Honeywell Round thermostat, 1953; Nest thermostat, 2011

When my mother replaced her furnace eight years ago, she begged the HVAC guy to let her keep her old thermostat. After all, it wasn't just any thermostat: it was a vintage 1950s Honeywell Round, designed by Henry Dreyfuss, and likely installed when the house was built. If you grew up in an old house before the 1980s, the Round is a thermostat, in the same way the brown-marbleized box of Kleenex is tissues. Sad to say, the Round was incomptible with her contemporary heating system, and now she has a white textured-plastic box, with tiny buttons and a digital readout.

These plastic boxes, today's generic, were and are multiple steps backward. And someone finally noticed: former iPod hardware designer Tony Fadell, who created a new company to produce the Nest. A round thermostat, 60 years later and, at $250, unlikely to ever become the new Kleenex.

So ubiquitous was the Round, at least in my mind, that I found it strange that few of the critics who have covered the Nest mentioned it as a precursor. On the Atlantic Cities blog, Allison Arieff name-checks Dreyfuss's design as the last iconic thermostat. A long WIRED piece on Fadell misspells Dreyfuss's name and misdescribes the Round. Tech critics Farhad Manjoo and David Pogue, both in the New York Times, write as if Apple invented circles, and as if they've never seen a Honeywell. (This points to the vast and unnecessary divide between tech critics and design critics, but that's a discussion for another day.) Because it is not just the iconicity, or even the roundness that the Nest references, it is also Dreyfuss's insights about intuitive interactions, and Honeywell's marketing department's insights about the place of the thermostat in the home. A hat-tip to Dreyfuss isn't just common courtesy, it's revealing.

Honeywell Round thermostats ready for final checkout and packaging, Golden Valley (courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

A little history, courtesy Russell Flinchum's Dreyfuss monograph, Henry Dreyfuss, Industrial Designer: The Man in the Brown Suit. Dreyfuss loved to show off by drawing freehand circles, and frequently did so for clients on Oak Room cocktail napkins. As the story goes, Honeywell's president asked Dreyfuss for a radically new thermostat. Dreyfuss drew a circle and said, "Here. Go ahead and make something of it." It took the company more than 10 years to do so, given the internal complications of radical simplification. But there was continuous pressure from the sales department to make the round thermostat work, to differentiate Honeywell from its rivals, and to recognize the prominence of the thermostat in most homes.

Dreyfuss's round design couldn't be installed crooked, a common (and continuing) problem, and the front could be popped off and painted the same color as the living room. The original model even came with a base plate, to cover up the area where your previous thermostat had marred the wall. This was truly home technology, designed to grow and age and never be replaced. In a funny way, it is a tribute to Dreyfuss's good taste that the Round wasn't often painted, despite the option. The brushed gold he chose as the base color blends perfectly with most decor.

As Pogue writes, of the Nest:

Sweating over attractiveness makes sense; after all, this is an object you mount on your wall at eye level. A thermostat should be one of the most beautiful items on your wall, not the ugliest.Dreyfuss simplified the selection process, reducing heat control to its essence: one curved thermometer; two arrows, one for desired temperature, one for actual temperature; and one gesture, a hand to the Round's cupped surface, clockwise for hotter, counter-clockwise for cooler. In our Apple-y age, Dreyfuss's efforts seem a precursor for interaction design, which seeks to reduce an action to the simplest graphics and the fewest screen-based moves.

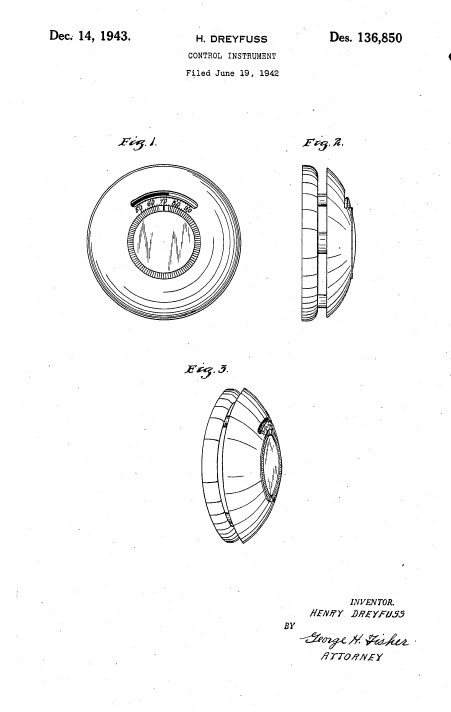

Henry Dreyfuss, Honeywell Thermostat Patent D-136,850

At the 1972 memorial service for Henry and Doris Dreyfuss, George Nelson said:

Many, many things that we see in our houses and our offices that Henry had something to do with have stood up very, very well. Even that almost invisible little thermostat you see everywhere. It's quite hard after ten years to figure out how you would do that any better.Fadell, to his credit, didn't. Or, he realized that roundness was again differentiating, especially when coupled with a sustainability agenda. Since Dreyfuss's lessons had been lost, he might as well rediscover them. The tagline for the Nest is that it is a learning thermostat: it will learn from your heating patterns, and save you money by not heating when it doesn't have to. The circular face becomes a symbol of simplicity, recycling, the lifecycle.

