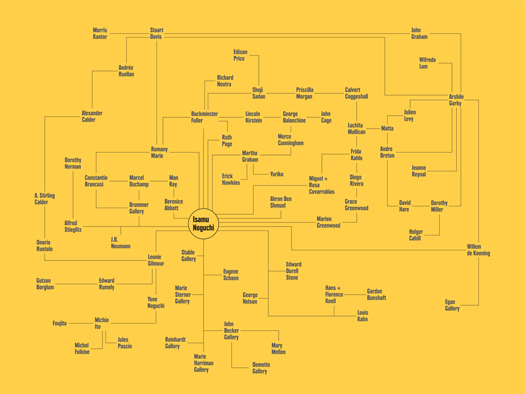

On the wall at the Noguchi Museum's excellent new show, On Becoming an Artist: Isamu Noguchi and His Contemporaries, 1922-1960, is the flow chart above, reducing the artistic collaborations of a lifetime to a series of black lines. Charts like these are a bit of an obsession for mid-century design historians. There's one on the cover of Gordon Bruce's monograph on Eliot Noyes. Metropolis published this chart of Philip Johnson's many tentacles. Charles Eames even doodled one of his own. They are a quick and pseudo-scientific way to make an important point: the worlds of art, design and architecture at mid-century were small, and all the players closely entwined. We think of Noguchi as a sort of Zen genius, Gordon Bunshaft as a pushy corporate pawn, but the two worked together for years. Bunshaft may have given Noguchi his best commissions, like Connecticut General, below, and even had a Noguchi at his lovely Hamptons house (you know, the one Martha Stewart tore down). Our idea of the personalities breaks down in the face of data.

"The Family," Connecticut General Life Insurance Co., Bloomfield, CT, 1956 © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

But the flip side of this reduction, the crashing together of John Cage and Frida Kahlo in close proximity, is a loss of context. The exhibition and its accompanying catalog by curator Amy Wolf periodize Noguchi's collaborations. We see him spending a year in Paris, 1926-1927, in the company of Constantin Brancusi (the sublime 1920 "Sculpture for the Blind" is in the show), Alexander Calder and (my favorite) Stuart Davis, the latter before he became pop. We see Noguchi's portrait heads, particularly the mirror-like noggin of mentor Buckminster Fuller, in the context of this odd all-but-abstract period in art. Noguchi's design period would come much later, in the 1950s, when he worked for rivals George Nelson at Herman Miller and Florence Knoll at Knoll, creating those charming rocking stools and the biomorphic coffee table. One of my favorite items in the show is the advertisement for his Prismatic Table, below, created for an Alcoa-sponsored program showing the ends of aluminum.

Prismatic Table ad, The New Yorker, May 11, 1957 (via Dinosaurs and Robots).

Its specified pastel colors are a rebuke to the reissue, made more "modern" in red, white and black. Despite the table's geometric shape and modular concept, the Jordan almond-colored enamels make it clear this is a domestic object. It has that hint of bad taste that's so hard to find, and made me think I should consider some robin's egg blue for my living room.

The exhibition's last room was the one of most interest to me, Noguchi's collaborations with architects. These include his wonderful playgrounds with Louis Kahn, the gardens for Bunshaft buildings and (new to me) an unbuilt pool for Richard Neutra's 1935 Josef von Sternberg house, a curve that would have echoed the house's canonical metallic prow. You have to go to Atlanta's Piedmont Park to see Noguchi's play ideas in action.

Noguchi and model, von Sternberg pool, 1935 © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

A final note about flow charts. Don't think that I didn't notice this one suffers from some graphic problems. First of all: What's a line? Friendship, collaboration, money? Second, is there a hierarchy of time and space? Third, is there a larger entity responsible for the connection, like MoMA (in the case of Edward Durell Stone and A. Conger Goodyear)? The first chapter of my yet-to-be-published book, "There's No Place Like Work," describes in narrative form the larger context for the connections of Noguchi, Noyes, Johnson and Eames. (I'm still waiting for some data-hungry designer to volunteer to make it into a fold-out org chart for me.) What I don't do is place one man (or, in the Eames case, one couple) at the center. Such charts repeat the problems of the monograph, by looking at a period through the lens of a singular genius. Rather, I look at the points of maximum contact, and make them the foci of the network. Institutions like MoMA, Lincoln Center, Aspen. Schools like Harvard, Cranbrook, MIT. Corporations like IBM, which employed all of the designers mentioned above but for Johnson.

So don't just read the chart, go to Queens and see the show. And the whole time, be thinking of all the other wonderful connections you can make. The network is not a closed entity, but an endlessly expandable web.

Comments [1]

Florence Knoll Bassett, or "Shu", as she was known to her close friends, considered Noguchi to be a close friend. The two worked together not only on the stools for the Alcoa building but also on a park project in Miami towards the end of Noguchi's life.

04.20.11

12:33