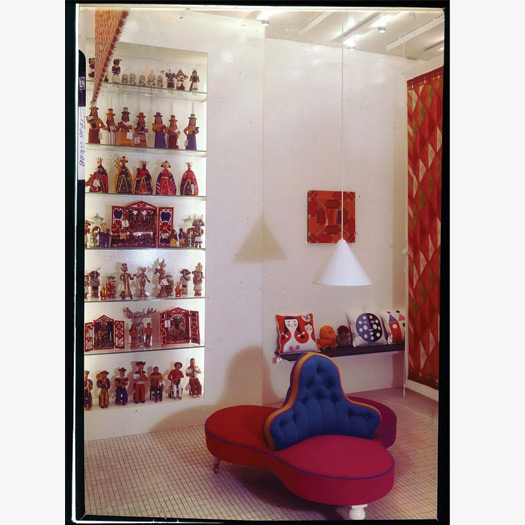

Textiles & Objects shop in Manhattan display Marilyn Neuhart’s embroidered dolls, photo by: Todd Webb, courtesy of maximodesign.com

Textiles & Objects shop in Manhattan designed by Alexander Girard, photo by: Todd Webb, courtesy of maximodesign.com

What is most impressive about Girard’s mural is its material reality. The objects do speak for themselves. An accompanying catalog was to identify certain items, or groups of items, and to put them in historical context, but only a pedant would really require this. There is a historical sweep from left to right, from 1837, the year Deere invented the steel plow, to 1918, the year Deere moved to mass tractor production. Top to bottom, one sees Deere in context, the mundane and the domestic, the historic and the farm, for each decade. The multiple themes and levels of objects float past one another on pegs that stick out from the wall, so that Girard can layer two-and three-dimensional items without hiding any part of an artifact. In her joint biography, Pat Kirkham credits Charles and Ray Eames with inventing the “history wall” as a means of contextualizing a historical subject with objects, but the Eameses’ first three-dimensional mural, A Computer Perspective, was installed at IBM’s Madison Avenue gallery space in 1971.[13] She notes that the couple was influenced by Girard, connected to them via their time in the Detroit suburbs and their designs for Herman Miller. The three also worked together on the 1955 exhibition Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India at the Museum of Modern Art. Girard designed the show, while the Eameses helped arrange the objects and created a short film of the result.[14] Later, Girard would help Ray Eames find appropriate items for the couple’s 1965 show on Jawaharlal Nehru. All three were expanding upon ideas about display getting off the wall, pioneered by Herbert Bayer at the Bauhaus and deployed by Bayer at a series of shows at the MoMA in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The most obvious parallel was Bayer’s use of a wider range of vision than had been typically seen in exhibition design: rather than a line of images at eye level, he deployed objects and artwork across the entire visual/vertical plane.[15] George Nelson’s 1953 book Display showed Bayer’s historical work, as well as a number of very similar systems of poles and scrims and shelves simultaneously developed by himself, the Knoll Planning Unit, Alvin Lustig, and others. He reserved special praise for Girard’s 1953 Good Design exhibit at MoMA:

This show is one with no backgrounds: all walls and the ceilinghave been painted black, so that they disappear; within the blackenvelope the exhibits appear, set on, against, into glowingsurfaces of light.[18]

It is clear from Nelson’s description that there is a close affinity between the technique Girard developed for his history murals of the 1960s and his exhibition and showroom designs of the 1950s and 1960s. The idea of floating an object — on a rod, on a glass shelf, on mirror, on a wire — recurs again and again, as do grids of those rods, shelves and wires, creating showcases within showcases, rooms within rooms. At the MoMA, he painted walls and ceilings black, covered the floor in parts with blackened cork and even used dark flock paper on some of the inner walls of the cases. For the 1961 Textiles & Objects shop in Manhattan, Girard went in the opposite direction, making the walls, floors, and ceiling of a long, narrow storefront white and layering within them chromed 3D grids, backlit translucent shelving, fabric-covered single-leg stools, and panels of his own Herman Miller fabrics (most with a latent grid of their own).[16] The lighting was designed to sparkle, tiny lights strung along the chrome uprights, so the stuffed and carved and painted objects within were both silhouetted and highlighted. Designer Marilyn Neuhart’s embroidered dolls stood, like a line of cubby schoolgirls, across a white-painted wire rack suspended from the ceiling across the front window.[17] The idea of the grid is a recurring trope in Girard’s work at multiple scales and in multiples fields. One sees it in the maquette behind the material at Deere, in the layers of shelves and racks at Textiles & Objects, and even, in his more folkish textile designs for Herman Miller (like “Fruit Tree,” or “Eden”) as an organizing principle for making a modern pictorial fabric.[18] When you focus on the space between the figures, you see the rigorous lines that separate one flower from the next. In translating his favorite handmade folk images and objects into an industrially manufactured fabric, Girard performed the same architectural and organizing action as he did in the glass cases at Deere or the galleries at MoMA. The broadness of Girard’s career has made it difficult to describe, as he went far beyond the traditional role of architect. But the combination of contemporary technique, material, and geometry with the color, crudity and animal nature of folk art, seen in these different contexts, creates a prominent common thread.