The Nest, therefore, is round. It has a brushed-steel case that should blend with most decor, and a black circular face that will not, unless your decor is mid-1990s bachelor pad. It comes with a level and screwdriver to help you install it straight (though that matters less, as Dreyfuss realized, than for the box thermostats), as well as a baseplate to cover the old box's tracks. To change the temperature, "Just turn the ring." So far, so Dreyfuss.

Since the center of the circle is an LED screen, there's no need for arrows; instead, the Nest's tick marks light up as you turn, showing the difference between actual and desired temperature. The central read-out then tells you how long it will take to get there. After a week of manual tuning, the Nest will remember your schedule, firing up the boiler at 6 a.m., shutting it down when you leave at 9 a.m., warming the baseboards at 6 p.m., and so on. No fiddling with tiny buttons! No manual! A green leaf (ah, the universal symbol of virtue) appears when you set your thermostat low enough to save energy (just put on a sweater!). Motion sensors pick up when there's no movement in the house for two hours, and shut the whole thing down until you reappear. So far, so good.

But then I read, in Manjoo's review, that after the Nest had learned his schedule, he tried to turn it up, and it didn't respond. He doesn't say this, but I have to assume he went over to the Nest and turned the ring and nothing happened. So he had to go online and manually adjust the learned schedule. Pogue had the opposite experience, finding the Nest's software on the Nest's tiny thermostat screen easier to use than the online options. (Takeaway: it's still buggy. But neither really reviewed the online interaction design. The video tour shows someone tap-tapping on their iPhone to raise the temperature, despite the representation of the round, which seems like a design fail.)

Either way, once you've used the ring for a week, you should almost never have to touch it again. The Nest becomes a glorified motion sensor, with a nice big temperature reading, rendering the ring obsolete. Because the Nest thermostat isn't just a thermostat. It's an app. You can control it from your computer, or remotely from an iPhone or iPad. You can chart your progress to energy efficiency. You can control the temperature of your house (like your locks, and your stereo, and your gararge door) from anywhere. Which makes the Nest, as industrial design object, possibly beside the point. Except for marketing.

Is the Nest really an heir to the Round? Or is it merely a decorative object (that leaf!) whose real functionality has been off-loaded to the cloud, where it is business as usual. This bothers me, partly because it seems like you can get easily-programmable functionality under the nouveau-Dreyfuss hood without an app. And second, why isn't this just an app? People are paying $250 for the pleasure of something better looking on their wall, but there's no real need, and little long term purpose, for it to be round. The Honeywell Round was easier to use than the competition because of its hardware, while the Nest is easier to use than the competition because of its software. The really sustainable move would be software for all the programmable thermostats, not a proprietary system for design geeks. Can there be a Linux of HVAC? Maybe the truly iconic 21st-century thermostat would be an invisible one.

Comments [4]

alignment is probably more important in round objects than all others. once there is any text, graphic or any marking at all some directionality is implied.

misaligned rectangluar is so common place it is could be ubiquitous.

mis aligned round just looks plain incompetent. think of the also once common clock.

12.17.11

10:09

12.30.11

06:17

My mother built an addition that had the thermostat. The older part of the house had a cast metal, vertical box with a notched wheel poking out of the top that I liked a lot more. I liked the heft of the metal, the ribbing on the case and the feel of turning the notched wheel. The font for the numbers was nice too.

Obviously at a time when neo-60s is so big many will disagree. Chacun à son goût. I suspect that most of the people who like neo-60s architecture weren't alive when it was built. They miss the original gray flannel suit / IBM associations.

01.03.12

05:28

Mr. Massengale is correct about the fonts and size of the numbers on the original T-86. Alvin Tilley, a man of few words, opened one of his many reference books to show me how the original iteration had been critiqued by the human factors community for just these shortcomings. They became sustantially larger and more legible when "See Deep" plastic allowed a bigger "lens" for the dial.

But the main thing people should know about the Round is that when it came onto the market it simultaneously made most of its competitors obsolete AND undercut them all on price. Game over.

The fact that its removable ring could be painted to match your decor (almost nobody did this in the end) allowed the marketing department to sell management on 4-color ads in the major magazines (e.g. Saturday Evening Post). It was a huge hit.

Henry was once bemoaning the fact that "industrial design is just there to make rich people richer" to Stanley Marcus, who said to him, "Henry, you're in every house in America with the telephones and the thermostats."

Carl Kronmiller was lead engineer on the project and deserves at least equal credit with Henry Dreyfuss (and Julian Everett, who was the partner who actually oversaw the account and did many of the drawings himself. Trained as an architect, he should also be credited with the round Mosler safe at 510 Fifth Avenue...if it's still there).

01.05.12

08:10