Detail of the John Deere mural by Alexander Girard by: Ezra Stoller/ESTO

In the Deere mural, those interested in technical history can follow a line of closely written patents across the wall; those interested in industrial design can look, instead, for the dull shine of steel parts, seats, harrows, rakes; there are fascinating old flower-shaped biscuit pans and flower-shaped hubcaps, teacups and fabric swatches. Reflected in the glass are the pavilion’s three-dimensional inhabitants — the tractors that all this history allowed the company to achieve. “What was good enough for his [John Deere’s] grandfather was no longer good enough for him,” Girard wrote.

A time when imagination and invention sprouted like new corn under a spring rain, exploding from the chrysalis for the old way into a new…To preserve fragments of this time—a collection of souvenirs — …A composite image that perhaps will evoke a mood — inspiring even though nostalgic — better communicated through the eyes than spoken or written.[19]

As a display Girard’s mural was highly sophisticated; as an exhibit it could not have been less pretentious. “Everyone seems to be able to identify with something in the mural, and then is fired up to study the whole thing,” Girard told Fortune. “There is nothing phony in the mural, and we are proud of this. The only synthetics are the plastic apples in the apple baskets.”[20] The opening ceremonies for the building, at which Dreyfuss spoke, were focused on a national and international audience. The mural, in contrast, was aimed at Deere’s local audience — dealers excited to bring clients to the new site, employees glad to have something to show their families, farmers who already identified with the company and who might see something of their own heritage on the wall. As an ensemble the Deere headquarters communicates the same way, through the eyes. Girard, Dreyfuss and Saarinen, though only occasionally working together, created an environment in which all the parts bear a family resemblance based not just on green and yellow, but on the distinct character — modern and folkish — of the Deere corporation. For Deere, Dreyfuss designed with ergonomics and metal stampings, Saarinen with mirror glass and Cor-Ten steel. Alexander Girard designed with folk art.

The Modern Design/Folk Arts opened October 15, 2010 at the State University, New Mexico and runs through December 17, 2010. More info here.

1. “Opening of the Deere & Company Administrative Center,” pamphlet, 1964. Deere & Co. Archives.

2. For more on Saarinen, see Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen and Donald Albrecht, eds. Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006 and Jayne Merkel, Eero Saarinen. New York: Phaidon, 2005. For Dreyfuss, Russell Flinchum. Henry Dreyfuss, Industrial Designer: The Man in the Brown Suit. New York: Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution; Rizzoli, 1997. For Sasaki, Peter Walker and Melanie Simo, Invisible Gardens: The Search for Modernism in the American Landscape, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994 and Louise A. Mozingo. “Campus, Estate and Park: Lawn Culture Comes to the Corporation,” in Everyday America: Cultural Landscape Studies after J.B. Jackson. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

3. William A. Hewitt, “The Genesis of a Great Building — and of an Unusual Friendship,” AIA Journal 66:8 (August 1977): 36-37, 56.

4. On the Miller House, see Christopher Monkhouse, “The Miller House: A Private Residence in the Public Realm,” in Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future.

5. William A. Hewitt, interviewed by Wesley R. Janz, April 23, 1992. Wesley R. Janz Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. These textiles are no longer extant. Employees used the stairwells as smoking areas, and for vertical circulation from the ground-level cafeteria, so the fabrics were damaged by smoke and spills.

6. “Greeting Cards Were Never Like This: Alexander Girard’s Apartment for Hallmark,” Interiors (November 1962): 100-105.

7. Hewitt to Alexander Girard, letter, June 6, 1963. Deere & Co. Archives.

8. John Kouwenhoven, Reflections of an Era (Moline, Ill: Deere & Co., 1964), 7.

9. Series 53374, Folder C80008. Deere & Co. Archives.

10. “Casual Vices for Girard’s House,” Interiors (January 1953): 76-77.

11. Sharon Lee Ryder. “A Life in the Process of Design,” Progressive Architecture 57:12 (December 1976): 60–67.<

12. “Rural Americana,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine, November 1, 1964. Copy, Deere & Co. Archives.

13. Pat Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, [1995] 1996), 266.

14. Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames, 279.

15. George Nelson, ed., Display (New York: Whitney Publications, [1953] 1956), 108-119; Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames, 268.

16. Nelson, Display, 142.

17. See “Display Case for Fabrics,” Industrial Design (July 1961): 66-67 and “Girard’s air conditioned bazaar,” Interiors (July 1961): 78-85.

18. Sarah Williams, “Meet the Neuharts,” The Scout, August 8, 2008: http://thescoutmag.com/features/design/37/meet_the_neuharts

19. Leslie A. Pina. Alexander Girard designs for Herman Miller. Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 1998.

20. Girard, quoted in Kouwenhoven, Reflections of an Era, 1. “Rural Mural for a Tractor Maker,” Fortune (December 1964): 144-147.

Comments [3]

10.19.10

09:22

Great post, I liked the Modern Design/Folk Art catalog so much I ordered twenty copies. I've been giving them out to various design scholar friends.

A chair from my collection is in this exhibition, and I helped Preston source a couple other items for the show. Now it's a pleasure to see that you are sharing your scholarship on line.

As time goes by, Alexander Girard's own designs look better and better, the designs are strong and the quality of the workmanship in his textiles without equal.

My compliments.

12.08.10

05:31

09.03.12

04:11